Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Understanding Infantile Maxillary Sinus Osteomyelitis

- Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Infantile Maxillary Osteomyelitis

- Diagnosis of Infantile Maxillary Osteomyelitis

- Treatment of Infantile Maxillary Sinus Osteomyelitis

- Potential Complications and Long-Term Sequelae

- Differential Diagnosis of Facial Swelling and Infection in Infants

- Prevention and When to Seek Urgent Care

- References

Understanding Infantile Maxillary Sinus Osteomyelitis

Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis is a severe and uncommon bacterial infection of the bone (osteomyelitis) involving the maxilla (upper jaw bone) and specifically affecting the developing maxillary sinus in infants and young children. This condition can lead to significant morphological damage to growing tissues due to the robust vascularization of the infant's dental system and the active developmental processes occurring within the alveolar process (the part of the maxilla that holds the teeth).

Pathophysiology and Vulnerability in Infants

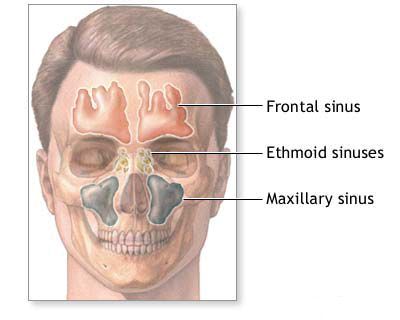

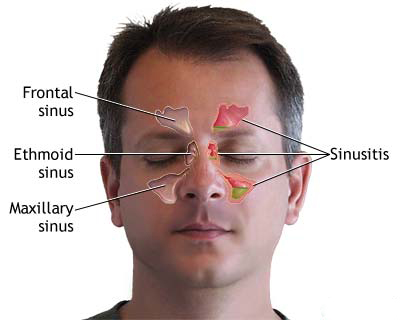

In early childhood, the maxillary sinus is relatively small and underdeveloped, and its bone is still forming and highly vascular. The developing tooth buds (germs) are embedded within the alveolar process of the maxilla, in close proximity to the sinus. This anatomical relationship makes the area susceptible to infection spreading from dental structures or adjacent tissues. The entire dental system of a child is well vascularized from birth, supporting the active growth processes related to tooth development in the alveolar process. This rich blood supply, while essential for growth, can also facilitate the spread of infection within the bone.

Acute osteomyelitis of the maxillary sinus in infants often begins as an inflammation of the alveolar process, which then spreads to involve the developing tooth germs and the body of the maxilla itself, including the rudimentary sinus cavity.

Sources and Spread of Infection

The entry points (gates) for infection leading to acute osteomyelitis of the maxillary sinus in infants can be diverse, involving adjacent organs and tissues:

- Oral Cavity: Infections around erupting teeth, trauma to the gums, or complications from dental procedures (though rare at this age).

- Nasal Cavity: Severe rhinitis or sinusitis can potentially lead to contiguous spread of infection to the maxillary bone, especially if there is mucosal breakdown or trauma.

- Conjunctiva of the Eye: Infections of the eye or lacrimal system can theoretically spread to the maxilla via anatomical connections, though this is less common.

- Hematogenous Spread: Bacteria can reach the maxillary bone via the bloodstream from a distant site of infection, although this is a less frequent cause than direct extension.

- Trauma: Direct trauma to the midface can introduce bacteria into the bone or create conditions favorable for infection.

Once established, the infection causes inflammation, bone destruction, and pus formation within the maxilla. The proximity to developing teeth means these structures are often directly involved and can be damaged or lost.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Infantile Maxillary Osteomyelitis

Acute osteomyelitis of the maxillary sinus in infants and young children presents with a constellation of local and systemic symptoms, often severe:

- Facial Swelling: Pronounced inflammatory edema (swelling) of the cheek, lower eyelid, and sometimes the side of the nose on the affected side. The swelling can be extensive and distort facial features.

- Nasal Congestion: Significant blockage of the nasal passage on the affected side.

- Purulent Nasal Discharge: Abundant, thick, pus-like discharge from the nostril on the affected side.

- Fever and Systemic Illness: High fever, irritability, lethargy, poor feeding, and signs of sepsis may be present.

- Orbital Symptoms: Swelling and redness of the eyelids (periorbital cellulitis), proptosis (bulging of the eye), and restricted eye movements can occur if the infection spreads towards the orbit.

- Oral Symptoms: Swelling and redness of the gums in the upper jaw, pain, and sometimes loosening or premature eruption/loss of developing teeth.

- Fistula Formation: As the infection progresses and bone necrosis (sequestration) occurs, a fistulous tract (an abnormal passage) may form, draining pus into the oral cavity (onto the gums or palate), nasal cavity, or externally onto the skin of the cheek or near the eye (orbit).

- Sequestrum Rejection: In severe cases, there can be spontaneous or surgical rejection of sequestra (pieces of dead bone), sometimes containing developing tooth germs. This can lead to significant defects and long-term dental and facial developmental problems.

- Pain and Tenderness: The affected area of the face and maxilla is usually very tender to palpation.

The clinical picture can evolve rapidly, and early diagnosis and aggressive treatment are crucial to prevent devastating complications.

Diagnosis of Infantile Maxillary Osteomyelitis

Diagnosing infantile maxillary osteomyelitis requires a high index of suspicion, especially in an infant presenting with facial swelling, fever, and purulent nasal or oral discharge. Diagnostic steps include:

- Clinical Examination: Careful assessment of facial swelling, orbital signs, nasal passages (for discharge and mucosal appearance), and oral cavity (for gum swelling, fistulae, or loose teeth).

- Laboratory Tests:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Typically shows leukocytosis (elevated white blood cell count) with a left shift (increased immature neutrophils).

- Inflammatory Markers: Elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

- Blood Cultures: To identify bacteremia, especially if systemic sepsis is suspected.

- Imaging Studies:

- Plain X-rays: May show soft tissue swelling and, in later stages, signs of bone destruction or sequestra, but are often not very specific in early disease.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: CT is the imaging modality of choice for evaluating osteomyelitis. It can demonstrate bone erosion, periosteal reaction (new bone formation), sequestra, and any associated soft tissue abscesses or sinus opacification. Contrast-enhanced CT can help delineate abscess collections.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is excellent for assessing soft tissue involvement, early bone marrow changes (edema), and potential intracranial or orbital complications. It is often complementary to CT.

- Ultrasound: May be useful for detecting subperiosteal fluid collections or abscesses, particularly in superficial areas.

- Needle Aspiration or Biopsy: If an abscess or fluid collection is identified, needle aspiration under imaging guidance can provide pus for Gram stain, culture (aerobic and anaerobic), and antibiotic sensitivity testing. Bone biopsy may be necessary in some cases for definitive diagnosis and microbiological confirmation, especially if imaging is inconclusive or initial treatment fails.

- Dental Evaluation: Consultation with a pediatric dentist or oral surgeon may be helpful to assess the involvement of developing teeth.

Treatment of Infantile Maxillary Sinus Osteomyelitis

The treatment of acute osteomyelitis of the maxillary sinus in infants is a medical and surgical emergency requiring prompt and aggressive management, typically involving hospitalization.

Medical Management

- Intravenous Antibiotics: High-dose, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are initiated immediately after obtaining cultures. The initial choice often covers common pathogens like *Staphylococcus aureus* (including MRSA if prevalent locally), Streptococci, and anaerobes. Antibiotic therapy is then tailored based on culture and sensitivity results. Prolonged courses of antibiotics (often 4-6 weeks or longer, sometimes with a switch to oral therapy once clinically stable) are usually necessary.

- Supportive Care: Including hydration, nutritional support, and analgesia for pain relief.

Surgical Intervention

Surgical intervention is almost always required for maxillary osteomyelitis in infants. The goals of surgery are to:

- Drain Abscesses: Incision and drainage of any localized pus collections (e.g., subperiosteal abscess, soft tissue abscess).

- Debridement of Non-viable Tissue: Removal of all infected and necrotic (dead) bone (sequestra) and soft tissue. It is crucial during surgery to be as conservative as possible and spare developing tooth germs to avoid further significant deformation of the oral cavity and impairment of future dental development. However, all non-viable tissue must be removed to control the infection.

- Obtain Cultures: Surgical specimens provide the best material for microbiological diagnosis.

- Ensure Adequate Drainage: Establishing pathways for ongoing drainage from infected areas. This might involve opening all pockets and recesses of infection.

- Sinus Drainage: If the maxillary sinus itself is involved (empyema), procedures to ensure its drainage may be necessary, though extensive sinus surgery is usually avoided in very young infants unless absolutely essential.

The surgical approach depends on the extent of the infection and may involve intraoral incisions, external incisions (used cautiously to minimize facial scarring), or combined approaches.

Supportive Therapies

Treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics is often supplemented with stimulating and supportive therapies to promote healing and recovery, such as:

- Vitamins: Ensuring adequate vitamin intake.

- Wound Care: Regular cleaning and dressing of any surgical wounds or fistulous tracts.

- Nutritional Support: Maintaining good nutrition is vital for recovery.

- Historically, agents like Aloe or Actovegin (a deproteinized hemodialysate of calf blood) were sometimes used with the aim of promoting tissue regeneration, but their efficacy is not well-established by modern evidence-based standards for this condition.

Long-term follow-up with ENT, pediatric infectious disease specialists, and pediatric dentists/oral surgeons is essential to monitor for recurrence, manage complications, and address any developmental issues related to facial growth or dentition.

Potential Complications and Long-Term Sequelae

Infantile maxillary osteomyelitis can lead to severe and lasting complications if not managed appropriately:

- Damage to Developing Teeth: Loss of tooth germs leading to missing permanent teeth.

- Facial Deformity: Due to bone destruction and impaired facial growth on the affected side.

- Chronic Osteomyelitis: Persistent or recurrent bone infection.

- Chronic Draining Fistulae: Persistent tracts draining pus to the skin or into the oral/nasal cavity.

- Orbital Complications: Spread of infection to the orbit can cause orbital cellulitis, abscess, vision loss, or even cavernous sinus thrombosis.

- Intracranial Complications: Rarely, infection can spread to cause meningitis, epidural abscess, or brain abscess.

- Sepsis and Systemic Illness: Overwhelming infection can lead to life-threatening sepsis.

- Pathological Fractures: Weakening of the maxillary bone can predispose to fractures.

- Growth Disturbances: Asymmetry of facial growth.

Differential Diagnosis of Facial Swelling and Infection in Infants

When an infant presents with acute facial swelling, fever, and signs of infection, several conditions need to be differentiated from maxillary osteomyelitis:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Infantile Maxillary Osteomyelitis | Severe facial/cheek swelling, often with orbital involvement; purulent nasal/oral discharge; fever, systemic illness; dental involvement (loose teeth, gum swelling); bone tenderness; CT/MRI shows bone destruction, sequestra, periosteal reaction. |

| Acute Maxillary Sinusitis (Empyema) | Facial pain/pressure, purulent nasal discharge, fever, congestion. Osteomyelitis is a complication. Imaging shows sinus opacification, but bone destruction is absent in uncomplicated sinusitis. |

| Dental Abscess (Odontogenic Abscess) | Localized swelling around an infected tooth, gumboil, tooth tenderness. May spread to cause facial cellulitis. Can be a precursor to osteomyelitis. |

| Orbital or Preseptal Cellulitis | Eyelid swelling, redness, warmth. Orbital cellulitis involves proptosis, restricted/painful eye movements, potential vision changes. May be secondary to sinusitis or osteomyelitis. |

| Acute Dacryocystitis (Infection of Lacrimal Sac) | Swelling, redness, tenderness at the medial canthus (inner corner of eye); tearing; pus may be expressed from puncta. |

| Facial Cellulitis (from other sources) | Spreading skin infection with redness, warmth, swelling, pain. Entry point (e.g., insect bite, skin break) may be visible. Less likely to have deep bone involvement initially. |

| Mumps (Parotitis) | Swelling of parotid gland(s), often bilateral, causing preauricular and angle-of-jaw swelling. Fever, malaise. Viral prodrome. |

| Malignant Tumors (e.g., Rhabdomyosarcoma) | Rare in infants; can present with rapidly growing facial mass. Often firm, may cause bone erosion. Requires biopsy. |

Prevention and When to Seek Urgent Care

Prevention focuses on:

- Good oral hygiene, even in infants (wiping gums).

- Prompt treatment of dental infections if they occur.

- Management of severe or recurrent sinus infections.

- Careful attention to any facial trauma.

Parents should seek **urgent medical attention** if an infant or young child develops:

- Rapidly progressing facial or cheek swelling.

- High fever with facial swelling.

- Swelling around the eye, especially if associated with bulging of the eye, difficulty moving the eye, or vision changes.

- Purulent discharge from the nose or mouth associated with facial swelling.

- Severe irritability, lethargy, or refusal to feed in the context of these symptoms.

Infantile maxillary osteomyelitis is a serious condition requiring immediate evaluation and aggressive multidisciplinary treatment to optimize outcomes and minimize long-term sequelae.

References

- Brook I. Osteomyelitis of the maxillary sinus in children. J Otolaryngol. 1995 Jun;24(3):197-200.

- Wald ER. Sinusitis in children. N Engl J Med. 1992 May 28;326(22):1493-9. (General context, osteomyelitis as a complication)

- Gellin ME. Osteomyelitis of the maxilla in infancy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1970 Feb;29(2):167-73.

- Obisesan AA, Lagundoye SB, Daramola JO, Ajagbe HA, Haddock DR. Osteomyelitis of the mandible: a review of 77 cases. Br J Oral Surg. 1977 Nov;15(2):163-9. (Context for jaw osteomyelitis)

- Jones N, Walker J. Osteomyelitis of the maxilla in infants. J Laryngol Otol. 1990 Nov;104(11):895-7.

- Berlucchi M, Nicolai P, Sabin A, et al. Maxillary osteomyelitis in children. Am J Rhinol. 2003 Nov-Dec;17(6):355-9.

- Stokroos RJ, de Koos JTH, Manni JJ. Maxillary osteomyelitis in infancy. A report of three cases. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1997 May 1;39(2):151-7.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis