External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

Understanding Nasal Furunculosis (Nose Boil)

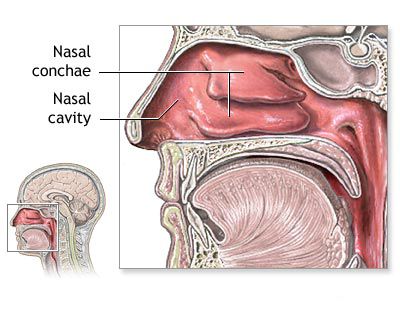

Nasal furunculosis, commonly known as a nose boil, is an acute, localized pyogenic (pus-forming) inflammation of a hair follicle and its associated sebaceous gland, typically occurring in the skin of the nasal vestibule (the entrance of the nostril) or on the external nose. This condition can be particularly painful and carries a risk of serious complications due to the venous drainage patterns of the face.

Causes and Predisposing Factors

Nasal furunculosis frequently develops in individuals with compromised immune systems, those suffering from generalized furunculosis (recurrent boils elsewhere on the body), or those with certain systemic conditions like diabetes mellitus or enteric diseases. In children, conditions such as exudative diathesis or rickets can predispose them to such infections. Several local factors can also increase the risk:

- Habitual nose-picking: Introduces bacteria into the nasal vestibule.

- Squeezing blackheads or pimples: Can traumatize the skin and spread infection.

- Frequent acute respiratory infections or sinusitis: Can lead to persistent nasal discharge and skin irritation.

- Pre-existing skin diseases: Conditions like eczema can compromise the skin barrier.

- Nasal hair plucking: Can create micro-trauma and open pathways for infection.

The most common causative pathogen for nasal furunculosis is *Staphylococcus aureus*. This bacterium invades the sebaceous glands or hair follicles, leading to an intense inflammatory reaction. The typical locations for a nasal furuncle include the wings of the nose (alae nasi), the nasal vestibule, the skin of the upper lip, and the nasolabial folds. This area is sometimes referred to as the "danger triangle" of the face due to its venous connections to the cavernous sinus within the brain.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Nasal Furunculosis

The clinical course and severity of nasal furunculosis can vary:

- Mild Cases: In the initial 1-2 days, there is localized redness (erythema), slight swelling (edema), and tenderness at the site of infection. The patient's general condition may be minimally affected, with normal or slightly elevated (subfebrile) body temperature. By the 3rd or 4th day, a central pustule or "head" (the necrotic core or rod) may form. Spontaneous or careful drainage of this core typically leads to resolution and recovery. Sometimes, the process may only reach the stage of infiltration and then resolve without forming a distinct core (abortive furuncle).

- Severe Cases: Characterized by a more pronounced and painful, indurated (hardened) infiltration. Significant soft tissue edema can extend beyond the immediate area of the nose to involve the cheeks, upper lip, and even the lower (and sometimes upper) eyelid on the affected side. The patient's general condition deteriorates, with high fever, loss of appetite, and headache. Regional lymph nodes (submandibular, preauricular) may become enlarged and tender. Children may become irritable and whiny. Blood tests (complete blood count) often show leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count, e.g., up to 15.0 x 109/L) and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, e.g., up to 35 mm/h), indicating significant inflammation.

Diagnosis and Potential Complications of Nasal Furunculosis

The diagnosis of nasal furunculosis is usually straightforward based on the clinical appearance and history. However, it's important to differentiate it from other conditions such as an abscess of the nasal septum, a suppurating cyst on the nasal dorsum, acute ethmoiditis (especially if periorbital swelling is present), or periostitis of the upper jaw.

The primary concern with nasal furunculosis is the risk of serious, even life-threatening, complications due to the unique venous drainage of the mid-face. Veins in this "danger triangle" (angular vein, facial veins) have connections with the ophthalmic veins, which drain directly into the cavernous sinus within the skull. This allows infections to potentially spread intracranially. Potential complications include:

- Angular vein phlebitis or thrombosis: Inflammation or clotting of the angular vein.

- Thrombophlebitis of other facial veins: Affecting veins of the orbit, upper lip, cheeks, forehead, or jaw area.

- Orbital cellulitis or phlegmon: Diffuse inflammation or infection of the orbital tissues.

- Subperiosteal abscess of the orbit: Collection of pus beneath the periosteum lining the orbit.

- Retrobulbar abscess: Abscess behind the eyeball.

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis: A critical condition involving a blood clot in the cavernous sinus, often leading to severe neurological deficits and high mortality if not treated urgently.

- Meningitis: Inflammation of the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord.

- Brain abscess: Localized collection of pus within the brain tissue.

The risk of these intracranial complications is particularly high with furuncles located in the nasal vestibule due to the direct venous pathways. Other systemic complications can include pneumonia, sepsis (bloodstream infection), and, rarely, kidney involvement.

Treatment of Nasal Furunculosis

Treatment strategies depend on the severity of the infection:

- Mild Cases:

- Oral antibiotics effective against *Staphylococcus aureus* (e.g., cephalexin, dicloxacillin, or clindamycin if MRSA is suspected). Sulfonamides like Sulfadimethoxine were historically used.

- Topical antibiotic ointments (e.g., mupirocin, fusidic acid) applied to the lesion and into the nostrils to reduce bacterial carriage.

- Warm compresses applied to the affected area can promote drainage and relieve pain.

- Hyposensitizing drugs (antihistamines like diphenhydramine, suprastin, pipolfen), calcium supplements (chloride or gluconate), and vitamins may be considered supportive.

- Severe Cases or Signs of Spreading Infection:

- Systemic antibiotics, often administered intravenously initially, are crucial. Higher doses may be required.

- Hospitalization may be necessary for close monitoring and IV therapy.

- Plasma transfusion (historically at 5-10 ml per 1 kg body weight) was sometimes used in severe pediatric cases.

- Immunobiological preparations like staphylococcal toxoid or antifagin were historically employed to boost immunity (e.g., in school-age children, initial dose 0.2 ml, increased by 0.1 ml every 3 days for 3-10 injections). Modern immunotherapy approaches are different.

- Autohaemotherapy (re-injecting the patient's own blood, 2-6 ml every other day) was a historical supportive measure.

- Supportive care including desensitizing agents, dehydration therapy (if needed), and detoxification (e.g., magnesium, glucose infusions).

- Proteolytic enzymes, anabolic hormones, and anticoagulants (heparin, fibrinolysin) have been mentioned in older literature but are not standard current practice for uncomplicated furunculosis.

To prevent auto-infection and spread, the surrounding skin should be kept clean and may be wiped with an antiseptic solution like boric, salicylic, or camphor alcohol. Physiotherapy modalities such as local ultraviolet irradiation (UVI), high-frequency currents (UHF), or Solux lamp therapy may be prescribed in some settings to promote healing.

Crucially, manipulating the furuncle (squeezing, pressing, or attempting to incise it prematurely) is strictly contraindicated, especially in the "danger triangle" area, as this can force bacteria into the bloodstream and increase the risk of severe complications. Incision and drainage should only be performed by a healthcare professional if a clear, fluctuant abscess has formed and is ready to drain.

In infants, hands should be gently immobilized (e.g., with mittens) to prevent scratching or traumatizing the boil. If furunculosis is recurrent or persistent, the patient should be evaluated for underlying conditions such as diabetes mellitus, immunodeficiency, or tuberculosis.

Nasal Eczema (Atopic Dermatitis of the Nose)

Characteristics and Triggers

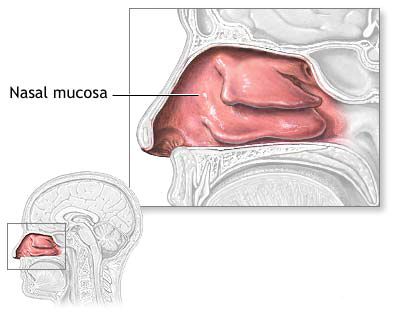

Nasal eczema, a form of atopic dermatitis affecting the skin of the nasal vestibule and external nose, is characterized by diffuse redness (hyperemia), swelling (edema), oozing (weeping) vesicles, and intense itching (pruritus). The skin may become dry, scaly, and cracked in chronic stages. This condition often extends from facial eczema or may be associated with eczema elsewhere on the body, particularly the scalp. It is frequently seen in individuals with an atopic diathesis (a genetic predisposition to allergic diseases like asthma, hay fever, and eczema). Coexisting conditions such as chronic rhinitis, rhinosinusitis, or the presence of a foreign body in the nasal cavity can exacerbate nasal eczema due to persistent nasal discharge and irritation. Habits like picking crusts from the nose with fingers, frequent wiping, or forceful nose blowing can further traumatize the delicate skin, spread infection, and worsen the eczema.

Treatment Approaches for Nasal Eczema

Management of nasal eczema often requires a collaborative approach with a dermatologist:

- Identification and Elimination of Triggers: Efforts should be made to identify and avoid potential irritants or allergens contributing to the eczema. This may involve allergy testing.

- Dietary Management: A rational diet, sometimes involving restriction of common allergenic foods or those known to exacerbate eczema (e.g., certain carbohydrates and proteins, processed foods), may be beneficial, especially in children.

- Topical Therapies:

- Emollients: Frequent application of bland, fragrance-free emollients or indifferent oils helps to hydrate and protect the skin.

- Topical Corticosteroids: Low to mid-potency topical corticosteroids (e.g., hydrocortisone, or combination products like Oxycort which contains oxytetracycline and hydrocortisone) are used to reduce inflammation and itching during flare-ups. Prolonged use on the face should be cautious and under medical supervision.

- Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors: Pimecrolimus cream or tacrolimus ointment can be effective alternatives to corticosteroids, especially for long-term management or sensitive areas, as they do not cause skin atrophy.

- Pastes and Powders: Zinc-containing pastes can have a soothing and drying effect.

- Antiseptic or Antibiotic Creams: If secondary bacterial infection is suspected, topical antibiotics (e.g., mupirocin, fusidic acid) may be prescribed.

- Wet Dressings: For acutely weeping forms of eczema, lotions or wet dressings with a 1% resorcinol solution or other astringents can provide a drying and soothing effect.

- Systemic Treatment: In severe cases, oral antihistamines may be used to reduce itching, and short courses of systemic corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants might be considered under specialist care.

- Management of Underlying Nasal Conditions: Treating any coexisting rhinitis or sinusitis is important to reduce nasal discharge and irritation.

Nasal Sycosis (Folliculitis of Nasal Hairs)

Etiology and Presentation

Nasal sycosis, also known as sycosis barbae when affecting the beard area but applicable to the nasal vestibule, is a chronic, deep-seated purulent inflammation of the hair follicles (folliculitis) and surrounding perifollicular tissue within the vestibule of the nose. It typically presents as multiple, small, itchy or painful pustules pierced by hairs, or as reddish, indurated papules. The lesions can coalesce to form larger, crusted plaques. A similar process may coexist on the upper lip or chin. The primary causative agent is usually *Staphylococcus aureus*. Less commonly, fungal infections, such as those caused by *Trichophyton* species (parasitic sycosis, often acquired from infected animals like dogs and cats), can be responsible. It is also important to exclude demodicosis (infestation by *Demodex* mites) as a potential contributing or mimicking factor.

Treatment of Nasal Sycosis

Management of nasal sycosis aims to eradicate the infection and prevent recurrence:

- Topical Antibiotics: Ointments or creams containing antibiotics like mupirocin, fusidic acid, or bacitracin are applied directly to the affected areas.

- Systemic Antibiotics: In more extensive or resistant cases, oral antibiotics effective against staphylococci (e.g., cephalexin, dicloxacillin, clindamycin) may be prescribed for several weeks.

- Antifungal Therapy: If a fungal infection is confirmed, topical or systemic antifungal medications will be necessary.

- Hair Removal (Epilation): Careful removal of hairs from infected follicles can sometimes aid drainage and resolution, though this should be done gently to avoid further trauma.

- Antiseptic Cleansers: Washing the area with mild antiseptic cleansers can help reduce bacterial load.

- Warm Compresses: May help soothe discomfort and promote drainage of pustules.

- Restorative or Supportive Therapy: Addressing any underlying immune deficiencies or predisposing factors.

- Emollient Ointments: After the acute infection subsides, emollients can help soothe the skin.

Treatment can be prolonged, and recurrences are common if predisposing factors are not addressed.

Nasal Erysipelas

Causes and Clinical Features

Nasal erysipelas is an acute superficial bacterial infection of the skin (a type of cellulitis) that specifically affects the dermis and superficial lymphatics, characterized by a sharply demarcated, raised, erythematous (red), warm, and tender area of skin. The primary etiological agent is usually *Streptococcus pyogenes* (Group A Streptococcus). Predisposing factors include any breaks in the skin barrier, such as cracks, fissures, abrasions, or minor injuries in the nasal vestibule or on the external nose, which allow bacteria to enter. The infection typically starts with a rapidly spreading area of redness and infiltration around the anterior part of the nose. The patient often experiences systemic symptoms, including high fever (up to 40°C or 104°F), chills, malaise, and headache. The affected nasal mucous membrane may also show hyperemia, swelling, and tenderness. In the bullous form of erysipelas, blisters (bullae) containing serous or seropurulent fluid may develop on the inflamed skin. Occasionally, the inflammatory process can involve the paranasal sinuses. Erysipelas often has a tendency to spread outwards from the initial site, potentially affecting larger areas of the face around the nose.

Treatment of Nasal Erysipelas

Prompt treatment is essential to prevent spread and complications:

- Systemic Antibiotics: Penicillin (or amoxicillin) is the drug of choice for streptococcal infections. For penicillin-allergic patients, alternatives like macrolides (e.g., erythromycin, clarithromycin) or clindamycin are used. Antibiotics are typically given for 10-14 days. Severe cases may require intravenous administration.

- Supportive Care: Bed rest, adequate hydration, and analgesics/antipyretics for pain and fever.

- Local Care: Keeping the affected area clean. Cool compresses may provide symptomatic relief. Topical antibiotics are generally not sufficient as the infection is deeper.

- Elevation: If significant swelling is present, elevating the affected part (if possible) can help reduce edema.

- Physiotherapy: Nasal ultraviolet irradiation (UVI) was historically mentioned as an adjunctive therapy.

- General Restorative Therapy: Supporting the patient's overall health.

Streptocide (a sulfonamide) was a historical treatment but has largely been replaced by more effective antibiotics.

Nasal Frostbite

Pathophysiology and Predisposition

Nasal frostbite is a localized tissue injury caused by exposure to freezing temperatures. It occurs when body tissues freeze, leading to ice crystal formation within cells and extracellular spaces, cellular dehydration, and damage to blood vessels. The nose, along with ears, fingers, and toes, is particularly susceptible due to its exposed position and relatively limited blood supply compared to core body areas. Frostbite is more common in individuals who are debilitated, anemic, or have conditions that impair peripheral circulation. Children are also at higher risk due to their smaller body mass and potentially less awareness of early symptoms.

There are typically four recognized grades of frostbite severity:

- Grade I (Frostnip): Superficial freezing without tissue loss. Characterized by numbness, pallor, and subsequent redness, swelling, and tingling upon rewarming.

- Grade II: Superficial skin freezing with blister formation (clear or milky fluid) within 24-48 hours, surrounded by erythema and edema. Deeper tissues remain unharmed.

- Grade III: Deep freezing involving the full thickness of the skin and extending into the subcutaneous tissue. Hemorrhagic blisters (blood-filled) may form, followed by the development of a hard, black eschar (dead tissue). Underlying tissue remains viable.

- Grade IV: Deep tissue freezing involving skin, muscle, tendon, and bone, leading to complete tissue necrosis, mummification, and eventual autoamputation if not surgically debrided.

Symptoms of Nasal Frostbite

The initial symptoms of nasal frostbite can be subtle:

- Early Stage (Frostnip): The skin of the tip or wings of the nose may appear unusually pale or waxy (blanching). There might be a sensation of coldness, numbness, tingling, or slight prickling pain, which children, in particular, may not notice or report.

- Progressive Freezing: As cooling continues, the affected skin becomes completely insensitive (numb) and may turn a bluish-red or mottled color before becoming hard and white. It is typically painless at this stage.

- Upon Rewarming: As the tissue thaws, intense pain, burning sensations, throbbing, swelling, redness, and blister formation (depending on the grade) can occur.

Treatment of Nasal Frostbite

Proper management of nasal frostbite is crucial to minimize tissue damage and prevent long-term complications:

- Remove from Cold: Immediately move the person to a warm environment.

- Gentle Rewarming: Rapid rewarming is key. Immerse the frostbitten area in warm water (not hot, typically 37-39°C or 98.6-102.2°F) for 15-30 minutes or until the skin becomes soft and sensation returns. Avoid dry heat (like radiators or fires) as it can cause burns. Do NOT rub the frostbitten area with snow or massage it, as this can cause further tissue damage.

- Pain Management: Rewarming can be very painful; analgesics (e.g., ibuprofen, acetaminophen, or stronger pain relievers if needed) should be administered.

- Protect from Refreezing: Once thawed, the tissue is extremely vulnerable to refreezing, which causes more severe damage.

- Blister Care: Clear blisters may be left intact or debrided by a medical professional. Hemorrhagic blisters are often left intact initially. Topical aloe vera or antibiotic ointments (e.g., Oxycort - oxytetracycline+hydrocortisone) may be applied.

- Tetanus Prophylaxis: Ensure tetanus immunization is up to date.

- Systemic Anti-inflammatory Treatment: In severe cases, general and local anti-inflammatory treatments may be employed. This might include NSAIDs.

- Medical Evaluation: All cases of frostbite beyond mild frostnip should be evaluated by a healthcare professional to assess the severity and guide further treatment, which may include hospitalization for severe grades, wound care, antibiotics if infection develops, or surgical debridement of necrotic tissue later on.

- Avoid Smoking: Nicotine constricts blood vessels and can impair healing.

For Grade I frostbite, topical heat (warm compresses, not direct heat) and gentle rubbing with alcohol were historical mentions, but rapid water rewarming is now standard. Formed blisters (Grade II) may be revealed (debrided) under sterile conditions by a medical professional if they are large or tense.

Differential Diagnosis of Painful Nasal Skin Lesions

When a patient presents with a painful lesion on or in the nose, several conditions need to be considered:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Nasal Furunculosis | Localized, tender, erythematous nodule or pustule at a hair follicle; may have a central core; risk of cavernous sinus thrombosis. |

| Herpes Simplex (Cold Sore) | Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, often preceded by prodromal tingling or burning; typically recurrent in the same location. Can occur on nasal tip or vestibule. |

| Impetigo | Superficial bacterial infection, often staphylococcal or streptococcal; presents as vesicles or pustules that rupture to form characteristic honey-colored crusts. More common in children. |

| Nasal Vestibulitis | Diffuse inflammation, redness, crusting, and tenderness at the nasal entrance; often bilateral; may be due to chronic irritation, nose picking, or infection. |

| Cellulitis/Erysipelas | Spreading area of redness, warmth, swelling, and tenderness; erysipelas has sharply demarcated borders; systemic symptoms (fever, malaise) are common. |

| Acute Allergic Reaction (e.g., Angioedema) | Sudden onset of swelling, often with itching or urticaria; may affect lips, eyelids, and nose. Usually not as localized or pustular as furunculosis. |

| Insect Bite | Localized swelling, redness, itching, and a central punctum may be visible. |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma or Basal Cell Carcinoma | Persistent, non-healing sore, ulcer, or nodule; may bleed easily; typically slower growing. More common in sun-exposed areas. Biopsy needed for diagnosis. |

When to Seek Medical Attention for External Nose Diseases

It's important to seek medical attention from an ENT specialist or dermatologist for external nose conditions if you experience:

- A painful, red, swollen lump on or in the nose that is worsening or not improving after a few days (suspicion of furunculosis).

- Signs of spreading infection: increasing redness, warmth, swelling extending to the face or around the eyes.

- Fever, chills, or feeling generally unwell associated with a nasal skin lesion.

- Recurrent nasal boils or skin infections.

- Persistent nasal eczema or sycosis that doesn't respond to over-the-counter treatments.

- A sharply demarcated, rapidly spreading red rash on the nose and face (suspicion of erysipelas).

- Any suspected frostbite, especially if blistering occurs or there is loss of sensation.

- A non-healing sore, ulcer, or new growth on the nose.

- Concerns about potential complications or severe pain.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment can prevent complications and lead to quicker recovery.

References

- Brook I. Microbiology and management of skin and soft tissue infections. Wounds. 2005;17(1):23-35. (General context for bacterial skin infections)

- Stulberg DL, Penrod MA, Blatny RA. Common bacterial skin infections. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Jul 1;66(1):119-24. (Covers furuncles, erysipelas)

- Bikowski J. Facial Erysipelas. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(9):956.

- Leung AKC, Barankin B, Hon KLE. Atopic Dermatitis: An Overview. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2017;11(1):2-22. (Context for eczema)

- Hay RJ, Baran R. Fungal infections of the skin and nails (tinea). In: Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C, editors. Rook's Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. p. 32.1-32.88. (Context for fungal sycosis)

- Imray CHE, Grieve A, Dhillon S, The Caudwell Xtreme Everest Research Group. Cold damage to the extremities: frostbite and non-freezing cold injuries. Postgrad Med J. 2009;85(1007):481-488.

- Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016. (General dermatology reference for conditions like furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas)

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis