Syringomyelia

Understanding Syringomyelia

Definition and Pathophysiology

Syringomyelia is a chronic, often progressive neurological disorder characterized by the formation of a fluid-filled cavity or cyst, known as a syrinx, within the spinal cord. This condition is a type of myelopathy (disease affecting the spinal cord). The syrinx typically develops in the central part of the spinal cord, often in the region of the central canal, and can expand over time, compressing or destroying surrounding nerve tissue and disrupting the normal flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

The slow enlargement of the syringomyelic cavity can lead to a narrowing or complete blockage of the subarachnoid space around the spinal cord at the level of the syrinx. While syringomyelic cavities may sometimes be separated from the central canal, they are usually connected to it or arise from its dilation.

Etiology: Congenital and Acquired Forms

By its origin, syringomyelia is often considered an abnormality of spinal cord development (congenital or developmental syringomyelia). However, it can also form secondary to other conditions (acquired syringomyelia):

- Spinal cord injuries: Post-traumatic syringomyelia can develop months or years after a spinal cord injury.

- Primary intracerebral (intramedullary) spinal cord tumors: Tumors within the spinal cord can lead to syrinx formation.

- External spinal cord compression with necrosis: Prolonged compression causing damage to the central part of the spinal cord.

- Spinal arachnoiditis: Inflammation and scarring of the arachnoid membrane surrounding the spinal cord can obstruct CSF flow and lead to syrinx formation.

- Hematomyelia: Bleeding into the spinal cord.

- Necrotic myelitis: Inflammatory conditions causing death of spinal cord tissue.

In cases of congenital or developmental syringomyelia, the disease often begins with a lesion in the middle parts of the cervical spinal cord and can then spread upwards towards the medulla oblongata (brainstem) – a condition known as syringobulbia – and downwards to the lumbar level of the spinal cord. Syringomyelic cavities are frequently located eccentrically (off-center) within the spinal cord, which can cause neurological symptoms presenting with a unilateral conductive character (affecting one side of the body more) or an asymmetry of tendon and periosteal reflexes.

Associated Congenital Anomalies

In many instances, syringomyelia, particularly the congenital form, is associated with other congenital anomalies of the brain, skull base, and spine, especially those affecting the craniovertebral junction (the area where the skull meets the cervical spine). These include:

- Chiari Malformations (often Type I, formerly Arnold-Chiari anomaly): A condition where cerebellar tonsils herniate through the foramen magnum, obstructing CSF flow. This is one of the most common conditions associated with syringomyelia.

- Myelomeningocele: A severe form of spina bifida where the spinal cord and its coverings protrude through an opening in the vertebral column.

- Basilar Impression (Platybasia): An upward displacement of the base of the skull, potentially compressing the brainstem.

- Atresia of the Foramen of Magendie: Congenital blockage of one of the outlets for CSF from the fourth ventricle of the brain.

- Dandy-Walker Cyst/Malformation: A congenital brain malformation involving the cerebellum and the fluid-filled spaces around it.

- Other spinal dysraphisms or vertebral anomalies.

On this sagittal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan of the cervical spinal cord, two distinct syringomyelic cavities (syrinxes) filled with cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are clearly visible within the substance of the spinal cord (indicated by arrows).

Clinical Symptoms of Syringomyelia and Syringobulbia

The main clinical symptoms of syringomyelia often resemble the syndrome of a central lesion affecting the upper segments of the cervical spinal cord, as this is a common location for syrinx formation. Neurological symptoms in syringomyelia will vary depending on the size, location, and longitudinal extent of the syringomyelic cavity, as well as any associated developmental abnormalities.

