Spine abnormalities

- Understanding Spine Abnormalities

- Specific Congenital Spinal Abnormalities

- Acquired Spinal Changes Contributing to Symptoms

- Diagnosis of Spinal Abnormalities

- Treatment of Spinal Malformations and Associated Symptoms

- Differentiating Causes of Back Pain with Underlying Spinal Abnormalities

- Complications and Long-Term Considerations

- When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Spine Abnormalities

Spinal abnormalities encompass a wide range of congenital (present at birth) developmental anomalies and acquired structural changes affecting the vertebral column. These abnormalities can significantly influence the biomechanics of the spine, predisposing individuals to various spinal disorders, pain syndromes, and neurological complications.

Significance and Impact

While some spinal anomalies may remain asymptomatic throughout life and are discovered incidentally, others can compromise spinal stability, lead to premature degenerative changes, or directly impinge on neural structures (spinal cord and nerve roots). Congenital anomalies of the spine, such as non-closure of the vertebral arch (spina bifida), transitional vertebrae like sacralization or lumbarization, and spondylolisthesis (slipping of one vertebra relative to another), are of particular importance.

These developmental variations, while not always directly injurious to nerve roots themselves, can indicate an underlying predisposition or a general "dysraphic status" (defective neural tube closure or development) in the patient. Furthermore, such anomalies can reduce the static stability and load-bearing capacity of the spine. The lumbar spine, in particular, bears the substantial weight of the erect torso and is the most mobile segment of the spine, making it highly susceptible to traumatic factors and degenerative processes, especially when underlying abnormalities are present.

Specific Congenital Spinal Abnormalities

Developmental defects of the spine are frequently identified in the cervical and lumbosacral regions due to their complex embryological development and biomechanical stresses.

Klippel-Feil Syndrome (Short Neck Syndrome)

Klippel-Feil syndrome is a congenital condition characterized by the fusion of two or more cervical vertebrae. This results in a visibly short neck, limited head and neck mobility, and often a low posterior hairline. The fused cervical vertebrae can appear as a shapeless bone mass on imaging. Scoliosis or kyphoscoliosis of the thoracic or lumbar spine often coexists.

Neurologically, Klippel-Feil syndrome may be asymptomatic, or it can be accompanied by cervical radicular syndrome (pain, numbness, or weakness in the arms due to nerve root compression) and signs of upper motor neuron involvement (pyramidal signs) if the spinal cord is affected. This syndrome is frequently associated with other spinal anomalies, such as spina bifida in the lumbar region and the presence of cervical ribs. Anomalies in the development of the odontoid process (dens) of the C2 vertebra, such as aplasia (absence) or hypoplasia (underdevelopment), are often found in individuals with Klippel-Feil syndrome, as well as in Down syndrome or Morquio syndrome (a type of mucopolysaccharidosis, historically sometimes referred to as Mark syndrome in some regional literature).

Accessory Cervical Rib Syndrome

An accessory cervical rib is an extra rib arising from the seventh cervical vertebra (C7). While often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on X-rays, an accessory cervical rib can cause symptoms (thoracic outlet syndrome) if it compresses the brachial plexus (nerves supplying the arm) or the subclavian artery or vein. Symptoms typically manifest under the influence of adverse factors such as cold exposure, trauma, or infection. Clinical manifestations include neuralgic pain in the shoulder, which can radiate down the arm, often accompanied by paresthesias (tingling, numbness). Vasomotor and trophic disturbances (e.g., pale, cyanotic, cold skin; excessive sweating; increased pilomotor reflex) may also occur. In some cases, muscle weakness and atrophy in the arm and hand can develop. The presence of autonomic disturbances and the sympathetic nature of some pain patterns suggest involvement or irritation of cervical sympathetic nerve fibers by the accessory rib.

Spina Bifida (Split Vertebra)

Spina bifida is one of the most common neural tube defects and represents a significant developmental anomaly of the spine. It consists of incomplete closure (non-overgrowth or cleavage) of the vertebral arches, most commonly in the lumbosacral region (LV lumbar or SI sacral vertebra), though it can occur in other spinal segments less frequently. Rarely, the splitting can involve the vertebral body itself.

Spina bifida is broadly classified into two main types:

Spina Bifida Occulta (Closed)

This is the more common and milder form. The vertebral defect is covered by skin, and the spinal cord and meninges are usually not herniated. In many cases, spina bifida occulta is asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on X-rays. However, it can sometimes be associated with subtle neurological signs or predispose to certain problems:

- Cutaneous Markers: A patch of hair, a dimple, a birthmark (nevus), or a lipoma over the affected spinal area may be present.

- Neurological Symptoms (less common): Mild pain in the lumbosacral region, enuresis (bed-wetting), foot deformities, or subtle leg weakness. Cicatricial (scar-like) changes in the area of the defect can tether or irritate nerve roots, causing neurogenic disorders such as leg paresis with loss of tendon reflexes, radicular sensory disturbances, and trophic or vasomotor symptoms (e.g., ulcers, edema, local hypertrichosis, skin changes).

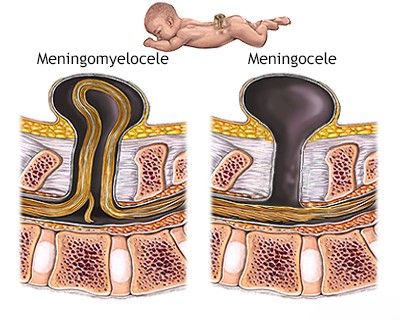

Spina Bifida Aperta (Open) - Meningocele and Meningomyelocele

This is a much less common but more severe form, occurring in approximately one per 1000–1500 newborns. In spina bifida aperta, there is an open vertebral defect through which the spinal cord elements can protrude, forming a visible sac-like lesion on the back. It is usually associated with dysplasia (abnormal development) of the spinal cord, meninges, and nerve roots.

- Meningocele: The hernial sac contains only meninges (membranes covering the spinal cord) and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The spinal cord itself is usually in its normal position and may be functionally intact or only mildly affected. Neurological deficits are less common or milder.

- Meningomyelocele (Myelomeningocele): This is the most common and severe form of spina bifida aperta. The hernial sac contains meninges, CSF, and a portion of the abnormally developed spinal cord and/or nerve roots. This invariably leads to significant neurological deficits below the level of the lesion, including:

- Severe motor impairment (paralysis or paresis of the legs).

- Sensory loss.

- Bowel and bladder dysfunction (incontinence).

- Trophic disorders (e.g., pressure sores).

- Skeletal deformities (e.g., clubfoot, hip dislocation, scoliosis).

- Myeloschisis (Rachischisis): The most severe form, where the neural tube fails to close entirely, and the spinal cord is exposed on the surface. This is often incompatible with long-term survival.

In some severe cases of open spina bifida, the protruding hernial sac is not covered by muscles or normal skin; its wall may consist of the exposed posterior surface of the dysplastic spinal cord itself (as in myeloschisis or some forms of meningomyelocele).

Diastematomyelia

Diastematomyelia is a rare congenital malformation characterized by a sagittal (longitudinal) splitting or division of the spinal cord into two hemicords, usually in the lower thoracic or lumbar region. This division is often caused by a bony, cartilaginous, or fibrous septum or spur that traverses the spinal canal, tethering the spinal cord. This tethering can restrict the normal upward migration (ascent) of the spinal cord during growth, leading to progressive neurological deficits. Diastematomyelia is frequently associated with other spinal anomalies, including spina bifida, vertebral segmentation defects, and scoliosis. Its clinical picture can be similar to that of other tethered cord syndromes or spina bifida occulta with neurological manifestations, including leg weakness, sensory changes, bowel/bladder dysfunction, and foot deformities.

In cases of diastematomyelia, computed tomography (CT) or MRI of the spine often reveals an enlarged spinal canal with a characteristic bony, cartilaginous, or fibrous bridge dividing the spinal cord, frequently associated with divergence of the edges of a vertebral arch bone defect (spina bifida).

Fixation of the spinal cord and its membranes, as seen in diastematomyelia or other forms of tethered cord syndrome, can lead to a low-lying conus medullaris (the terminal end of the spinal cord). This can also contribute to the development of Arnold-Chiari malformation (a congenital defect involving the cerebellum and brainstem), which can also be caused by spina bifida, a congenitally low spinal cord position, or short spinal nerve roots.

Transitional Vertebrae: Sacralization and Lumbarization

Transitional vertebrae are anomalies at the lumbosacral junction where a vertebra has characteristics of both spinal regions. These include:

- Sacralization of L5: The fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) becomes partially or completely fused with the first sacral vertebra (S1). This can involve one or both transverse processes of L5 articulating or fusing with the sacrum or ilium.

- Lumbarization of S1: The first sacral vertebra (S1) fails to fuse with the rest of the sacrum and essentially functions as a sixth lumbar vertebra (L6).

Clinically, sacralization and lumbarization are often asymptomatic. However, they can sometimes alter spinal biomechanics and predispose to low back pain or radicular symptoms (sciatica) affecting the L5 or S1 nerve roots due to altered stress distribution or narrowing of intervertebral foramina. The causes of these developmental defects, like other spinal anomalies, are complex and involve disruptions during embryological development of the spine and spinal cord, similar to factors influencing brain and skull anomalies.

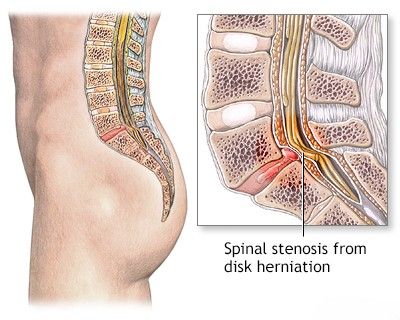

Congenital Spondylolisthesis

Congenital spondylolisthesis is a type of congenital spinal instability resulting from developmental defects in the supporting and fixing bone structures (e.g., pars interarticularis, facets) or ligamentous apparatus of the spine. This is most common at the L5-S1 level. The underdevelopment of these structures leads to excessive mobility and allows one vertebra to slip forward (anterolisthesis) or backward (retrolisthesis) relative to the vertebra below it. This slippage can lead to narrowing of the spinal canal or intervertebral foramina, potentially causing compression of the spinal cord, cauda equina, or nerve roots, resulting in back pain, radicular pain, or neurological deficits.

Displacement of vertebrae, or spondylolisthesis, is a manifestation of spinal instability that can lead to compression of nerve roots or the spinal cord.

Acquired Spinal Changes Contributing to Symptoms

While the focus is on congenital abnormalities, it's important to note that acquired changes can also lead to spinal diseases and symptoms. These include, but are not limited to:

- Degenerative Conditions: Osteochondrosis (disc degeneration), spondylosis (osteophytes), spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis), and spinal stenosis.

- Trauma: Compression fractures, dislocations and subluxations, and whiplash injuries.

- Inflammatory Conditions: Ankylosing spondylitis, sacroiliitis, spondylitis (infectious or inflammatory).

- Metabolic Bone Diseases: Osteoporosis.

- Neoplasms: Vertebral hemangiomas, primary or metastatic spinal tumors causing spinal cord compression or non-compressive myelopathies.

These acquired conditions can interact with or be exacerbated by underlying congenital abnormalities.

Diagnosis of Spinal Abnormalities

Diagnosing spinal abnormalities involves a comprehensive approach:

- Clinical History: Detailed history of symptoms (pain, weakness, numbness, bowel/bladder dysfunction), developmental milestones, family history of spinal problems.

- Physical Examination: Neurological assessment (motor, sensory, reflexes), musculoskeletal examination (range of motion, palpation for tenderness, observation for deformities like scoliosis or abnormal posture). Inspection for cutaneous markers of spina bifida occulta.

- Imaging Studies:

- X-rays: Standard anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views of the spine can reveal many bony abnormalities (e.g., spina bifida occulta, transitional vertebrae, spondylolisthesis, fractures, degenerative changes). Flexion-extension views can assess for instability.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Provides excellent detail of bony structures, useful for complex fractures, assessing fusion, or delineating bony spurs in diastematomyelia.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): The modality of choice for evaluating soft tissues, including the spinal cord, nerve roots, intervertebral discs (for herniations), ligaments, and detecting inflammation or tumors. Essential for diagnosing meningocele, meningomyelocele, diastematomyelia, and spinal cord compression.

- Myelography (less common now): CT myelography may be used if MRI is contraindicated or inconclusive.

- Ultrasound: Can be used for prenatal diagnosis of spina bifida and in infants for evaluating the spinal cord before ossification of vertebral arches is complete.

- Electrophysiological Studies (EMG/NCS): May be used to assess nerve root or peripheral nerve function if radiculopathy or neuropathy is suspected.

- Genetic Testing: In some cases, if a specific genetic syndrome associated with spinal abnormalities is suspected.

Treatment of Spinal Malformations and Associated Symptoms

The treatment approach depends on the specific type of spinal abnormality, the severity of symptoms, the presence of neurological deficits, and the patient's age and overall health. Many asymptomatic congenital anomalies require no treatment, only observation.

Conservative Management

For radicular symptoms (nerve root pain) or back pain associated with spinal anomalies but without severe neurological compromise or instability, conservative treatment is often the first line:

- Drug Therapy:

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesics for pain relief.

- Muscle relaxants for muscle spasm.

- Neuropathic pain medications (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin) for radicular pain.

- Hormones (corticosteroids) may be used systemically for severe inflammation or as epidural injections.

- Therapeutic Injections: Epidural steroid injections, facet joint injections, or nerve root blocks can provide diagnostic information and therapeutic relief for pain originating from specific spinal structures. These involve injecting anesthetic and/or cortisone into the intervertebral joint cavity, spinal canal, or trigger points in muscles.

- Manual Therapy: Techniques such as muscle energy techniques, joint mobilization, and specific radicular techniques may be employed by trained therapists.

- Physiotherapy: A crucial component, including exercises to strengthen core muscles, improve posture and flexibility, and reduce pain. Modalities like heat, cold, ultrasound, or TENS may be used.

- Acupuncture: May provide pain relief for some individuals.

- Bracing: Wearing a semi-rigid lumbosacral corset or other spinal orthosis can help limit painful motion in the lumbar spine, reduce inflammation in intervertebral joints, and relieve protective muscle tension and spasm. Corsets are selected by size and can be used repeatedly for recurrences of back pain. The need for a corset typically diminishes as back pain resolves.

When combined with a properly selected physiotherapy regimen, therapeutic injections can have a good and long-term effect on lumbar and sacral pain (sacrodynia) or pain in the neck, head, and arm, or pain in the thoracic spine and intercostal neuralgia.

In the management of back pain stemming from spinal abnormalities, physiotherapy focused on the lumbar region can accelerate the reduction of swelling (puffiness) and inflammation, alleviate soreness, and restore range of motion in the joints and muscles of the lower back.

For leg pain associated with sciatic neuritis due to compression from a disc hernia or protrusion (often linked to underlying spinal abnormalities), physiotherapy can accelerate pain and tingling relief and help restore normal sensation.

A variant of a semi-rigid lumbosacral corset, which can provide support and help in the treatment of back pain at the level of the lumbar spine.

An alternative design of a semi-rigid lumbosacral corset, also aimed at assisting in the treatment of back pain originating from the lumbar spine.

Surgical Management

Surgical treatment is reserved for specific situations:

- Spina Bifida Aperta (Meningocele/Meningomyelocele): Surgical closure of the back defect is typically performed within the first few days of life to prevent infection and protect neural tissue. Good results (in terms of survival and sac closure) are often observed with meningocele repair, where only meninges are involved. The prognosis for neurological function in meningomyelocele depends on the level and severity of spinal cord involvement. Spinal cord dysplasia often accompanies these conditions, impacting long-term outcomes.

- Symptomatic Tethered Cord Syndrome (e.g., with Diastematomyelia): Surgical untethering of the spinal cord may be necessary to prevent progressive neurological deterioration.

- Persistent Radicular Syndrome or Neurological Deficits: If conservative measures fail for symptoms caused by nerve root compression (e.g., from spondylolisthesis, severe foraminal stenosis due to transitional vertebrae, or accessory cervical ribs), surgical decompression and/or stabilization may be indicated. This can involve removal of cicatricial changes, adhesions, or the accessory cervical rib itself.

- Progressive Deformity or Instability: Surgical fusion and instrumentation may be needed for significant or progressive spondylolisthesis or other unstable spinal conditions.

- Arnold-Chiari Malformation: If symptomatic, posterior fossa decompression may be required.

The overall approach aims to relieve pain, decompress neural structures, stabilize the spine if necessary, and correct deformities where possible, while minimizing risks.

Supportive Measures

For individuals with significant neurological impairments, particularly from severe forms of spina bifida, comprehensive multidisciplinary care is essential, including:

- Orthopedic management for skeletal deformities.

- Urological management for bladder dysfunction.

- Gastrointestinal management for bowel dysfunction.

- Rehabilitation therapies (physical, occupational, speech).

- Psychosocial support for the patient and family.

- Specialized care for individuals with paralysis.

Differentiating Causes of Back Pain with Underlying Spinal Abnormalities

Many spinal abnormalities are asymptomatic. When pain occurs, it's important to determine if the abnormality is the direct cause or an incidental finding, with pain arising from other sources (e.g., muscle strain, disc degeneration).

| Spinal Abnormality | Potential Pain Mechanism / Symptoms | Common Coexisting/Alternative Pain Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Spina Bifida Occulta | Often asymptomatic. If symptomatic: low back pain, radicular pain due to associated nerve root tethering or irritation by fibrous bands. | Muscular strain, facet joint arthropathy, discogenic pain. |

| Sacralization / Lumbarization | Can alter biomechanics leading to premature disc degeneration at adjacent levels, facet joint arthropathy, or nerve root impingement (L5/S1). Sacroiliac pain. | Primary disc herniation, sacroiliitis from other causes. |

| Congenital Spondylolisthesis | Low back pain, radicular pain (sciatica) due to nerve root compression from slippage, neurogenic claudication. Hamstring tightness. | Isthmic spondylolisthesis (acquired pars defect), degenerative spondylolisthesis. |

| Klippel-Feil Syndrome | Neck pain, limited neck motion, cervical radiculopathy, myelopathy if severe stenosis or instability. Headaches. | Cervical degenerative disc disease, muscle tension headaches. |

| Accessory Cervical Rib | Thoracic outlet syndrome: arm/shoulder pain, numbness, tingling, weakness due to brachial plexus or subclavian vessel compression. | Cervical radiculopathy from disc herniation/foraminal stenosis, peripheral neuropathy, shoulder pathology (e.g., rotator cuff tear). |

Complications and Long-Term Considerations

Depending on the specific abnormality, long-term complications can include:

- Progressive neurological deficits (motor weakness, sensory loss, bowel/bladder dysfunction).

- Chronic pain syndromes (coccygodynia, sacrodynia, lumbago).

- Spinal deformity (e.g., scoliosis, kyphosis).

- Premature degenerative changes in the spine (osteoarthritis of sacroiliac joint, spondylosis).

- Hydrocephalus (often associated with meningomyelocele).

- Urinary tract infections and kidney damage (with neurogenic bladder).

- Psychosocial challenges and impact on quality of life.

Lifelong monitoring and multidisciplinary care are often required for individuals with significant spinal abnormalities.

When to Consult a Specialist

Consultation with a specialist (e.g., neurosurgeon, orthopedic spine surgeon, neurologist, physiatrist, pediatrician specializing in developmental disorders) is indicated when:

- A congenital spinal abnormality is diagnosed or suspected at birth or in early childhood.

- There is persistent or progressive back pain, neck pain, or radicular pain.

- Neurological symptoms develop (weakness, numbness, tingling, bowel/bladder changes).

- Visible spinal deformity or cutaneous markers are present.

- Symptoms are not improving with conservative management.

Early diagnosis and appropriate management can help mitigate symptoms, prevent progression, and improve long-term outcomes for individuals with spinal abnormalities.

References

- McNeely ML, Torrance G, Magee DJ. A systematic review of physiotherapy for spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis. Man Ther. 2003 May;8(2):80-91.

- North American Spine Society (NASS). Clinical Guidelines for Multidisciplinary Spine Care: Diagnosis and Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spondylolisthesis. 2nd ed. NASS; 2014.

- Tracy MR, Dormans JP, Kusumi K. Klippel-Feil syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004 Jul;(424):183-90.

- Gûlman B, Tuncay IÇ, Elhan A, Isikan UE. Anatomic study of the accessory cervical rib and its clinical importance. Clin Anat. 1994;7(5):280-3.

- Adzick NS, Sutton LN, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW. Successful fetal surgery for spina bifida. Lancet. 1998 Nov 21;352(9141):1675-6. (Historical context for severe forms)

- O'Rahilly R, Müller F. Developmental stages in human embryos: revised and new measurements. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192(2):73-84. (Embryology context)

- Dias MS. Neurosurgical management of occult spinal dysraphism. Neurosurg Focus. 2004 Jan 15;16(1):E7.

- Castellvi AE, Goldstein LA, Chan DP. Lumbosacral transitional vertebrae and their relationship with disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1984 Oct;9(7):765-6.

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome