Adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder syndrome)

What is Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder)?

Adhesive capsulitis, commonly known as frozen shoulder, is a condition characterized by significant shoulder pain and progressive stiffness, leading to a marked loss of range of motion in the glenohumeral (shoulder) joint (1, 2). It occurs when the shoulder joint capsule, the strong connective tissue surrounding the joint, becomes thick, tight, and inflamed, sometimes forming restrictive scar tissue (adhesions).

The condition typically develops gradually and has two main features:

- Shoulder Pain: Often a dull or aching pain, felt deep in the shoulder joint, potentially radiating down the arm. It can occur during movement and often worsens at night, disrupting sleep (1, 3).

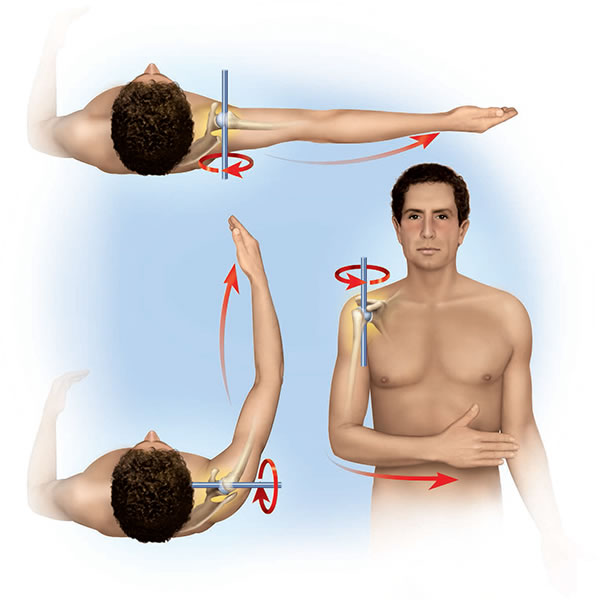

- Stiffness and Loss of Motion (Contracture): A hallmark of frozen shoulder is a significant reduction in both active (patient-initiated) and passive (examiner-assisted) range of motion, particularly affecting external rotation (turning the arm outward) and abduction (lifting the arm out to the side) (2, 4). Difficulty with daily activities like reaching overhead, fastening clothing behind the back (e.g., a bra), or bringing a hand to the mouth becomes increasingly common.

While the term "scapulohumeral periarthrosis" or "periarthritis" has been used historically, "adhesive capsulitis" or "frozen shoulder" are the preferred modern terms, specifically highlighting the involvement of the joint capsule (1).

The onset is often gradual and may initially go unnoticed. Patients, particularly women, might first realize there's a problem when they struggle with tasks requiring internal rotation and adduction, like fastening clothing behind their back (3). In severe stages, the pain and stiffness can significantly impair basic self-care activities.

Sleep disturbance is common due to the inability to find a comfortable position for the affected arm without exacerbating the pain (1).

Stages of Frozen Shoulder

Adhesive capsulitis typically progresses through three distinct stages, although the duration of each stage can vary widely among individuals (1, 2, 5):

- Stage 1: Freezing (Painful Stage)

- Duration: Typically lasts from 6 weeks to 9 months.

- Characteristics: Gradual onset of diffuse, aching shoulder pain. As the pain worsens, range of motion starts to become limited due to pain and early capsular tightening. Pain is often worse at night. Inflammation within the joint capsule is prominent during this stage.

- Stage 2: Frozen (Stiffening Stage)

- Duration: Typically lasts from 4 to 12 months.

- Characteristics: Pain may begin to subside, but stiffness becomes the primary complaint. The shoulder capsule becomes significantly thickened and fibrotic, leading to a marked loss of glenohumeral motion, especially external rotation and abduction. Pain usually occurs only at the extremes of movement.

- Stage 3: Thawing (Resolution Stage)

- Duration: Typically lasts from 6 months to 2 years or longer.

- Characteristics: Gradual, spontaneous improvement in range of motion. Pain continues to decrease. While most patients experience significant recovery, some may have persistent mild stiffness or pain.

The entire process can take 1 to 3 years, or sometimes longer, to resolve fully (1, 5).

Causes and Risk Factors

Adhesive capsulitis can be classified as primary (idiopathic) or secondary:

- Primary (Idiopathic) Adhesive Capsulitis: The cause is unknown. It develops spontaneously without any specific preceding event (1, 2).

- Secondary Adhesive Capsulitis: Develops due to a known cause or associated condition (1, 4).

