Vertebral spine CT scan

What is a Spine CT Scan?

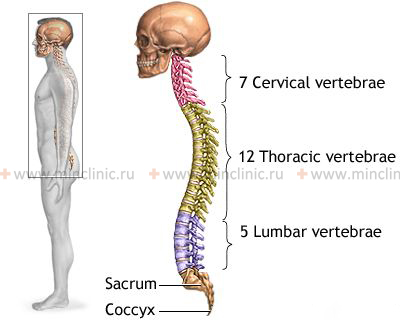

A Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the vertebral spine is an advanced imaging technique that uses X-rays and computer processing to create detailed cross-sectional images of the spinal column (cervical, thoracic, or lumbar regions). It provides excellent visualization of bone structures, and also shows intervertebral discs, ligaments, the spinal canal, nerve roots, and surrounding soft tissues.

Compared to conventional X-rays, spine CT offers superior detail, particularly for bone anatomy, subtle fractures, and degenerative changes. It is considered non-invasive (though contrast injection involves a needle if used) and is crucial in diagnosing various spinal conditions, including trauma, degenerative disc disease (osteochondrosis), herniated discs, and spinal stenosis (narrowing of the spinal canal or nerve root openings).

Spine CT clearly demonstrates elements causing narrowing of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina (openings where nerve roots exit), such as herniated discs, bone spurs (osteophytes), or thickened ligaments. It allows precise identification of their location, size, and relationship to adjacent nerves and the spinal cord.

A CT scan of the spine may be used to check the spine for conditions such as herniated discs, spinal stenosis (narrowing), scoliosis (curvature), traumatic injuries (fractures), tumors, congenital structural problems (like spina bifida), blood vessel issues, or infections.

How Spine CT Works

Like other CT scans, a spine CT involves the patient lying on a table that moves through the CT scanner's gantry. An X-ray tube rotates around the patient, taking multiple X-ray measurements from different angles. Detectors measure the X-rays passing through the body, and a computer reconstructs this data into detailed cross-sectional images (slices).

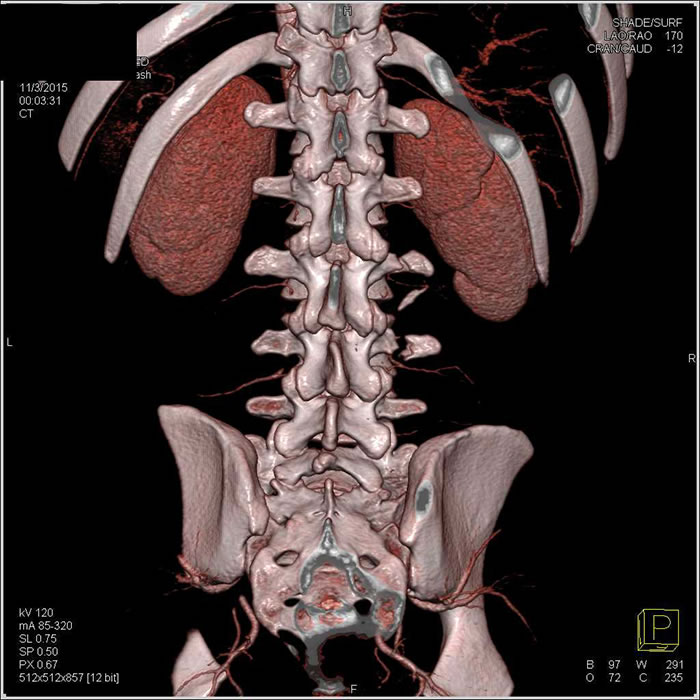

A key advantage of CT is the ability to perform multiplanar reconstructions (MPR). From the initial axial (cross-sectional) data, the computer can generate high-quality images in other planes – sagittal (side view), coronal (front view), and oblique (angled views). This comprehensive view is essential for accurately assessing spinal alignment, disc herniations, fractures, and foraminal narrowing.

Proper patient positioning is important. For lumbar spine scans aimed at evaluating disc herniation, lying supine (on the back), sometimes with a bolster under the knees to slightly flex the hips and flatten the lumbar curve (lordosis), can be helpful. The scanner gantry angle may be adjusted based on preliminary scout images to align the scan slices parallel to the plane of the intervertebral discs of interest, although modern volumetric scanning often makes precise angling less critical as reconstructions can be done afterwards.

Scan parameters, such as slice thickness (often around 3 mm for routine spine work, but can be thinner for detailed reconstructions) and scan pitch, are chosen by the radiologist or technologist to optimize image quality for the specific clinical question. A typical scan of one spinal segment might involve acquiring 8-12 main slices, which are then used for multiplanar reconstructions.

Indications for Spine CT Scan

Spine CT scans are indicated in various situations, including:

- Trauma Assessment: Detecting fractures (vertebral body, posterior elements, transverse/spinous processes), dislocations, and evaluating spinal stability after injury. CT is the primary modality for assessing bony injury.

- Evaluation of Degenerative Changes: Assessing osteoarthritis (facet joint arthropathy), bone spurs (osteophytes), degenerative disc disease, spondylosis, and spondylolisthesis (vertebral slippage).

- Diagnosis of Disc Herniation: Identifying disc protrusions or extrusions that may compress nerve roots or the spinal cord, especially when MRI is contraindicated or unavailable, or for specific pre-operative planning.

- Assessment of Spinal Stenosis: Measuring the dimensions of the central spinal canal and neural foramina to evaluate narrowing that can compress neural structures.

- Detection of Tumors: Identifying primary bone tumors, metastatic disease (cancer spread to the spine), or tumors involving the spinal canal or surrounding tissues (though MRI is often better for soft tissue tumors).

- Diagnosis of Infections: Evaluating for discitis (disc infection), osteomyelitis (bone infection), or epidural abscesses.

- Evaluation of Congenital Anomalies: Assessing structural abnormalities of the vertebrae or spinal canal present from birth.

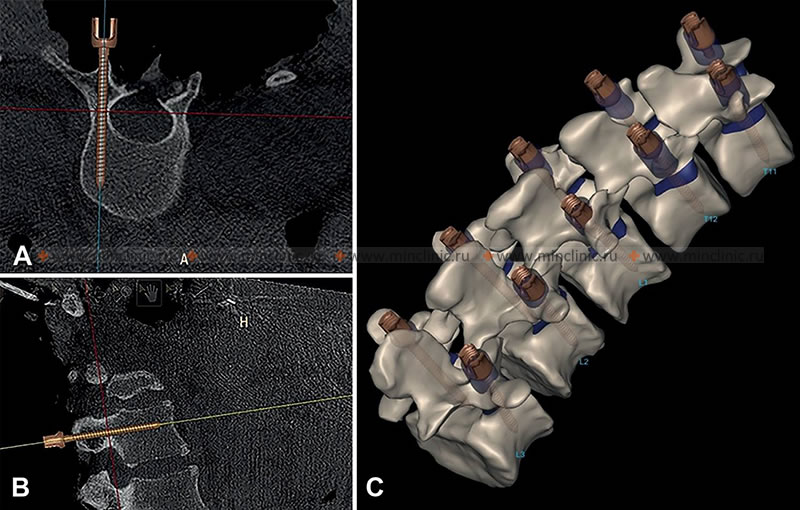

- Post-Operative Evaluation: Assessing surgical hardware placement (screws, rods, cages), fusion status, and potential complications like hardware loosening or pseudoarthrosis (failed fusion).

- Guidance for Procedures: Used to guide needle placement for biopsies, pain management injections (e.g., facet blocks, epidurals), or vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty.

- When MRI is Contraindicated: For patients with certain pacemakers, implants, or severe claustrophobia who cannot undergo MRI.

- Clarification of X-ray Findings: When plain X-rays are inconclusive or show abnormalities requiring more detailed evaluation.

- Symptoms of Radiculopathy or Myelopathy: Investigating nerve root compression (radiculopathy - e.g., sciatica) or spinal cord compression (myelopathy) when CT is deemed appropriate.

Common Spine CT Findings

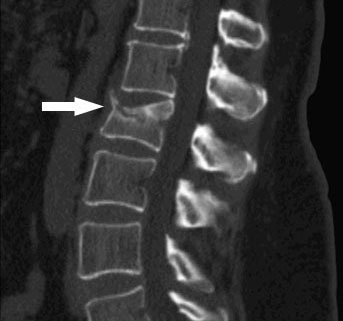

- Herniated Disc: Focal bulge or extrusion of intervertebral disc material beyond the normal confines of the disc space, potentially impinging on nerve roots or the thecal sac (containing the spinal cord/cauda equina). CT clearly shows the disc material, especially if calcified, and its relationship to bony structures.

- Spinal Stenosis: Narrowing of the central spinal canal or the neural foramina (where nerve roots exit). CT excels at showing bony causes of stenosis, such as facet joint hypertrophy (enlargement) and osteophytes (bone spurs), as well as contributions from disc bulging or ligament thickening (ligamentum flavum hypertrophy). Measurements of canal diameters can be made (e.g., absolute stenosis often defined as sagittal diameter <10 mm in the lumbar spine).

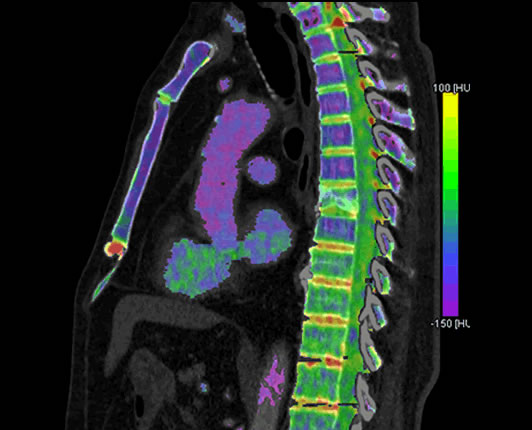

- Fractures: CT provides excellent detail of bone fractures, including their location, extent, displacement, and involvement of the spinal canal. Compression fractures, burst fractures, facet fractures, and fractures of the posterior elements are well visualized. Dual-energy CT can sometimes help differentiate acute (new) from chronic (old) compression fractures by detecting bone marrow edema.

- Degenerative Changes: Signs include disc space narrowing, osteophytes, facet joint arthritis (joint space narrowing, sclerosis, osteophytes), vacuum phenomenon (gas within the disc space), and endplate changes (sclerosis, Modic changes - though better seen on MRI).

- Spondylolisthesis: Forward or backward slippage of one vertebra relative to the one below it. CT can show associated pars interarticularis defects (spondylolysis) if present.

- Calcification: CT readily detects calcification within discs, ligaments (e.g., posterior longitudinal ligament - OPLL), or soft tissues.

- Bone Lesions: Can show destructive (lytic) or bone-forming (sclerotic) lesions suggestive of tumors (metastases, myeloma, primary bone tumors) or infection (osteomyelitis).

Relevant Spinal Anatomy on CT

Understanding basic spinal anatomy visible on CT is helpful:

- Spinal Cord: Contained within the spinal canal, typically ending around the L1-L2 vertebral level. Below this level, the canal contains the cauda equina (nerve roots). The spinal cord itself is better visualized with MRI, but its location and any compression by disc or bone can be inferred on CT.

- Nerve Roots: Exit the spinal canal through the intervertebral (neural) foramina. Their path can be affected by disc herniations (especially foraminal or far-lateral herniations) or foraminal stenosis caused by facet joint arthritis or osteophytes. Nerve roots generally exit *above* the pedicle of their corresponding vertebra (e.g., L4 root exits below the L4 pedicle).

- Intervertebral Disc: Normally has a density between 75-100 Hounsfield Units (HU). Degenerated discs may show decreased height, vacuum phenomenon (gas), or calcification.

- Vertebral Bone: Cancellous (spongy) bone density is typically around 170 ± 55 HU but decreases significantly in osteoporosis (can approach 0 HU) and increases in osteosclerosis (up to 500 HU or more).

- Ligaments: The posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) runs along the back of the vertebral bodies within the canal (normally < 2mm thick). The ligamentum flavum connects the laminae posteriorly (normally < 3-5 mm thick depending on level). Thickening or calcification of these ligaments can contribute to stenosis.

- Venous Plexuses: Epidural venous plexuses (like Batson's plexus) run within the spinal canal, primarily anteriorly and laterally. These normal structures can sometimes be mistaken for disc herniations if not carefully evaluated, especially if engorged. Phleboliths (calcifications within veins) can occasionally be seen.

Disc herniations most commonly occur at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels in the lumbar spine. Herniations can be central, paracentral (most common), foraminal, or far-lateral, affecting different neural structures.

Preparation for Spine CT

Preparation for a spine CT scan is usually straightforward:

- Clothing: Wear comfortable clothing without metal snaps, zippers, or buttons in the area being scanned (neck or back). You may be asked to change into a hospital gown.

- Metal Objects: Remove jewelry (necklaces, some earrings), hairpins, and any removable dental appliances if scanning the cervical spine.

- Contrast Media: Most routine spine CT scans for evaluating bone or degenerative changes are done *without* intravenous (IV) contrast. If IV contrast is planned (e.g., to evaluate infection, tumor, or post-operative complications), you may be asked to fast for a few hours beforehand. Inform the staff about any allergies (especially to iodine/contrast) or kidney problems.

- CT Myelogram: If a CT Myelogram is scheduled (where contrast is injected into the spinal fluid before the CT), specific preparation instructions will be given, which may involve fasting and adjusting certain medications.

- Pregnancy: Inform your doctor and the technologist if there is any chance you might be pregnant.

The Spine CT Procedure

The procedure is similar to other CT scans:

- You will lie on the CT table, usually flat on your back. Pillows or supports may be used for comfort and positioning.

- The table moves into the scanner's gantry. The technologist will provide instructions via intercom.

- You need to remain very still during the scan. Breathing instructions are usually not required for spine CT unless the very upper or lower parts overlapping the chest/abdomen are included.

- If IV contrast is used, it will be injected through a line in your arm during the scan; you may feel a temporary warm sensation.

- The scan itself is quick, typically taking only a few minutes for the image acquisition.

Risks and Benefits

Benefits:

- Provides excellent detail of bone structures, making it superior for diagnosing fractures, evaluating bone healing/fusion, and assessing bony stenosis.

- Fast and widely available, crucial in trauma settings.

- Can clearly identify calcified disc herniations or ligament calcification (e.g., OPLL).

- Useful for patients who cannot undergo MRI (e.g., due to incompatible implants).

- Effective for guiding spinal interventions like biopsies and injections.

- Allows for multiplanar and 3D reconstructions for better anatomical understanding.

Risks:

- Ionizing Radiation: Involves radiation exposure, carrying a small cumulative lifetime risk. Doses are optimized, and the benefit typically outweighs the risk for indicated scans.

- Contrast Media Risks (if IV contrast used): Small risk of allergic-like reactions or potential impact on kidney function in susceptible individuals (see general CT risks).

- Limited Soft Tissue Detail: While CT shows soft tissues, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) generally provides superior detail of the spinal cord, nerve roots, non-calcified discs, ligaments, and bone marrow edema. MRI is often the preferred modality for evaluating disc herniations, spinal cord conditions, and soft tissue tumors/infections when available and not contraindicated.

- Pregnancy: Generally avoided unless medically necessary.

References

- Radiological Society of North America (RSNA) & American College of Radiology (ACR). (2022). Spine CT (Computed Tomography). RadiologyInfo.org. Retrieved from https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/ct-spine

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (2022). CT scan. Mayo Clinic Patient Care & Health Information. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/ct-scan/about/pac-20393675

- Hunter, T. B., & Taljanovic, M. S. (2003). Medical Devices of the Head, Neck, and Spine. *Radiographics*, 23(3), 731–748. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.233025117 [Note: Example of imaging considerations with hardware]

- Learch, T. J. (2007). Imaging of the Lumbar Spine. *Radiologic Clinics of North America*, 45(4), 607–624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcl.2007.05.003

- American College of Radiology. (2023). ACR Manual on Contrast Media. Retrieved from https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/Contrast-Manual