Ankle and foot sprain

Ankle & Foot Sprain Overview

An ankle sprain is one of the most common musculoskeletal injuries [1]. It occurs when the ligaments supporting the ankle joint are stretched beyond their normal range, leading to partial or complete tears [1]. The most frequent mechanism is an inversion injury, where the foot rolls inward ("podvertyvanie" or twisting inward), stretching or tearing the lateral ligaments (primarily the anterior talofibular ligament - ATFL, followed by the calcaneofibular ligament - CFL) [1, 2]. Eversion injuries (foot rolling outward) are less common and affect the medial deltoid ligament [1].

These injuries often happen during sports activities involving jumping, cutting, or sudden changes in direction, but they can also occur during simple activities like walking on uneven surfaces, stepping off a curb awkwardly, or slipping on ice [1].

Ankle & Foot Sprain Diagnosis

Diagnosing an ankle or foot sprain involves a combination of clinical assessment and sometimes imaging [1].

Clinical Signs & Symptoms [1, 2]:

- Pain: Localized pain, particularly upon palpation over the injured ligaments (e.g., anterior to the lateral malleolus for ATFL sprains).

- Mechanism Reproduction: Increased pain when the foot is passively moved in the direction that mimics the injury mechanism (e.g., inversion for lateral sprains).

- Swelling (Edema): Localized swelling around the affected malleolus or more diffuse ankle swelling.

- Bruising (Ecchymosis): May appear hours to days after the injury, often tracking down towards the heel and toes.

- Hemarthrosis: Bleeding directly into the ankle joint cavity, causing a more diffuse, boggy swelling, particularly noticeable in the anterolateral aspect of the joint. Fluctuation (a wave-like feeling on palpation) may be present.

- Instability: A feeling of the ankle "giving way," particularly with more severe sprains (Grade II or III involving complete tears). Clinical tests like the anterior drawer test (for ATFL) and talar tilt test (for CFL) assess ligamentous laxity, although acute pain and swelling can limit their reliability.

- Audible Pop/Snap: Patients may report hearing or feeling a "pop" or "crack" at the time of injury, often indicating a significant ligament tear (Grade II or III).

Differential Diagnosis of Ankle/Foot Pain After Injury [1, 3]

| Condition | Key Features / Distinguishing Points | Typical Provocative Tests / Findings / Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Ankle Sprain (Lateral) | Inversion injury. Pain/swelling/tenderness over lateral ligaments (ATFL, CFL). | Pain with inversion. Positive anterior drawer/talar tilt (if severe/assessable). X-rays negative for fracture (if Ottawa rules met). |

| Ankle Fracture (Malleolar, Talar, Calcaneal) | Often higher energy mechanism. Point tenderness directly over bone. Inability to bear weight (often). Gross deformity may be present. | Bony tenderness (Ottawa rules positive). X-rays confirm fracture. CT for complex fractures. |

| 5th Metatarsal Base Fracture (e.g., Jones) | Often occurs with inversion injury. Pain/swelling localized to base of 5th metatarsal. | Point tenderness over 5th metatarsal base (Ottawa rules positive). X-rays confirm fracture. |

| Syndesmotic Sprain (High Ankle Sprain) | Mechanism often involves external rotation/dorsiflexion. Pain located higher, between tibia and fibula (anterior or posterior tibiofibular ligaments). Prolonged recovery common. | Positive squeeze test, external rotation stress test. Tenderness over syndesmosis. X-rays may show widening; MRI confirms ligament injury. |

| Peroneal Tendon Injury (Tear, Subluxation/Dislocation) | Pain/swelling posterior to lateral malleolus. May have clicking/snapping sensation (subluxation). Pain with resisted eversion. | Tenderness along peroneal tendons. Pain/weakness with resisted eversion. Apprehension/subluxation with specific maneuvers. Ultrasound or MRI confirms tendon pathology. |

| Osteochondral Lesion of Talus (OCL/OCD) | Deeper ankle pain, may have catching/locking. Often history of previous sprain(s). Persistent pain after sprain treatment. | Variable tenderness. X-rays may show lesion (esp. later stages). MRI is diagnostic. |

| Subtalar Joint Sprain/Injury | Pain often felt deeper or slightly inferior to lateral malleolus. Difficulty walking on uneven ground. Often occurs with severe inversion. | Tenderness over sinus tarsi. Pain with passive subtalar motion (inversion/eversion). Diagnosis often clinical or via MRI. |

| Achilles Tendon Injury | Pain localized to posterior heel/tendon. Weakness with plantarflexion (push-off). May feel gap if ruptured. | Tenderness over Achilles. Positive Thompson test (rupture). Ultrasound or MRI confirms. |

Imaging like Computed Tomography (CT) provides detailed views of bone structures, useful for identifying associated fractures, but less ideal for primary ligament assessment compared to MRI [3]. (Video depicts CT usage).

Diagnostic Procedures [1, 3]:

- Physical Examination: Assessing tenderness, swelling, range of motion, stability (if tolerated), and neurovascular status.

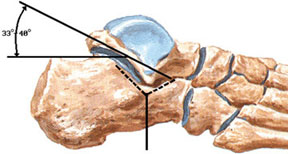

- X-rays: Crucial, especially if the patient meets the Ottawa Ankle Rules criteria (inability to bear weight, bone tenderness at specific points), to rule out associated fractures (malleoli, talus, calcaneus, 5th metatarsal base). Stress X-rays are sometimes used to assess instability but are less common acutely.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Not typically needed for routine acute sprains but useful for evaluating chronic instability, suspected syndesmotic (high ankle) sprains, osteochondral lesions (cartilage/bone damage), peroneal tendon injuries, or if symptoms persist despite appropriate conservative treatment. Provides excellent visualization of ligaments and soft tissues.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: Primarily used to better define complex fractures identified on X-ray or to assess for subtle fractures or tarsal coalitions.

- Ultrasound: Can be used dynamically to assess ligament integrity and associated tendon pathology.

Sprains are typically graded based on severity [1]:

- Grade I: Mild stretching of ligaments, minimal swelling/tenderness, no instability.

- Grade II: Partial tearing of ligaments, moderate pain, swelling, tenderness, mild-to-moderate instability.

- Grade III: Complete tearing of ligaments, severe pain, swelling, tenderness, significant instability.

Ankle & Foot Sprain Treatment

Treatment depends on the severity (grade) of the sprain [1].

Mild Sprains (Grade I):

- RICE Protocol: Rest, Ice (apply cold packs 15-20 minutes several times daily), Compression (using an elastic bandage like an 8-shaped wrap), Elevation (keeping the ankle above heart level).

- Activity Modification: Avoid activities that cause pain.

- Early Mobilization: Gentle range-of-motion exercises as pain allows.

- Support: A compression bandage or soft ankle support.

- Return to normal activity typically within 1-2 weeks.

Moderate to Severe Sprains (Grade II & III):

- RICE Protocol: As above, potentially for a longer duration.

- Immobilization: Required to protect the healing ligaments. Options include:

- Removable walking boot

- Air-stirrup brace

- Lace-up ankle support

- Short leg cast (less common now, used for severe instability or non-compliance)

- Weight-Bearing: Often partial or non-weight-bearing initially (using crutches), progressing as tolerated.

- Physical Therapy/Rehabilitation: Crucial for recovery. Starts once pain and swelling subside. Includes:

- Range-of-motion exercises

- Strengthening exercises (especially peroneal muscles for lateral stability)

- Proprioceptive and balance training (essential to prevent recurrence)

- Activity-specific training

- Pain Management: NSAIDs for pain and inflammation.

- Aspiration: If significant hemarthrosis causes severe pain or pressure, aspiration (draining the blood with a needle) may be considered, though not routinely done.

- Physical Therapy Modalities: Ultrasound (UHF), electrical stimulation (SMC), laser therapy, heat (after the acute phase), or whirlpool baths may be used to manage pain, swelling, and promote healing.

- Therapeutic Injections: Injections (block) of local anesthetic (like novocaine or lidocaine), sometimes combined with corticosteroids (like hydrocortisone), into the most painful areas around the ligaments may provide temporary relief for persistent pain, but routine corticosteroid use is debated due to potential effects on ligament healing.

Recovery time for Grade II/III sprains is longer, ranging from several weeks to several months [1]. Full return to sports may take 2-4 months or more [1].

Additional Treatment Considerations:

- Manual Therapy: Joint mobilization techniques may be used during rehabilitation to restore normal joint mechanics [1].

- Surgery: Rarely indicated for acute lateral ankle sprains [1]. May be considered for [1, 2]:

- Severe syndesmotic (high ankle) sprains with instability.

- Associated injuries requiring surgery (e.g., large osteochondral defects, significant peroneal tendon tears).

- Chronic ankle instability unresponsive to prolonged conservative treatment and rehabilitation (involves ligament reconstruction).

Proper rehabilitation is key to preventing chronic ankle instability and recurrent sprains [1].

References

- Waterman BR, Owens BD, Davey S, Zacchilli MA, Belmont PJ Jr. The epidemiology of ankle sprains in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010 Oct 6;92(13):2279-84. (Or similar epidemiological review).

- Skinner HB, McMahon PJ. Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Orthopedics. 5th ed. McGraw Hill; 2014. Chapter 9: Foot & Ankle Trauma.

- Stiell IG, McKnight RD, Greenberg GH, et al. Implementation of the Ottawa ankle rules. JAMA. 1994 Mar 16;271(11):827-32.

- Drake RL, Vogl W, Mitchell AWM. Gray's Anatomy for Students. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Chapter 6: Lower Limb (Section on Ankle and Foot).

See also

- Achilles tendon inflammation (paratenonitis, ahillobursitis)

- Achilles tendon injury (sprain, rupture)

- Ankle and foot sprain

- Arthritis and arthrosis (osteoarthritis):

- Autoimmune connective tissue disease:

- Bunion (hallux valgus)

- Epicondylitis ("tennis elbow")

- Hygroma

- Joint ankylosis

- Joint contractures

- Joint dislocation:

- Knee joint (ligaments and meniscus) injury

- Metabolic bone disease:

- Myositis, fibromyalgia (muscle pain)

- Plantar fasciitis (heel spurs)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)

- Vitamin D and parathyroid hormone