Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Understanding Spondyloarthrosis (Facet Joint Osteoarthritis)

- Diagnosis of Spondyloarthrosis of the Intervertebral Joints

- Treatment of Spondyloarthrosis of the Intervertebral Joints

- Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Spinal Pain

- Potential Complications of Spondyloarthrosis

- Prevention and Lifestyle Management

- When to Consult a Spine Specialist

- References

Understanding Spondyloarthrosis (Facet Joint Osteoarthritis)

Definition and Pathophysiology

Spondyloarthrosis, also commonly known as facet joint osteoarthritis or simply facet arthropathy, is a degenerative condition affecting the zygapophyseal joints (facet joints) of the human spinal column. These are true synovial joints located at the back of the spine, connecting adjacent vertebrae and contributing to spinal stability and guiding movement. Spondyloarthrosis is a dystrophic process that primarily involves damage to the articular cartilage covering the surfaces of these joints and the joint capsule. In its initial stages, inflammation (arthritis) of these joints often precedes the degenerative changes characteristic of spondyloarthrosis.

The development of spondyloarthrosis of the intervertebral joints is typically a gradual process. While some degree of facet joint degeneration can be considered a physiological part of aging, particularly in adulthood, various factors can accelerate or exacerbate this process.

Common Locations and Predisposing Factors

The segments of the spine that experience the maximum range of motion are most susceptible to developing spondyloarthrosis. Consequently, it most frequently affects:

- Cervical Spine (Neck): Due to its high mobility involving flexion, extension, lateral bending, and rotation.

- Lumbar Spine (Lower Back): Also highly mobile and subject to significant weight-bearing stresses.

The thoracic spine is less commonly affected by symptomatic spondyloarthrosis due to its inherent stability provided by the rib cage.

Factors that can promote or predispose to the occurrence of spondyloarthrosis include:

- Age: It is the most common type of intervertebral joint damage, typically occurring in middle-aged and elderly patients.

- Trauma: Acute injuries to the spine (e.g., whiplash, fractures) can damage facet joints.

- Chronic Overload: Repetitive microtrauma or sustained mechanical stress on specific spinal motion segments due to occupational activities, poor posture, or certain sports.

- Degenerative Disc Disease: As intervertebral discs lose height and hydration, abnormal loads are transferred to the facet joints, accelerating their degeneration.

- Spinal Instability: Conditions like spondylolisthesis can lead to abnormal facet joint mechanics.

- Obesity: Increases mechanical stress on the spine.

- Genetic Predisposition: Some individuals may be genetically more susceptible to osteoarthritis.

Clinical Symptoms and Impact on Neural Structures

Patients with osteoarthritis of the intervertebral joints (spondyloarthrosis) primarily complain of pain localized to the affected region of the spine (neck, mid-back, or lower back). Key characteristics of facet joint pain include:

- Pain that typically worsens with movement, especially extension (bending backward), twisting, or prolonged standing/sitting.

- Stiffness and limited range of motion in the affected spinal segment.

- Pain that often improves with rest.

- Localized tenderness over the affected facet joints.

- Pain may radiate in a non-dermatomal pattern (e.g., into the buttocks, thighs, shoulders, or occiput), sometimes referred to as "facet syndrome."

Nonspecific systemic symptoms like fatigue, malaise, or fever are generally absent in uncomplicated spondyloarthrosis, distinguishing it from inflammatory arthritides. The severity of symptoms does not always correlate with radiographic findings; some patients experience significant pain with minimal X-ray changes, while others with advanced osteophyte formation (spurs, ridges, or even bony bridges between vertebrae) may have few complaints, especially in middle-aged or elderly individuals.

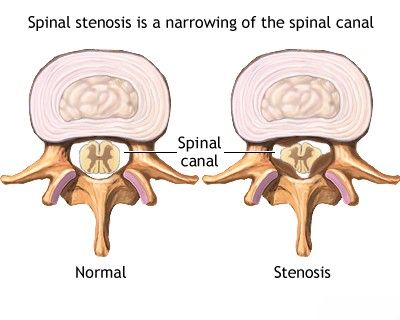

Degenerative changes associated with spondyloarthrosis, such as hypertrophy (enlargement) of the facet joints and osteophyte formation, can lead to narrowing (stenosis) of the spinal canal or neural foramina (the openings where nerve roots exit the spine). This can result in:

- Radiculopathy: Compression or irritation of spinal nerve roots, causing pain, numbness, tingling, or weakness in the distribution of the affected nerve (e.g., sciatica if lumbar roots are involved, arm pain if cervical roots are involved).

- Myelopathy: Compression of the spinal cord (more common in cervical or thoracic spondyloarthrosis with significant spinal canal stenosis), leading to symptoms like gait disturbance, weakness, spasticity, and bowel/bladder dysfunction.

- Neurogenic Claudication: Multiple radiculopathies at the lumbar level due to lumbar spinal stenosis (often contributed to by facet hypertrophy) can cause pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs that is typically provoked by walking or standing and relieved by sitting or leaning forward (flexion). This "intermittent claudication" of spinal origin occurs because nerve roots become trapped between the posterior surface of the vertebral body and hypertrophied ligaments (e.g., ligamentum flavum) or facet joints. Congenital narrowness of the lumbar spinal canal, particularly at the L4-L5 and L5-S1 levels, can predispose individuals to symptomatic stenosis with even moderate degenerative changes from intervertebral disc damage or spondyloarthrosis.

Patients with spondyloarthrosis often complain of pain, heaviness, and stiffness in the neck or lower back, particularly in the morning, which tends to improve within several tens of minutes to an hour after the patient "warms up" or stretches. In the acute stage of the disease, sharp pains with associated muscle stiffness (protective muscle spasm) can occur. This protective muscular reaction, if prolonged and leading to an antalgic posture (e.g., antalgic scoliosis), can itself become a source of chronic pain and problems if treatment is not appropriate, potentially leading to a secondary myofascial pain syndrome with fibromyalgia-like symptoms and typical trigger points in muscle bundles.

Advanced spondyloarthrosis can contribute to stenosis (narrowing) of the spinal canal, potentially leading to compression of the spinal cord. This MRI illustrates such compression, often exacerbated by hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum.

Diagnosis of Spondyloarthrosis of the Intervertebral Joints

The diagnosis of spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis) is generally not difficult for experienced clinicians and is based on a combination of clinical findings and imaging results.

- Clinical History and Physical Examination:

- During a consultation, if a patient presents with typical complaints (e.g., localized spinal pain worse with extension/twisting, morning stiffness improving with movement) and the results of an external examination of spinal biomechanics (range of motion, tenderness over facet joints, neurological assessment) are consistent, spondyloarthrosis can be suspected.

- Imaging Studies:

- Plain X-rays: An overview X-ray of the spine (AP and lateral views, sometimes oblique views for facet joints) is often the initial imaging modality. It can show characteristic signs of facet joint osteoarthritis, such as joint space narrowing, osteophyte formation (bone spurs), and sclerosis (increased bone density) of the articular processes.

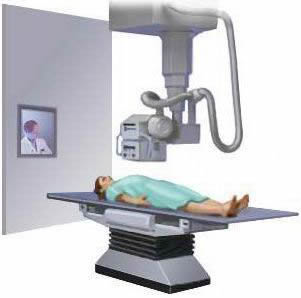

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: CT provides more detailed visualization of the bony anatomy of the facet joints, osteophytes, and any associated spinal canal or foraminal stenosis. It is particularly useful for assessing bony details when planning interventions.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): While less sensitive for direct visualization of facet cartilage, MRI is excellent for evaluating associated soft tissue structures, intervertebral discs, ligaments, nerve roots, and the spinal cord. It can show facet joint effusions (fluid), synovitis (inflammation of the joint lining), and consequences of facet hypertrophy like foraminal stenosis or spinal cord compression. Myelography (historically used with X-rays, now sometimes with CT or MRI) after injecting contrast into the spinal canal can help visualize narrowing (stenosis).

- Diagnostic Facet Joint Injections (Blocks): If facet joint pain is suspected, an injection of local anesthetic (with or without corticosteroid) directly into the facet joint or around the medial branches of the dorsal rami (nerves that supply the facet joints) can be performed under imaging guidance (fluoroscopy or CT). Significant pain relief after the block supports the facet joint as the source of pain.

Educational video: A CT scan of the spine may be used to evaluate various spinal conditions, including spondyloarthrosis, herniated discs, stenosis, scoliosis, traumatic injuries, tumors, congenital issues like spina bifida, vascular problems, or infections.

These hardware-assisted diagnostic procedures can reveal narrowing of the lumbar spinal canal (stenosis) in patients if present.

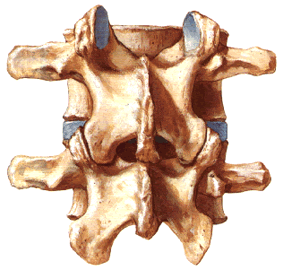

Radiography of the spine in a direct (anteroposterior) projection can reveal signs of spondyloarthrosis affecting the intervertebral (facet) joints, such as osteophytes and joint space narrowing.

Treatment of Spondyloarthrosis of the Intervertebral Joints

The treatment of spondyloarthrosis of the intervertebral joints involves a multimodal approach targeting the damaged articular surfaces and associated symptoms. The standard course of treatment typically lasts from 1 to 3 weeks for acute exacerbations but often requires long-term management strategies.

Conservative Management Strategies

- Drug Therapy (Pharmacotherapy):

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Such as ibuprofen, naproxen, diclofenac, or COX-2 inhibitors, to reduce pain and inflammation.

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen (paracetamol) for pain relief. In cases of severe pain, stronger analgesics like tramadol or, rarely and for short periods, opioids may be considered.

- Muscle Relaxants: To alleviate associated muscle spasms.

- Topical Analgesics: Creams or patches containing NSAIDs, capsaicin, or lidocaine.

- Hormones (Corticosteroids): Oral corticosteroids are generally not used for uncomplicated spondyloarthrosis but may be considered for severe acute flare-ups or if there is significant nerve root inflammation (radiculitis). See therapeutic injections below.

- Physiotherapy: A cornerstone of treatment, aiming to:

- Reduce pain and inflammation (e.g., using heat/cold therapy, Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation - TENS, ultrasound - historically UHF).

- Improve range of motion and flexibility through specific exercises.

- Strengthen core and paraspinal muscles to support the spine.

- Improve posture and body mechanics.

- Manual Therapy: Techniques such as spinal mobilization or gentle manipulation performed by qualified therapists (physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths) can help improve joint mobility and reduce pain.

- Massage Therapy: Can help relieve muscle tension and pain.

- Therapeutic Exercise and Swimming: A tailored exercise program, including general fitness and specific spinal exercises, is crucial. Swimming or water-based exercises are often well-tolerated as they reduce load on the joints. This is usually recommended after the acute pain from the main course of treatment subsides.

- Spinal Traction: May be used in some cases, particularly for cervical spondyloarthrosis with radicular symptoms, but is generally not performed during the acute, painful stage.

It is advisable to undergo several courses of conservative treatment, even if the patient with spondyloarthrosis is not experiencing an acute exacerbation. This proactive approach can significantly reduce the risk of recurrent painful episodes and prevent the progression of spondyloarthrosis over many years.

Restoration of the range of lost movements in the intervertebral joints affected by spondyloarthrosis during the course of treatment is key to preventing premature destruction of intervertebral discs, which could otherwise lead to the formation of disc protrusions and herniated discs in the cervical and lumbar spine.

In the treatment of spondyloarthrosis, physiotherapy plays a crucial role in accelerating the reduction of swelling (puffiness), inflammation, and soreness, as well as restoring the range of motion in the affected intervertebral joints, for instance, of the lumbar spine.

Interventional Pain Management (Injections/Blockades)

Facet joints can be treated with therapeutic injections (blockades) when conventional conservative treatment for spondyloarthrosis (referred to as spondyloarthritis in some contexts here, though spondyloarthrosis is more specific for osteoarthritis) is not beneficial. These injections typically involve instilling low doses of a local anesthetic (e.g., lidocaine, bupivacaine) and a corticosteroid (e.g., triamcinolone, methylprednisolone) directly into the lumen (cavity) of the affected facet joint or around the medial branch nerves that supply the joint. This procedure is performed under imaging guidance (fluoroscopy or CT). When combined with a properly selected physiotherapy regimen, these injections can provide significant and often long-term relief from lumbar and sacral pain originating from facet joints.

Radiofrequency Neurotomy (Ablation)

If diagnostic facet joint or medial branch blocks provide significant but temporary pain relief, radiofrequency neurotomy (RFN) or ablation of the medial branch nerves may be considered. This minimally invasive procedure uses heat generated by radiofrequency waves to create a lesion on the targeted pain-transmitting nerves, thereby interrupting pain signals from the arthritic facet joint. The procedure for radiofrequency destruction of painful nerve endings is generally well-tolerated by patients and is often performed on an outpatient basis, without requiring hospitalization. Pain relief can last for several months to over a year.

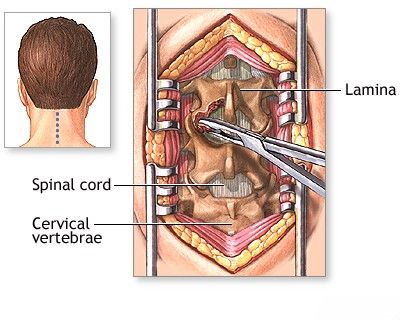

In cases where spondyloarthrosis contributes to severe spinal stenosis with compression of the spinal cord or nerve roots (often due to associated hypertrophy of the posterior longitudinal ligament and ligamentum flavum), surgical decompression procedures such as hemilaminectomy or laminectomy may be performed.

Surgical Intervention

Surgery is generally reserved for cases of spondyloarthrosis with severe, intractable pain unresponsive to comprehensive conservative and interventional pain management, or when there is significant neurological compromise due to associated conditions like severe spinal stenosis or spondylolisthesis with instability.

Surgical options may include:

- Decompressive Surgery: Procedures like laminectomy, laminotomy, or foraminotomy to relieve pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots caused by hypertrophied facet joints, osteophytes, or thickened ligaments. An operation to decompress the contents of the spinal canal aims to eliminate symptoms of nerve and spinal cord compression.

- Spinal Fusion: If there is associated spinal instability, or if extensive decompression might create instability, spinal fusion may be performed to stabilize the affected segments. To prevent possible postoperative spinal instability after decompression, stabilizing systems (e.g., pedicle screws, rods, interbody cages) are often installed.

Radiculopathy of the lumbar spinal nerves resulting from spondylarthritic changes (lumbar spondylitis is a less precise term here) can present with neurological manifestations similar to myelopathy of the cervical spinal cord in terms of impact on function, though the specific symptoms differ (e.g., cauda equina syndrome if multiple lumbosacral roots are compressed).

Differential Diagnosis of Chronic Spinal Pain

Chronic spinal pain attributed to spondyloarthrosis must be differentiated from other potential causes:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Spondyloarthrosis (Facet Joint Osteoarthritis) | Localized axial pain, worse with extension/twisting, morning stiffness <30 min. Imaging shows facet joint degeneration. Pain relief with diagnostic facet blocks. |

| Degenerative Disc Disease (Osteochondrosis) | Axial pain, often worse with flexion or prolonged sitting. Imaging shows disc space narrowing, desiccation, endplate changes. Often coexists with spondyloarthrosis. |

| Intervertebral Disc Herniation | Predominantly radicular pain, numbness, weakness in a dermatomal pattern. Positive nerve tension signs (e.g., straight leg raise). MRI confirms disc herniation. |

| Spinal Stenosis | Neurogenic claudication (leg pain/numbness/weakness with walking/standing, relieved by flexion/sitting). Spondyloarthrosis is a major cause of stenosis. |

| Inflammatory Spondyloarthropathies (e.g., Ankylosing Spondylitis) | Inflammatory back pain (morning stiffness >30 min, improves with exercise, night pain), sacroiliitis. Elevated inflammatory markers, HLA-B27. |

| Myofascial Pain Syndrome | Localized or regional muscle pain with tender trigger points, referred pain patterns. Often secondary to underlying spinal pathology or postural strain. |

| Spondylitis (Infectious) | Severe localized pain, often constitutional symptoms (fever, malaise). Elevated inflammatory markers. MRI shows vertebral/disc infection. |

| Spinal Tumors (Primary or Metastatic) | Persistent pain, often worse at night, not relieved by rest. May have neurological deficits, weight loss. Imaging is key. |

Potential Complications of Spondyloarthrosis

While often a source of chronic pain and stiffness, advanced spondyloarthrosis can lead to more significant complications:

- Chronic Pain and Disability: Impairing daily activities and quality of life.

- Nerve Root Compression (Radiculopathy): Due to foraminal stenosis caused by facet hypertrophy and osteophytes.

- Spinal Cord Compression (Myelopathy): In the cervical or thoracic spine if central spinal stenosis develops.

- Lumbar Spinal Stenosis with Neurogenic Claudication.

- Formation of Synovial Cysts: Degenerative facet joints can develop cysts that may compress neural structures.

- Segmental Instability: In some cases, severe facet degeneration can contribute to spinal instability.

- Secondary Myofascial Pain Syndromes.

Prevention and Lifestyle Management

While age-related degeneration is inevitable to some extent, certain measures may help manage symptoms or slow progression:

- Regular Exercise: Maintaining core strength, flexibility, and overall fitness. Low-impact exercises like swimming, walking, or cycling are often recommended.

- Weight Management: Reducing excess body weight decreases stress on spinal joints.

- Good Posture: Maintaining proper posture during daily activities.

- Ergonomics: Using ergonomic furniture and techniques at work and home.

- Avoiding Overuse/Strain: Modifying activities that exacerbate pain.

When to Consult a Spine Specialist

Individuals experiencing persistent or worsening back or neck pain, especially if associated with stiffness, radiating symptoms, weakness, numbness, or gait disturbance, should consult a spine specialist (e.g., orthopedic spine surgeon, neurosurgeon, physiatrist, or rheumatologist with expertise in spinal disorders). Early diagnosis and a comprehensive management plan can help alleviate symptoms, improve function, and enhance quality of life.

References

- Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Falco FJ, Boswell MV. Management of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. World J Orthop. 2016 Jan 18;7(1):38-50.

- Cohen SP, Raja SN. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of lumbar zygapophysial (facet) joint pain. Anesthesiology. 2007 Mar;106(3):591-614.

- Kuslich SD, Ulstrom CL, Michael CJ. The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: a report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991 Apr;22(2):181-7.

- Kalichman L, Hunter DJ. Lumbar facet joint osteoarthritis: a review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Oct;37(2):69-80.

- Perolat R, Kastler A, Nicot B, et al. Facet joint syndrome: from diagnosis to interventional management. Insights Imaging. 2018 Oct;9(5):773-789.

- Gellhorn AC, Katz JN, Suri P. Osteoarthritis of the spine: the facet joints. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013 Apr;9(4):216-24.

- Vanelderen P, Rouwette T, De Vooght P, et al. Radiofrequency treatment for facet joint pain. World J Anesthesiol. 2012 May 27;1(2):38-43.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome