Hemangiomas of the spinal cord and epidural space of the spinal canal

- Understanding Hemangiomas of the Spinal Cord and Epidural Space

- Spinal Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs)

- Diagnosis of Spinal Vascular Malformations

- Cavernous Hemangiomas (Cavernomas) of the Spinal Cord and Epidural Space

- Treatment Strategies for Spinal Hemangiomas and AVMs

- Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Cord Lesions

- Complications and Prognosis

- When to Consult a Neurosurgeon or Neurologist

- References

Understanding Hemangiomas of the Spinal Cord and Epidural Space

Hemangiomas are benign vascular malformations composed of abnormal blood vessels. When they occur within the spinal canal, they can involve the epidural space (the space outside the dura mater surrounding the spinal cord) or the spinal cord itself (intramedullary lesions). These lesions can lead to neurological symptoms through compression of neural structures, hemorrhage, or vascular steal phenomena.

Classification of Spinal Epidural Hemangiomas

Several types of hemangiomas can be observed in the epidural space of the spinal canal. These are generally classified according to the predominant type of vascular bed involved:

- Cavernous Hemangiomas (Cavernomas): Composed of dilated, thin-walled sinusoidal vascular channels, often described as resembling a "mulberry." These are the most common type of symptomatic vascular malformation found in the epidural space.

- Capillary Hemangiomas: Made up of a proliferation of small, capillary-sized vessels.

- Arteriovenous Hemangiomas (or Arteriovenous Malformations - AVMs): Consist of a direct connection between arteries and veins without an intervening capillary bed, forming a nidus of abnormal vessels. These are more accurately termed AVMs.

- Venous Hemangiomas (or Venous Angiomas / Developmental Venous Anomalies - DVAs): Composed of anomalous veins draining normal neural tissue. These are generally considered benign developmental variants and are rarely symptomatic unless associated with a cavernoma or hemorrhage.

While the most common type of hemangioma specifically arising within the epidural space of the spinal canal is the cavernous type, information in modern literature regarding pure capillary, arteriovenous, and venous hemangiomas *confined solely to the epidural space* is relatively scarce as distinct entities from those involving the spinal cord or dura. Arteriovenous and venous malformations are often described as involving a network of vessels which can appear as small cystic or serpiginous masses on imaging, whereas cavernous and capillary types typically appear as more solid, though highly vascularized, masses.

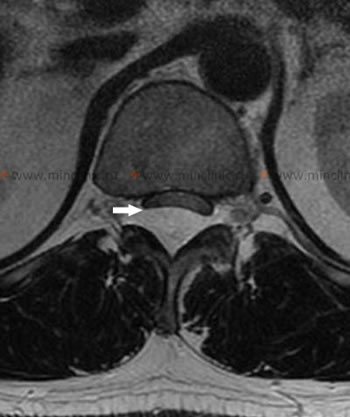

This MRI of the lumbar spinal cord (sagittal view, without contrast) at the level of the Th12-L1 vertebrae demonstrates an epidural cavernous hemangioma (indicated by an arrow) located posteriorly, which is displacing and compressing the spinal cord anteriorly.

Spinal Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs)

Spinal Arteriovenous Malformations (AVMs), also referred to as spinal angiomas or sometimes broadly under "hemangiomas" in older literature, represent some of the most challenging pathological processes to diagnose affecting the spinal vessels (arteries and veins). They consist of an abnormal tangle of blood vessels where arteries connect directly to veins, bypassing the normal capillary network. This results in high-flow, low-resistance shunting of blood.

Neurological Manifestations (Symptoms and Syndromes) of Spinal AVMs

The clinical manifestations of spinal AVMs are highly varied in patients, depending on the AVM's location, size, type of shunt, presence of hemorrhage, and secondary effects like venous hypertension or vascular steal. Neurological symptoms and syndromes can mimic other spinal cord disorders, including:

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Transverse Myelitis

- Spinal Cord Infarction (Spinal Stroke)

- Neoplastic Spinal Cord Compression

Spinal AVMs are more frequently localized in the lower thoracic and lumbar regions of the spinal cord. This type of spinal cord vascular lesion is more often diagnosed in middle-aged men. In most cases, spinal AVMs begin to manifest as an incomplete, progressively worsening spinal cord injury (myelopathy). This syndrome can present sporadically and subacutely, resembling multiple sclerosis, and is often accompanied by symptoms of bilateral involvement of the corticospinal tracts (motor weakness, spasticity), spinothalamic tracts (pain and temperature sensory loss), and posterior columns (vibration and proprioception loss) in various combinations. A significant number of patients may develop paraparesis and become unable to walk over several years.

Pathophysiology and Clinical Course

Approximately 30% of patients with spinal AVMs may experience a sudden onset of acute transverse myelopathy syndrome due to hemorrhage (bleeding) from the AVM into the spinal cord (hematomyelia) or subarachnoid space (spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage). This acute presentation neurologically resembles acute myelitis. Other patients may experience several severe exacerbations with partial recovery in between.

Around 50% of patients with spinal AVMs complain of back pain or radicular pain (pain radiating along a nerve root). These pains can sometimes cause intermittent neurogenic claudication (leg pain, numbness, or weakness provoked by walking and relieved by rest), similar to symptoms seen in lumbar spinal stenosis. Some patients describe an acute onset of their illness with sharp, localized back pain, often signaling a hemorrhage.

The development of myelopathy caused by non-bleeding spinal AVMs can be due to several mechanisms, including a chronic, progressive, non-inflammatory necrotic process (necrotizing myelopathy, also known as Foix-Alajouanine syndrome in some dural AVMs) secondary to spinal cord ischemia or venous hypertension. Ischemia can result from a "vascular steal" phenomenon, where blood is shunted away from normal spinal cord tissue towards the low-resistance AVM. Venous hypertension occurs due to impaired venous drainage from the spinal cord because of the high-flow shunt. Necrotizing myelopathy in AVMs is accompanied by a syndrome of progressive intramedullary spinal cord injury, leading to worsening neurological deficits.

This MRI of the spinal cord demonstrates an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) located at the level of the conus medullaris (the terminal end of the spinal cord), as indicated by the arrows. Such lesions can have multiple arterial feeders.

Diagnosis of Spinal Vascular Malformations

Clinical Evaluation

Changes in the intensity of pain and the severity of neurological symptoms that fluctuate with exercise, specific body positions (e.g., symptoms worsening when supine or with Valsalva maneuvers), or during menstruation in women, can be suggestive clues in diagnosing spinal vascular malformations. Auscultation (listening with a stethoscope) over the spine in the area of a suspected AVM may rarely reveal a vascular bruit (murmur), especially with high-flow lesions. An attempt should be made to detect such bruits both with the patient at rest and after physical exertion.

Instrumental and Laboratory Diagnostics

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis: In most patients with spinal AVMs, especially after a hemorrhage, the protein content in the CSF may be increased (xanthochromia and red blood cells if recent bleed). Pleocytosis (increased white blood cell count) is also possible. Lumbar puncture (LP) is performed to measure CSF pressure, assess the patency of the subarachnoid space, and determine the color, transparency, and cellular/chemical composition of the CSF.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI of the spinal cord is the initial imaging modality of choice. It can reveal signs of hematomyelia, spinal cord edema, dilated perimedullary or intramedullary vessels (flow voids), and chronic changes like cord atrophy or myelomalacia. Contrast-enhanced MRI can better delineate some vascular lesions.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Angiography: Myelography combined with CT angiography using contrast can visualize vascular lesions in many cases. The study is typically carried out with the patient lying supine.

- Selective Spinal Angiography: This is the gold standard for diagnosing and characterizing spinal AVMs. It allows precise delineation of the AVM's anatomical structure, including its feeding arteries, the nidus, and draining veins. The procedure for selective spinal angiography is complex and requires significant expertise from the interventional neuroradiologist or neurosurgeon to perform safely and effectively.

A lumbar puncture (LP), or spinal tap, is performed to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Analysis of CSF helps measure pressure, study the patency of the spinal subarachnoid space, and determine its color, transparency, and cellular/chemical composition, aiding in the diagnosis of various spinal cord diseases.

Cavernous Hemangiomas (Cavernomas) of the Spinal Cord and Epidural Space

Cavernous hemangiomas, also known as cavernomas or cavernous malformations, are well-circumscribed vascular lesions composed of dilated, thin-walled sinusoidal blood vessels packed closely together without significant intervening neural tissue. They lack large feeding arteries or draining veins characteristic of AVMs, making them low-flow lesions.

Purely epidural cavernous hemangiomas of the spinal canal are rare, accounting for approximately 4% of all primary epidural spinal tumors and about 12% of all spinal hemangiomas (this figure likely includes intramedullary and vertebral hemangiomas as well). A definitive diagnosis of epidural cavernous hemangioma in a patient is often made after histological examination of surgically obtained material. The tumor is not malignant in nature, but due to its volume and potential for growth or hemorrhage, it can cause significant secondary problems by compressing the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Clinical Presentation and MRI Characteristics

Depending on the location (level and relation to the spinal cord) of an epidural cavernous hemangioma, patients may complain of:

- Back pain (often localized or radicular).

- Progressive weakness and numbness in the arms or legs (myelopathy or radiculopathy).

- Bladder or bowel dysfunction (less common than pain or motor/sensory deficits, but can occur with significant compression).

Cavernous hemangiomas have a known tendency to bleed (hemorrhage). A large or acute hemorrhage can cause sudden onset or rapid worsening of neurological symptoms due to acute spinal cord compression. Patients may also experience chronic, progressive neurological symptoms if the cavernous hemangioma grows slowly and is not accompanied by acute bleeding.

MRI of the spinal cord is the best diagnostic method for visualizing epidural cavernous hemangiomas. Classic MRI findings include:

- A well-defined mass located in the epidural space, often indenting or displacing the spinal cord. It can also spread into adjacent neural foramina where nerve roots exit.

- T1-weighted images (T1WI): The mass typically shows a signal intensity similar to adjacent intervertebral discs (isointense) or may have foci of hyperintense signal (due to methemoglobin from previous small bleeds).

- T2-weighted images (T2WI): Most often show heterogeneous or homogeneous signal amplification (hyperintensity). A characteristic "popcorn" or "mulberry" appearance with a hemosiderin rim (low signal intensity due to old blood products) is classic for cavernomas in the brain and can sometimes be seen in spinal lesions, especially intramedullary ones. Low signal on T2WI is also common.

- Post-contrast images (T1WI with gadolinium): Usually produce noticeable, often heterogeneous, signal enhancement within the cavernous hemangioma.

Some cavernous hemangiomas on MRI may also have connections to the dura mater, presenting as a "dural tail" sign (thin thickening of the dura adjacent to a wide-based hemangioma mass). If the cavernous hemangioma is located in the lateral part of the epidural space, it can lead to the expansion of an intervertebral foramen.

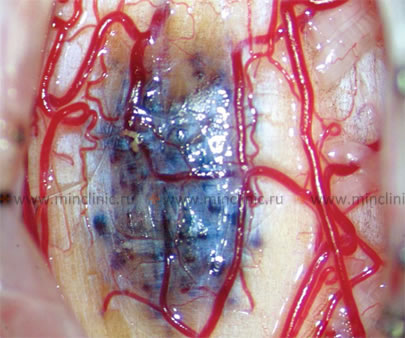

This MRI scan of the lumbar spinal cord, in a transverse (axial) section at the Th12-L1 vertebral level, reveals an epidural cavernous hemangioma (indicated by an arrow) which is pushing the spinal cord anteriorly.

This MRI of the lumbar spinal cord at the Th12-L1 vertebral level, after the administration of a contrast agent, demonstrates an epidural cavernous hemangioma (indicated by an arrow) which is enhancing and displacing the spinal cord anteriorly.

Differential Diagnosis of Epidural Cavernous Hemangioma

The differential diagnosis for an enhancing epidural mass includes:

- Meningioma

- Lymphoma

- Schwannoma (Nerve Sheath Tumor)

- Angiolipoma

- Herniated Intervertebral Disc (especially if sequestered or migrated)

- Synovial Cyst (from facet joint)

- Granulomatous Infection (e.g., tuberculosis)

- True Epidural Hematoma (often related to trauma, surgery, or coagulopathy)

- Extramedullary Hematopoiesis (in patients with certain hematological disorders like sickle cell disease or thalassemia; often associated with characteristic bone marrow changes in adjacent vertebrae on MRI).

A combination of the patient's medical history, neurological examination findings, laboratory results, and specific MRI characteristics helps to narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, a history of trauma, spinal surgery, or coagulopathy would raise suspicion for a true epidural hematoma. Pain exacerbated by lifting or physical exertion might suggest a herniated disc. Fever, neck muscle tension, and tenderness on palpation of spinous processes are more indicative of an epidural infection (bacterial epiduritis).

Treatment Considerations: Intramedullary vs. Extramedullary Cavernous Hemangiomas

Intramedullary cavernous hemangiomas (located within the substance of the spinal cord) are more common than purely epidural (extramedullary) ones. Surgical removal of any symptomatic hemangioma is generally recommended if other less invasive treatment methods like embolization (for AVMs or highly vascular lesions) or radiation therapy (radiosurgery for some cavernomas) are ineffective or not suitable. The risk of bleeding from a spinal cavernoma is estimated to be around 1.4% to 4.5% per year per lesion. If a patient has already experienced one hemorrhage from a cavernoma, the risk of re-bleeding is significantly higher, estimated at up to 66% per year in some series.

Even in the absence of acute bleeding, both intramedullary and extramedullary cavernous hemangiomas can cause a progressive deterioration in the clinical picture. This is often due to the gradual increase in the volume of the hemangioma itself (from microhemorrhages, thrombosis, or slow growth), which is observed in most cases, or due to repeated small, subclinical bleeds leading to gliosis and hemosiderin deposition.

In the postoperative period, the best clinical results are generally obtained in patients with purely extramedullary (e.g., epidural) localization of cavernous hemangiomas, compared to intramedullary ones. Extramedullary cavernous hemangiomas lie outside the spinal cord and can often be removed while leaving the spinal cord itself intact, leading to a higher rate of neurological improvement (e.g., reported around 90% improvement after surgery in some series). Intramedullary cavernous hemangiomas grow within the spinal cord tissue, which must be carefully dissected (myelotomy) to allow access to the tumor. This carries a higher risk of surgical morbidity, and the rate of neurological improvement after surgery for intramedullary lesions is typically lower (e.g., around 62% in some series), with a greater chance of new or worsened deficits postoperatively, though complete resection can prevent future hemorrhages.

This image demonstrates the endovascular procedure of embolization for an extradural arteriovenous malformation (AVM) of the spinal cord. The procedure is performed under X-ray (fluoroscopic) control with the use of contrast agent to visualize the vessels and guide the delivery of embolic material.

Treatment Strategies for Spinal Hemangiomas and AVMs

The management of spinal vascular malformations is complex and depends on the type of lesion, its location, size, clinical presentation (symptomatic vs. asymptomatic, presence of hemorrhage), and the patient's overall condition. A multidisciplinary approach involving neurosurgeons, interventional neuroradiologists, and neurologists is often required.

- Observation: Asymptomatic, incidentally discovered cavernomas or small, stable AVMs without prior hemorrhage may be managed conservatively with regular clinical and MRI follow-up.

- Surgical Resection: This is the primary treatment for symptomatic cavernous hemangiomas (both intramedullary and epidural) and for many accessible AVMs, especially those that have bled or are causing progressive neurological deficits. The goal is complete microsurgical excision of the lesion while preserving neurological function. Intraoperative monitoring of spinal cord function (e.g., SSEPs, MEPs) is often used.

- Endovascular Embolization: Primarily used for spinal AVMs (especially dural arteriovenous fistulas or high-flow intramedullary AVMs). Embolization aims to occlude the feeding arteries or the shunt itself using various embolic materials (e.g., glue, particles, coils) delivered via catheters. It can be used as a standalone treatment, preoperatively to reduce bleeding during surgery, or palliatively. It is generally not effective for cavernomas as they lack distinct feeding arteries.

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS): An option for small, well-defined intramedullary cavernomas or residual/inoperable AVMs that are not amenable to surgery or embolization. SRS delivers a highly focused dose of radiation to the lesion, aiming to induce thrombosis and obliteration over time. Its role in spinal vascular malformations is still evolving and is generally considered for lesions with a higher risk of surgical morbidity.

- Medical Management: There are no specific medical therapies to shrink or eliminate these vascular lesions. Management focuses on symptomatic relief (e.g., pain medication, management of spasticity) and supportive care during and after interventions. Anticoagulation is generally contraindicated if there is a history of hemorrhage.

Differential Diagnosis of Spinal Cord Lesions

Spinal hemangiomas and AVMs must be differentiated from other conditions that can cause spinal cord compression or myelopathy:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features on MRI / Clinical |

|---|---|

| Spinal Cavernous Hemangioma (Cavernoma) | Well-circumscribed, "popcorn" or "mulberry" appearance, hemosiderin rim (low signal on T2/GRE). Heterogeneous signal on T1/T2. Variable enhancement. History of acute or subacute deficits from bleeds. |

| Spinal Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM) | Serpiginous flow voids (dilated vessels) on T2WI, prominent enhancement of nidus/draining veins. Angiography confirms. Can cause progressive myelopathy (Foix-Alajouanine) or acute hemorrhage. |

| Spinal Epidural Hematoma | Often history of trauma, coagulopathy, or spinal procedure. Signal characteristics on MRI vary with age of blood. Biconvex epidural collection. |

| Herniated Intervertebral Disc | Disc material extending beyond confines of disc space, compressing cord or nerve roots. Signal similar to parent disc. |

| Spinal Tumors (e.g., Meningioma, Schwannoma, Ependymoma, Astrocytoma, Metastasis) | Solid or cystic masses with characteristic locations (intradural-extramedullary, intramedullary, extradural). Specific enhancement patterns and signal characteristics. Often progressive symptoms. |

| Spinal Epidural Abscess | Fever, severe back pain, rapidly progressive neurological deficits. MRI shows epidural collection with rim enhancement, often associated discitis/osteomyelitis. Diffusion restriction. |

| Transverse Myelitis / Multiple Sclerosis | Intrinsic cord lesion(s) with T2 hyperintensity, often enhancing. Clinical history of relapses/remissions or acute onset. CSF may show oligoclonal bands. |

| Angiolipoma (Epidural) | Epidural mass containing both vascular and fatty components. Fat will be hyperintense on T1WI and suppress with fat-saturation sequences. |

Complications and Prognosis

Potential complications of spinal hemangiomas and AVMs include:

- Hemorrhage: Leading to acute neurological deficits (hematomyelia, spinal subarachnoid hemorrhage, epidural hematoma).

- Progressive Myelopathy: Due to mass effect, vascular steal, venous hypertension, or repeated microhemorrhages.

- Permanent Neurological Deficits: Weakness, paralysis, sensory loss, bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- Chronic Pain Syndromes.

- Complications related to treatment (e.g., surgical morbidity, post-embolization ischemia, radiation myelopathy).

The prognosis is highly variable. Asymptomatic, stable lesions may have a good prognosis. Symptomatic lesions, especially those that have bled or are causing progressive deficits, carry a more guarded prognosis. Outcomes depend on the type and location of the malformation, the severity of neurological deficits at presentation, and the success and risks of treatment. Extramedullary cavernous hemangiomas generally have better surgical outcomes than intramedullary ones.

When to Consult a Neurosurgeon or Neurologist

Urgent consultation with a neurosurgeon and/or neurologist specializing in spinal disorders is necessary if an individual experiences:

- Sudden onset of severe back pain associated with weakness, numbness, or bowel/bladder dysfunction (suggestive of acute hemorrhage or cord compression).

- Progressive neurological symptoms such as worsening weakness, sensory changes, or gait disturbance.

- Symptoms suggestive of myelopathy or radiculopathy that cannot be explained by common degenerative conditions.

- Incidental finding of a spinal vascular malformation on imaging, even if asymptomatic, to discuss management options and monitoring.

Early diagnosis and specialized management are crucial for optimizing outcomes and preventing irreversible neurological damage from these complex vascular lesions.

References

- Anson JA, Spetzler RF. Classification of spinal arteriovenous malformations and implications for treatment. BNI Quarterly. 1992;8(2):2-8.

- Rosenblum B, Oldfield EH, Doppman JL, Di Chiro G. Spinal arteriovenous malformations: a comparison of dural arteriovenous fistulas and intradural AVM's in 81 patients. J Neurosurg. 1987 Jun;66(6):795-802.

- McCormick PC, Michelsen WJ, Post KD, et al. Cavernous malformations of the spinal cord. Neurosurgery. 1988;23(4):459-463.

- Zevgaridis D, Medele RJ, Hamburger C, Steiger HJ, Reulen HJ. Cavernous haemangiomas of the spinal cord. A review of 117 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1999;141(3):237-45.

- Bao YH, Ling F. Classification and therapeutic modalities of spinal vascular malformations. Neurosurg Rev. 2000;23(1):1-14.

- Lee TT, Gromelski EB, Bowen J, et al. Outcome after surgical treatment of intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Neurosurgery. 2000 May;46(5):1094-101; discussion 1101-2. (Context for intramedullary lesions)

- Benes V 3rd, Barsa P, Benes V Jr. Spinal cavernomas. Spinal Cord. 2002 Aug;40(8):397-402.

- Cohen-Gadol AA,EENBERG JK, YONG WH, et al. Spinal cavernous malformations: a review of the Mayo Clinic experience. J Neurosurg Spine. 2003 Jan;98(1):1-6.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome