Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Lumbar Spine

- Understanding MRI of the Lumbar Spine (Lumbosacral Spine)

- Clinical Indications for Lumbar Spine MRI

- MRI Techniques and Image Reconstruction

- Patient Preparation and Procedure

- Advantages and Limitations of Lumbar Spine MRI

- Comparison with Other Spinal Imaging Modalities

- Interpreting Lumbar Spine MRI: Examples

- The Role of Lumbar MRI in Diagnosis and Management

- References

Understanding Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Lumbar Spine (Lumbosacral Spine)

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine (often including the lumbosacral region) is a highly advanced, non-invasive diagnostic imaging technique that has become a cornerstone in modern neuroradiology and spine care. It provides detailed cross-sectional images of the lumbar vertebrae (lower back bones), intervertebral discs, spinal cord (conus medullaris and cauda equina at this level), nerve roots, and surrounding soft tissues without the use of ionizing radiation.

Diagnostic Capabilities and Principles

Utilizing strong magnetic fields, radiofrequency pulses, and sophisticated computer algorithms, lumbar spine MRI allows physicians to meticulously investigate structural abnormalities and pathological changes. Beyond mere anatomy, MRI can also provide insights into certain physicochemical and pathophysiological processes affecting the entire lumbar spine or its individual components, such as inflammation, edema, or ischemia within the spinal cord or nerve roots.

Video explaining the lumbar spine MRI procedure and what to expect.

Advanced Imaging: Functional Studies and MRA

MRI of the lumbosacral spine also makes it possible to conduct certain types of functional studies of the spinal cord (e.g., diffusion tensor imaging for white matter tracts, though less common at this level than in the brain or cervical cord) and to perform Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) of the arteries supplying the spinal cord and surrounding structures. MRA of spinal arteries is a specialized technique that typically does not require direct arterial puncture, unlike conventional selective angiography, offering a non-invasive way to assess vascular anatomy and pathology.

Assessing Intervertebral Discs and Joints

Using MRI of the lumbosacral spine, physicians can reliably assess the state of various structures in patients presenting with back pain (particularly in the lower back or with radiation to the leg - sciatica). Key structures evaluated include:

- Intervertebral Discs: MRI is excellent for detecting disc degeneration (discitis if inflammatory), disc herniations (extrusion, sequestration), and protrusions (bulges), and their impact on nerve roots or the a cord/cauda equina.

- Facet Joints and Sacroiliac Joints: MRI can reveal inflammation (sacroiliitis), degenerative changes (spondyloarthrosis), bone spurs (spondylosis), ankylosing spondylitis, and other arthropathies affecting these joints.

In most cases of lumbar spine MRI, there is no need for invasive procedures like lumbar puncture (which was more widely used by neurologists and neurosurgeons in the past for diagnosing certain traumatic lesions and infectious diseases of the spine and brain, e.g., by analyzing cerebrospinal fluid or for myelography).

Detecting Congenital Anomalies

MRI of the lumbosacral spine is also effective in revealing congenital anomalies in the development of the spine and spinal cord at the lumbar level. Such anomalies can be a source of back pain or neurological symptoms. Examples include:

- Spina Bifida: Incomplete closure of the vertebral arch (can be occulta or associated with meningocele/myelomeningocele).

- Sacralization: Fusion of the L5 vertebra to the sacrum.

- Lumbarization: Separation of the S1 segment from the sacrum, appearing as an L6 vertebra.

- Spondylolisthesis: Anterior or posterior slippage of one vertebra relative to another, which can be congenital (dysplastic) or acquired.

- Tethered cord syndrome.

- Diastematomyelia (split spinal cord).

Clinical Indications for Lumbar Spine MRI

An MRI examination of the lumbar spine may be prescribed in various clinical scenarios, including:

- Osteochondrosis of the lumbar spine presenting with chronic or acute back pain.

- Suspected disc protrusion or herniated disc of the lumbar spine, especially if causing radicular pain (sciatica) radiating to the leg(s).

- Evaluation for metastases of tumor cells at the level of the lumbar spine, particularly if associated with neurological deficits like paralysis or paresis of the lower extremity muscles, or disruption of pelvic organ function (bowel/bladder incontinence, sexual dysfunction).

- Detection and characterization of vascular lesions such as hemangiomas within the vertebral bodies, or vascular malformations (cavernous, capillary, arteriovenous malformations - AVM, venous angiomas) in the spinal cord or epidural space of the spinal canal.

- Diagnosis of spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal or neural foramina) causing neurogenic claudication or radiculopathy.

- Assessment of lumbar spine injuries, including vertebral fractures, dislocations, ligamentous injuries, or spinal instability.

- Investigation of inflammatory or infectious conditions like discitis, vertebral osteomyelitis, or epidural abscess.

- Evaluation of congenital anomalies of the lumbosacral spine.

- Assessment of post-operative changes and complications.

MRI Techniques and Image Reconstruction

MRI of the spine allows for the acquisition of a series of thin cross-sectional images in multiple planes (sagittal, axial, and sometimes coronal). These images can be used to create three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions of the investigated spinal segment. With MRI, it is possible to highlight the vasculature (using MRA sequences), visualize ligaments, assess the epidural space (important for conditions like epiduritis), and even delineate individual nerve trunks (cauda equina nerve roots) emerging from the spinal canal.

Such detailed reconstructions provide invaluable assistance to neurosurgeons and spine surgeons in planning operations and for subsequent postoperative monitoring and control.

Standard MRI protocols for the lumbar spine include:

- T1-Weighted Images (T1W): Provide good anatomical detail, especially of bone marrow and epidural fat.

- T2-Weighted Images (T2W): Excellent for visualizing fluid-filled structures like the CSF within the spinal canal and the hydration status of intervertebral discs. Pathologies like disc herniations, edema, inflammation, and tumors often appear bright.

- STIR (Short Tau Inversion Recovery) or Fat-Saturated T2W: Suppresses fat signal, making fluid, edema (e.g., in vertebral compression fractures, inflammation), and some tumors more conspicuous.

- Post-Contrast T1-Weighted Images (with fat suppression): Acquired after intravenous administration of a gadolinium-based contrast agent (e.g., Omniscan, though specific agents vary). Contrast is used to highlight areas of inflammation (e.g., discitis, epiduritis), infection (abscess), tumors, or to assess postoperative scarring versus recurrent disc herniation.

Patients may undergo MRI of the spine using high-field scanners (e.g., 3.0 T) for enhanced image quality. Weight restrictions (e.g., up to 200 kg) apply to most scanners.

Patient Preparation and Procedure

Preparation for a lumbar spine MRI is usually minimal:

- Screening: A safety questionnaire is completed to identify contraindications (e.g., pacemakers, certain metallic implants, severe claustrophobia, pregnancy).

- Metal Objects: All removable ferromagnetic items must be removed.

- Clothing: Patients typically change into a hospital gown.

- Fasting: Generally not required for a standard lumbar spine MRI without sedation. If IV contrast or sedation is planned, specific instructions will be given.

During the procedure, the patient lies supine (on their back) on the MRI table. A specialized surface coil may be placed over their lower back to improve image quality. The table then slides into the MRI scanner. The patient must remain very still during the scan, which typically lasts 20-45 minutes. Loud knocking sounds are produced; earplugs or headphones are provided.

Advantages and Limitations of Lumbar Spine MRI

Advantages:

- Excellent visualization of soft tissues: spinal cord, cauda equina, nerve roots, intervertebral discs, ligaments, epidural space.

- No ionizing radiation.

- Multiplanar imaging capability.

- Highly sensitive for detecting disc herniations, spinal stenosis, tumors, infections, inflammation, and spinal cord abnormalities.

- Can identify early degenerative changes before they are visible on X-ray.

Limitations:

- Less sensitive than CT for detecting acute cortical bone fractures or fine bony detail (though excellent for bone marrow edema/bruises and stress fractures).

- Longer scan times compared to CT, more susceptible to motion artifacts.

- Higher cost than X-ray or CT.

- Contraindicated in patients with certain incompatible metallic implants.

- Challenging for claustrophobic patients.

- MRI findings (e.g., degenerative disc disease, disc bulges) are very common in asymptomatic individuals, requiring careful correlation with clinical symptoms to determine significance.

Comparison with Other Spinal Imaging Modalities

| Modality | Principle | Radiation | Primary Strengths for Lumbar Spine | Primary Weaknesses for Lumbar Spine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lumbar Spine MRI | Magnetic fields, radio waves | No | Spinal cord (conus/cauda equina), nerve roots, discs, ligaments, soft tissues, tumors, infection/inflammation. | Longer scan, motion sensitive, less bone detail than CT, cost, MRI contraindications. |

| Lumbar Spine CT Scan | X-rays | Yes | Excellent bone detail (fractures, degenerative bony changes, stenosis), calcified discs/ligaments. Faster than MRI, good in acute trauma. | Radiation, poorer soft tissue/cord/nerve root detail than MRI. Iodinated contrast risks if used (e.g., for CTA or CT myelography). |

| Lumbar Spine X-ray | X-rays | Yes (lower than CT) | Initial assessment of alignment (flexion/extension for instability), fractures, gross degenerative changes, spondylolisthesis, scoliosis. Inexpensive. | Limited soft tissue/cord/disc/nerve root detail. Superimposition. Poor for subtle fractures or early degeneration. |

| CT Myelography | X-rays with intrathecal contrast | Yes | Detailed visualization of spinal canal, nerve roots, cord/cauda equina compression when MRI is contraindicated or inconclusive. Dynamic assessment possible. | Invasive (lumbar puncture), contrast risks, radiation. Largely replaced by MRI for most indications. |

| Discography | Contrast injection into disc, X-ray/CT | Yes | Assesses disc integrity and pain provocation (controversial). | Invasive, risk of discitis, pain. Limited role. |

Interpreting Lumbar Spine MRI: Examples

MRI is crucial for identifying pathologies leading to low back pain and radiculopathy.

Disc Pathologies (Herniation, Protrusion, Annular Rupture)

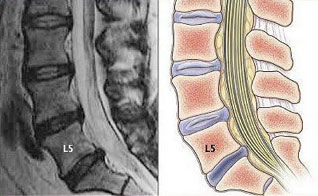

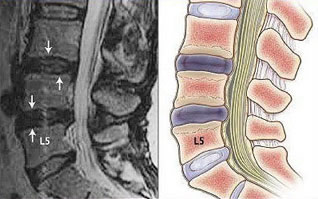

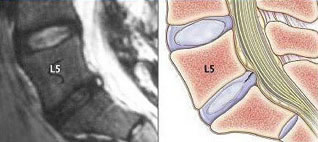

MRI accurately visualizes the intervertebral discs, identifying degeneration (loss of height, desiccation), bulges, protrusions (where the disc anulus remains intact but bulges), extrusions (where the nucleus pulposus breaks through the anulus but remains connected), and sequestrations (free fragments). The images provided show examples of L5-S1 disc herniation, L5-S1 disc protrusion, L3-L4 and L4-L5 disc protrusions, and a rupture of the anulus fibrosus at L5-S1, all of which can impinge on nerve roots causing sciatica or on the a cord/cauda equina causing more severe neurological symptoms.

Spinal Canal Stenosis by Tumor

The image illustrating thoracic stenosis due to a tumor demonstrates MRI's ability to show narrowing of the spinal canal and compression of neural elements. Similar findings can occur in the lumbar spine from tumors (primary or metastatic), severe disc herniations, or degenerative facet/ligamentum flavum hypertrophy.

Spinal Cord Arteriovenous Malformation (AVM)

The MRI of the conus medullaris shows an AVM, highlighting MRI's capability (often with MRA sequences or contrast) to detect vascular lesions within or around the spinal cord and cauda equina, which can cause pain, neurological deficits, or hemorrhage.

The Role of Lumbar MRI in Diagnosis and Management

Early and accurate diagnosis of lumbar spine diseases using MRI is essential for timely and appropriate treatment, whether conservative or surgical. The ability of MRI to simultaneously demonstrate:

- The spinal cord (conus medullaris) and cauda equina over a large extent without invasive procedures like myelography and without ionizing radiation.

- The precise location and size of tumors affecting the spine, spinal cord, nerve roots, or surrounding vascular structures.

- The condition of intervertebral discs, clearly identifying herniations and protrusions.

- The status of intervertebral (facet) joints and vertebral bodies for degenerative changes or fractures.

has positioned it as the foremost diagnostic tool for most diseases of the spinal cord and spine, often providing more definitive information than older methods like myelography or standard CT scans of the spine. This detailed information is critical for guiding treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

References

- Ross JS, Brant-Zawadzki M, Moore KR, et al. Diagnostic Imaging: Spine. 3rd ed. Amirsys Elsevier; 2015.

- Westbrook C, Roth C, Talbot J. MRI in Practice. 5th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2018. Chapter on Spinal Imaging.

- Atlas SW. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016.

- Modic MT, Masaryk TJ, Ross JS. Magnetic resonance imaging of the_spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 1989 Jul;27(4):887-901. (General reference to spine MRI)

- Fardon DF, Williams AL, Dohring EJ, et al. Lumbar disc nomenclature: version 2.0: Recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, the American Society of Spine Radiology and the American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine J. 2014 Nov 1;14(11):2525-45.

- American College of Radiology. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Low Back Pain. Last review date: 2021.

- Wilmink JT. CT and MRI of the spine and spinal cord. Saunders Ltd.; 2009.

- Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med. 2002 Oct 1;137(7):586-97.

See also

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) of the Cerebral Vessels

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Abdomen

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Brain

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Cervical Spine

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Hip Joint

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Knee Joint

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Lumbar Spine

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Pelvic Organs

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Pituitary Gland (Hypophysis)

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Shoulder Joint

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Thoracic Cavity Organs

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the Thoracic Spine

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Study Principle

- Whole-Body Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)