Typical Neurological Manifestations of Syringomyelia

Classic neurological manifestations of syringomyelia include:

- Dissociated Sensory Loss: This is a hallmark feature. Patients experience a loss of pain and temperature sensitivity, while tactile (light touch), vibration, and proprioceptive (joint position) senses are often preserved, at least initially. This occurs because the syrinx typically damages the decussating spinothalamic tract fibers carrying pain and temperature information, which cross near the central canal, while sparing the posterior columns carrying touch and proprioception. This sensory loss often occurs in a characteristic "cape-like" distribution over the back of the neck, shoulders, and upper limbs, and can also involve the hands.

- Motor Weakness and Muscle Atrophy: As the syrinx expands and damages anterior horn cells (lower motor neurons), progressive weakness, atrophy, and fasciculations of the muscles can occur. This often affects the muscles of the lower neck, shoulder girdle, arms, and hands. Asymmetric loss of tendon and periosteal reflexes (areflexia or hyporeflexia) in the affected segments is common.

- Spinal Deformity: Scoliosis (sideways curvature of the spine) or kyphoscoliosis (forward and sideways curvature) of the upper thoracic spine can develop, particularly in cases with childhood onset.

- Pain: Chronic pain is a common and often disabling symptom. It can be neuropathic (burning, aching, shooting) in character and may be localized to the neck, shoulders, arms, or back. Coughing, sneezing, or straining can provoke or worsen headache and neck pain, especially in patients with an associated Chiari malformation, due to transient increases in intracranial pressure.

- Autonomic Dysfunction: Symptoms like changes in sweating patterns (hyperhidrosis or anhidrosis), skin trophic changes (smooth, shiny, or thickened skin), and impaired temperature regulation in affected areas can occur.

Symptoms often manifest asymmetrically, with a unilateral decrease in sensitivity being a common early sign. In some patients, pain sensitivity on the face may be reduced due to damage to the descending spinal nucleus and tract of the trigeminal nerve at the level of the upper cervical segments of the spinal cord.

Progression and Complications of Sensory Loss

In idiopathic (primary) cases of syringomyelia, neurological symptoms typically begin in adolescence or young adulthood and tend to progress unevenly, often with periods of stability followed by further deterioration. Some patients with syringomyelia may remain relatively stable for many years and do not become severely disabled, but many experience progressive neurological decline, eventually becoming unable to perform self-care or move independently.

The loss of pain sensitivity (analgesia) in syringomyelia is a significant problem, predisposing patients to unnoticed injuries, burns (often from hot water or objects), and the development of trophic ulcers, particularly on the fingertips and hands. These injuries can become infected and heal poorly.

This axial MRI of the cervical spinal cord demonstrates a syringomyelic cavity located at the level of the C6 vertebral body (indicated by the arrow).

In advanced stages, neurogenic arthropathy (Charcot's joint) can develop in the shoulder, elbow, or less commonly, knee joints. This is a destructive joint disease resulting from impaired pain and position sense. Pronounced weakness in the lower extremities (spastic paraparesis) or increased reflexes (hyperreflexia) often indicates a concomitant abnormality of the cervico-cranial (craniovertebral) junction (e.g., Chiari malformation compressing the brainstem or upper spinal cord) or damage to descending motor tracts.

Syringobulbia: Brainstem Involvement

Syringobulbia is a specific type of syringomyelia where the fluid-filled cavity (syrinx) extends upwards from the cervical spinal cord into the medulla oblongata (lower brainstem) and sometimes the pons. The syringomyelic cavity in syringobulbia usually occupies the lateral parts of the brainstem tegmentum (covering).

Symptoms of syringobulbia reflect damage to cranial nerve nuclei and pathways within the brainstem and can include:

- Paralysis or weakness of the soft palate and vocal cords, leading to dysphagia (difficulty swallowing), nasal regurgitation, and a hoarse or nasal voice.

- Dysarthria (difficulty articulating speech).

- Nystagmus (involuntary eye movements).

- Vertigo (dizziness).

- Atrophy and fasciculations of the tongue (hypoglossal nerve involvement).

- Facial sensory loss (trigeminal nerve involvement).

- Horner's syndrome (ptosis, miosis, anhidrosis) due to involvement of sympathetic pathways.

- Respiratory disturbances in severe cases.

Diagnosis of Syringomyelia

The diagnosis of syringomyelia is established based on characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, and definitively confirmed by neuroimaging studies.

- Clinical Neurological Examination: To identify patterns of sensory loss (especially dissociated sensory loss), motor weakness, reflex changes, and any signs of brainstem dysfunction or associated anomalies.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI of the spinal cord (and brain, if Chiari malformation or syringobulbia is suspected) is the gold standard diagnostic tool. It clearly visualizes the syrinx cavity, its location, extent, and any associated abnormalities like tumors, Chiari malformations, or post-traumatic changes. Cystic cavities are best seen on T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences. Gadolinium contrast may be used if a tumor is suspected.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Myelography: Historically used, a CT scan of the spinal cord performed a few hours after the introduction of a water-soluble contrast agent into the subarachnoid space via lumbar puncture could demonstrate an enlarged cervical spinal cord and opacification of the syrinx cavity. However, MRI has largely replaced CT myelography for diagnosing syringomyelia due to its non-invasive nature and superior soft tissue detail.

- Electrophysiological Studies (EMG/NCS): May show evidence of denervation in affected muscles or slowing of nerve conduction but are not primary diagnostic tools for syringomyelia itself.

- Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis: Usually normal in idiopathic syringomyelia but may show abnormalities (e.g., elevated protein) if associated with a tumor or arachnoiditis.

Given the frequent association of syringomyelia with other congenital malformations, if a syrinx is identified, additional imaging or investigation of the cervico-occipital (craniovertebral) junction is often necessary to look for conditions like Chiari malformations or basilar impression.

Treatment of Syringomyelia

The treatment of syringomyelia is primarily neurosurgical and aims to address the underlying cause of syrinx formation, decompress the syringomyelic cavity if it is causing progressive neurological deficits, and prevent further spinal cord damage. The specific approach depends on the etiology and characteristics of the syrinx.

Neurosurgical Management

The main goals of neurosurgical intervention are to:

- Decompress the Syrinx Cavity: To prevent progressive expansion and further damage to the spinal cord.

- Restore Normal Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Dynamics: If an obstruction to CSF flow is identified (e.g., Chiari malformation, arachnoiditis, tumor), surgery is directed at correcting this obstruction.

- Stabilize or Improve Neurological Function.

Common neurosurgical procedures include:

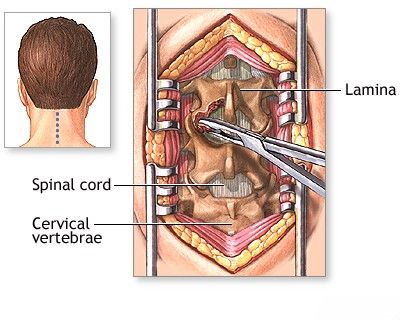

- Foramen Magnum Decompression (Suboccipital Decompression and Cervical Laminectomy): This is the most common surgery for syringomyelia associated with a Chiari I malformation. It involves removing a small portion of the occipital bone (suboccipital craniectomy) and often the lamina of the first cervical vertebra (C1 laminectomy) to create more space for the cerebellum and brainstem, thereby relieving compression at the foramen magnum and restoring normal CSF flow. A dural graft (duraplasty) may be used to further expand the space. The aim is to eliminate the bone window compression of the spinal cord, cerebellum, and medulla oblongata from the occipital bone and vertebral arch. This often leads to collapse or reduction in size of the syrinx.

- Syrinx Shunting Procedures: If direct decompression of an underlying cause is not possible or effective, or for large idiopathic syrinxes, a shunt may be placed to drain fluid from the syrinx cavity into another body cavity. Common shunts include:

- Syringosubarachnoid shunt: Drains syrinx fluid into the surrounding subarachnoid space.

- Syringopleural shunt: Drains syrinx fluid into the pleural cavity (chest).

- Syringoperitoneal shunt: Drains syrinx fluid into the peritoneal cavity (abdomen).

- Tumor Resection: If the syrinx is associated with a spinal cord tumor, surgical removal of the tumor is the primary treatment, which often leads to resolution of the syrinx.

- Untethering of a Tethered Spinal Cord: If syringomyelia is associated with a tethered cord syndrome.

- Arachnoid Lysis and Duroplasty: For post-traumatic or post-inflammatory syringomyelia due to arachnoiditis, surgery may involve lysing (cutting) arachnoid adhesions and expanding the dural space.

Neurosurgeons perform decompression of the syringomyelic cavity in patients with syringomyelia to prevent progressive damage and to decompress the spinal canal in cases where the spinal cord is expanded by the syrinx.

To decompress the spinal cord in patients with syringomyelia (or other conditions causing spinal stenosis), a laminectomy operation is often performed. This procedure involves removing a portion of the vertebral bone (the lamina) to relieve pressure and eliminate compression on the spinal cord.

Conservative and Supportive Care

While surgery is often the mainstay for progressive syringomyelia, conservative management is important for all patients and may be the primary approach for asymptomatic or stable syrinxes:

- Pain Management: Neuropathic pain can be difficult to treat and may require medications such as anticonvulsants (e.g., gabapentin, pregabalin), antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, duloxetine), or other analgesics.

- Physical and Occupational Therapy: To maintain muscle strength, improve mobility, manage spasticity, and adapt to functional limitations.

- Management of Complications: Such as treatment of urinary dysfunction, prevention and care of skin breakdown due to sensory loss, and management of spasticity.

- Regular Neurological Monitoring: Periodic MRI scans and clinical evaluations to monitor syrinx size and neurological status.

- Avoidance of Activities that Increase Intraspinal Pressure: Such as straining, heavy lifting, or activities that could lead to Valsalva maneuver, especially if a Chiari malformation is present.

Differential Diagnosis of Syringomyelia

The symptoms of syringomyelia can mimic other neurological conditions affecting the spinal cord. Differential diagnosis includes:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features from Syringomyelia |

|---|---|

| Spinal Cord Tumors (without syrinx) | May cause progressive myelopathy with motor, sensory, and autonomic dysfunction. MRI will show a solid or cystic tumor mass rather than a simple syrinx cavity (though tumors can cause secondary syrinxes). Contrast enhancement is typical for tumors. |

| Multiple Sclerosis (MS) | Can cause spinal cord lesions (plaques) leading to sensory, motor, and autonomic symptoms. Symptoms often relapsing-remitting. Dissociated sensory loss is less typical. MRI shows characteristic demyelinating plaques in brain and spinal cord. CSF may show oligoclonal bands. |

| Transverse Myelitis | Acute or subacute onset of bilateral motor, sensory (often with a distinct sensory level), and autonomic dysfunction. MRI shows spinal cord inflammation/swelling. Often post-infectious or autoimmune. |

| Spinal Cord Infarction (Ischemic Stroke) | Sudden onset of neurological deficits corresponding to a vascular territory (e.g., anterior spinal artery syndrome). MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging confirms ischemia. |

| Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy | Degenerative changes in the cervical spine (disc herniation, osteophytes, ligamentous hypertrophy) causing spinal cord compression. Symptoms include neck pain, radiculopathy, progressive weakness, spasticity, gait disturbance. MRI shows degenerative changes and cord compression, not typically a syrinx unless secondary. |

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) | Progressive weakness due to degeneration of both upper and lower motor neurons. Sensory system is typically spared. EMG is characteristic. |

| Peripheral Neuropathy (e.g., Diabetic, Hereditary) | Sensory loss, weakness, and reflex changes often in a "glove and stocking" distribution. Primarily affects peripheral nerves, not the spinal cord. EMG/NCS help differentiate. |

Prognosis and Long-Term Management

The prognosis of syringomyelia is variable and depends on the underlying cause, the size and location of the syrinx, the severity of neurological deficits at diagnosis, and the response to treatment. For many patients, especially those with progressive symptoms, syringomyelia is a chronic condition requiring lifelong management and monitoring. Surgical treatment can often stabilize or improve neurological function, particularly if performed before irreversible spinal cord damage occurs. However, neurological deficits may persist, and syrinxes can sometimes recur or enlarge even after surgery. Comprehensive multidisciplinary care involving neurologists, neurosurgeons, physiatrists, physical and occupational therapists, and pain management specialists is often necessary to optimize outcomes and quality of life.

When to Consult a Neurologist or Neurosurgeon

Individuals experiencing symptoms suggestive of syringomyelia should consult a neurologist for evaluation. Symptoms warranting investigation include:

- Unexplained loss of pain and temperature sensation, especially in a cape-like distribution.

- Progressive weakness or atrophy in the arms or hands.

- Chronic pain in the neck, shoulders, or arms.

- Development of scoliosis, particularly in adolescence or adulthood.

- Symptoms associated with Chiari malformation (e.g., headache worsened by coughing/straining, balance problems, swallowing difficulties).

- New neurological symptoms following a spinal cord injury.

If syringomyelia is diagnosed, referral to a neurosurgeon experienced in managing this condition is typically necessary to discuss potential surgical treatment options.

References

- Milhorat TH, Chou MW, Trinidad EM, et al. Chiari I malformation redefined: a clinical and radiographic review of 364 symptomatic patients. Neurosurgery. 1999 May;44(5):1005-17.

- Heiss JD, Snyder K, Peterson MM, et al. Pathophysiology of primary spinal syringomyelia. J Neurosurg Spine. 2012 Nov;17(5):367-80.

- Flanagan EP. Syringomyelia. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;119:485-96.

- Klekamp J. Treatment of syringomyelia. Neurosurg Rev. 2012 Oct;35(4):433-49; discussion 449-50.

- Batzdorf U, McArthur DL, Batzdorf NC. Surgical treatment of Chiari malformation with and without syringomyelia: experience with 177 adult patients. J Neurosurg. 2013 Feb;118(2):232-42.

- Rosso M, Rigamonti A, Lutilizzo G, et al. Syringomyelia: clinical and neuroradiological correlations. Neurol Sci. 2020 Nov;41(11):3111-3119.

- Jordan L, Klinge PM, Koru-Sengul T, et al. Syringomyelia: a practical, evidence-based approach to diagnosis and management. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2022 Jul;33(3):315-325.

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Syringomyelia Fact Sheet. Accessed [Current Date]. (Refer to latest NINDS information)

See also

- Anatomy of the spine

- Ankylosing spondylitis (Bechterew's disease)

- Back pain by the region of the spine:

- Back pain during pregnancy

- Coccygodynia (tailbone pain)

- Compression fracture of the spine

- Dislocation and subluxation of the vertebrae

- Herniated and bulging intervertebral disc

- Lumbago (low back pain) and sciatica

- Osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joint

- Osteocondritis of the spine

- Osteoporosis of the spine

- Guidelines for Caregiving for Individuals with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia

- Sacrodinia (pain in the sacrum)

- Sacroiliitis (inflammation of the sacroiliac joint)

- Scheuermann-Mau disease (juvenile osteochondrosis)

- Scoliosis, poor posture

- Spinal bacterial (purulent) epiduritis

- Spinal cord diseases:

- Spinal spondylosis

- Spinal stenosis

- Spine abnormalities

- Spondylitis (osteomyelitic, tuberculous)

- Spondyloarthrosis (facet joint osteoarthritis)

- Spondylolisthesis (displacement and instability of the spine)

- Symptom of pain in the neck, head, and arm

- Pain in the thoracic spine, intercostal neuralgia

- Vertebral hemangiomas (spinal angiomas)

- Whiplash neck injury, cervico-cranial syndrome