While the exact cause of the primary form is unclear, several factors are known to increase the risk or are associated with secondary frozen shoulder:

- Age and Sex: Most common between the ages of 40 and 60. Slightly more common in women (1, 3).

- Immobilization or Reduced Mobility: Prolonged inactivity of the shoulder joint after surgery (e.g., mastectomy, cardiac surgery), fracture (e.g., arm fracture), or injury can trigger frozen shoulder (1, 4).

- Systemic Diseases: Certain medical conditions significantly increase the risk:

- Diabetes Mellitus (Type 1 and Type 2): Patients with diabetes have a much higher incidence (10-20% or more) and often experience more severe and prolonged symptoms (1, 2, 6).

- Thyroid Disorders (Hypothyroidism and Hyperthyroidism) (1, 6).

- Cardiovascular Disease (1).

- Parkinson's Disease (1).

- Shoulder Injuries or Surgery: Direct trauma to the shoulder, rotator cuff tears, impingement syndrome, or previous shoulder surgery can sometimes lead to secondary adhesive capsulitis (4).

- Cervical Spine Issues: While less direct, chronic neck problems (e.g., disc herniation causing arm pain and reduced use) could potentially contribute to decreased shoulder mobility, although this is not a primary cause of the capsular pathology itself.

- Repetitive Strain: The original text mentions repetitive activities (guitar playing); while overuse can cause tendinopathies, its direct link to initiating primary adhesive capsulitis is less established than immobility or systemic factors. Pain from overuse leading to reduced motion could be a trigger.

- Hereditary factors are generally not considered a major cause, although some underlying genetic predispositions related to fibrosis or associated diseases might play a minor role.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis is primarily clinical, based on the patient's history and a thorough physical examination (1, 2, 4).

- History: Eliciting details about the gradual onset of pain, progressive stiffness, night pain, difficulty with specific movements, and any relevant risk factors (diabetes, thyroid disease, previous injury, immobilization).

- Physical Examination: The key finding is a significant restriction of *both* active and passive range of motion in the glenohumeral joint. Typically, external rotation (with the arm at the side) is most severely limited, followed by abduction and internal rotation (reaching up the back). The examiner will gently move the patient's arm to assess passive motion limits and feel for the characteristic "hard end-feel" as the tight capsule restricts further movement. Muscle strength is usually normal unless limited by pain or disuse atrophy (1, 4).

Imaging Studies: Often used to rule out other conditions rather than to confirm frozen shoulder, especially in the early stages (1, 4).

- X-rays: Typically normal in primary adhesive capsulitis, showing no significant changes in the articular surfaces or joint space. They are useful for excluding glenohumeral arthritis, calcific tendinitis, or fractures.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) or Ultrasound: Not usually required for diagnosis but may be considered if the diagnosis is uncertain or if other pathology (like a rotator cuff tear) is suspected. Findings suggestive of adhesive capsulitis on MRI can include thickening of the joint capsule (especially in the axillary recess and rotator interval), loss of the normal fat signal around the capsule, and sometimes signs of synovitis (inflammation) or joint effusion, particularly in the early stages (4, 7). However, these findings can be subtle or absent.

Treatment

Treatment for adhesive capsulitis focuses on relieving pain and restoring range of motion and function. It often requires patience and persistence from both the patient and the medical team, as recovery can be slow (1, 2, 8).

A multi-modal approach is typically employed, often starting with conservative measures:

- Pain and Inflammation Control:

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Medications like ibuprofen or naproxen can help reduce pain and inflammation, particularly in the freezing stage (1, 8).

- Corticosteroid Injections: Intra-articular injection of corticosteroids directly into the glenohumeral joint can provide significant short-to-medium term pain relief and reduce inflammation, facilitating physical therapy. Often most effective in the early, painful (freezing) stage (1, 2, 8). Subacromial injections (as shown in one image) target bursitis or impingement, which may co-exist but are less specific for the capsular pathology of frozen shoulder itself; intra-articular is preferred for adhesive capsulitis (1).

- Physical Therapy and Stretching: This is the cornerstone of treatment. A physical therapist guides the patient through specific, gentle stretching exercises designed to gradually increase range of motion and stretch the tightened joint capsule. Consistency and patience are crucial. Exercises often include pendulum swings, passive external rotation stretches, fingertip wall climbs, and cross-body stretches (1, 2, 8). Overly aggressive stretching, especially in the freezing stage, can worsen pain and inflammation.

- Other Modalities:

- Heat or cold application can provide temporary pain relief.

- Manual therapy techniques performed by a therapist may help mobilize the joint and soft tissues (1).

- Physiotherapy modalities like Ultrasound or Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) might be used adjunctively for pain control, although evidence for their specific benefit in altering the disease course is limited (1).

- More Invasive Procedures (if conservative treatment fails after several months):

- Hydrodilatation (Distension Arthrography): Injecting a large volume of sterile saline, sometimes mixed with corticosteroid and local anesthetic, into the joint capsule under imaging guidance (fluoroscopy or ultrasound) to stretch or rupture the tight capsule (1, 9).

- Manipulation Under Anesthesia (MUA): The patient is put under general anesthesia, and the surgeon forcefully moves the shoulder through its full range of motion to break up adhesions and stretch the capsule. Usually followed by intensive physical therapy (1, 2).

- Arthroscopic Capsular Release: A minimally invasive surgical procedure where an arthroscope (a small camera) and specialized instruments are inserted into the shoulder joint. The surgeon visually identifies and cuts (releases) the thickened, tight portions of the joint capsule, allowing for improved motion (1, 2, 10). Often combined with gentle manipulation.

Without active treatment, frozen shoulder can lead to prolonged disability and potentially permanent loss of motion (ankylosis is rare but significant stiffness can persist). Early diagnosis and consistent adherence to treatment, especially physical therapy, are key to achieving the best outcome (1, 8).

Differential Diagnosis

It's important to differentiate adhesive capsulitis from other causes of shoulder pain and stiffness:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Rotator Cuff Tear/Tendinopathy | Pain often worse with active movement, especially overhead or against resistance. Passive range of motion may be normal or only mildly limited (unless pain-inhibited). Weakness on specific muscle testing is common with tears. Diagnosis aided by ultrasound or MRI (4). |

| Subacromial Impingement Syndrome/Bursitis | Pain typically occurs within a specific arc of motion (painful arc) during active abduction. Passive motion is usually full, though may be painful. Positive impingement signs on examination. Often responds well to subacromial corticosteroid injection (as shown in gallery-6 image) (1). |

| Glenohumeral Osteoarthritis | Chronic, progressive pain and stiffness. Crepitus (grinding sensation) may be present. X-rays show characteristic joint space narrowing, osteophytes (bone spurs), and sclerosis. Loss of motion affects both active and passive ranges but may differ in pattern from frozen shoulder (1). |

| Calcific Tendinitis | Can cause severe, acute shoulder pain. X-rays show calcium deposits within the rotator cuff tendons. Range of motion may be limited due to acute pain, but passive motion might be less restricted globally than in frozen shoulder once pain is controlled. |

| Cervical Radiculopathy | Pain radiating from the neck down the arm, often associated with numbness, tingling, or weakness in a specific nerve root pattern. Neck movements may provoke symptoms. Shoulder range of motion itself is typically normal, although pain may limit active movement. Neurological examination findings are key. |

| Acromioclavicular (AC) Joint Arthritis | Pain localized to the top of the shoulder (AC joint). Pain often worse with cross-body adduction or reaching overhead. Glenohumeral joint motion usually preserved. |

References

- Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S, et al. Management of frozen shoulder: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(11):1-264. doi:10.3310/hta16110

- Neviaser AS, Neviaser RJ. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19(9):536-542. doi:10.5435/00124635-201109000-00004

- Dias R, Cutts S, Massoud S. Frozen shoulder. BMJ. 2005;331(7530):1453-1456. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7530.1453

- Le HV, Lee SJ, Nazarian A, Rodriguez EK. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: review of pathophysiology and current clinical treatments. Shoulder Elbow. 2017;9(2):75-84. doi:10.1177/1758573216676786

- Reeves B. The natural history of the frozen shoulder syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 1975;4(4):193-196. doi:10.3109/03009747509100188

- Tighe CB, Oakley Jr WS. Adhesive Capsulitis. [Updated 2023 Aug 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532955/

- Suh CH, Yun SJ, Jin W, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging features for diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. Eur Radiol. 2019;29(2):566-577. doi:10.1007/s00330-018-5547-3

- Page MJ, Green S, Kramer S, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8):CD011275. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011275

- Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV. Arthrographic distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD007005. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007005

- Grant JA, Schroeder N, Miller BS, Carpenter JE. Comparison of manipulation and arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22(8):1135-1145. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2013.04.004

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone