Nasal polyps

Understanding Nasal Polyps

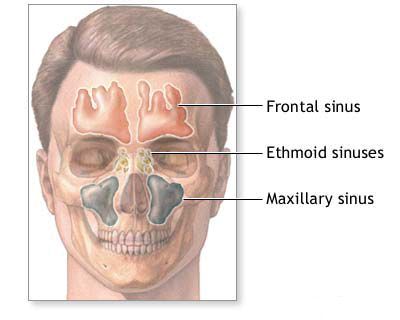

Nasal polyps are benign, teardrop-shaped, edematous (swollen) growths that originate from the mucous membrane lining the nasal cavity or paranasal sinuses, most commonly the ethmoid sinuses. They can occur in individuals of any age, including young children, and are often associated with chronic inflammatory conditions.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

The exact cause of nasal polyps is not fully understood, but they are widely believed to be the result of chronic inflammation of the sinonasal mucosa. Key associated conditions and contributing factors include:

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis (CRS): Nasal polyps are a hallmark of a specific phenotype of CRS, known as Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps (CRSwNP). This is particularly common in cases of chronic ethmoiditis. Nasal polyps have been observed even in very young children, such as a documented case in a 4-month-old infant with ethmoiditis.

- Allergy: While not all patients with polyps have allergies, there is a strong association. It is believed that polyps represent a kind of hyperplastic reaction of the nasal and sinus mucosa in response to allergens or other inflammatory triggers.

- Asthma: Particularly non-allergic (intrinsic) asthma. The triad of nasal polyps, asthma, and aspirin sensitivity (aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease - AERD, also known as Samter's triad) is a well-recognized syndrome.

- Cystic Fibrosis: Nasal polyps are common in children and young adults with cystic fibrosis.

- Allergic Fungal Rhinosinusitis (AFRS): An allergic reaction to fungi colonizing the sinuses, often leading to extensive polyposis and thick, eosinophilic mucin.

- Genetic Predisposition: Some individuals may have a genetic tendency to develop polyps.

- Chronic Irritation and Infection.

Appearance and Impact

Nasal polyps are typically grayish or yellowish-pink in color, smooth, and glistening, though their appearance can vary. They are usually insensitive to touch. Sometimes, particularly if they are large and subject to trauma or irritation, nasal polyps can become more firm, erythematous, and may bleed when touched.

The presence of polyps can significantly impair the physiological functions of the nose, leading to:

- Nasal Obstruction: Difficulty breathing through the nose, often the primary complaint.

- Hyposmia or Anosmia: Reduced or complete loss of the sense of smell, as polyps can block airflow to the olfactory region.

- Rhinorrhea: Persistent runny nose, which may be watery, mucoid, or mucopurulent if secondary infection is present.

- Post-Nasal Drip.

- Headache or Facial Pain/Pressure: Due to sinus blockage or the mass effect of large polyps.

- Hyponasal Speech (Rhinolalia Clausa): A "stuffy" or denasal voice quality.

- Deformation of the External Nose: In long-standing, extensive polyposis, particularly in children or with certain syndromes (e.g., Woakes' syndrome), the nasal bridge can widen, leading to a "frog-face" appearance.

- Secondary Infections: Impaired drainage due to polyps can lead to recurrent or chronic sinusitis, otitis media, pharyngitis, laryngitis, tracheitis, bronchitis, or exacerbate asthma.

Choanal polyps are a specific type of polyp, usually solitary, that originates within a sinus (most commonly the maxillary sinus – an antrochoanal polyp) and extends on a stalk through the sinus ostium into the nasal cavity and then posteriorly into the nasopharynx. These can cause significant nasopharyngeal obstruction and may resemble benign or even malignant nasopharyngeal tumors, necessitating careful diagnosis.

Diagnosis of Nasal Polyps

Diagnosing nasal polyps involves a combination of history, physical examination, and often imaging:

- Clinical History: Focus on symptoms like nasal obstruction, loss of smell, rhinorrhea, facial pressure, history of allergies, asthma, aspirin sensitivity, cystic fibrosis, and previous treatments.

- Anterior Rhinoscopy: Small anterior polyps may be visible.

- Nasal Endoscopy: This is the gold standard for visualizing polyps, assessing their extent, origin (e.g., middle meatus, sphenoethmoidal recess), and the overall condition of the nasal mucosa. Polyps typically appear as smooth, pale, grape-like masses.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: A CT scan of the paranasal sinuses is essential for evaluating the extent of polyposis within the sinuses, identifying associated sinus opacification, bony changes, and planning surgical treatment.

- Allergy Testing: May be performed to identify allergic triggers if suspected.

- Biopsy: While most nasal polyps have a characteristic appearance, a biopsy is crucial if a polyp is unilateral, has an unusual appearance (e.g., bloody, friable, necrotic), or if malignancy is suspected, to rule out conditions like inverted papilloma or cancer.

Treatment Strategies for Nasal Polyps

The management of nasal polyps aims to reduce their size or eliminate them, improve symptoms (especially nasal breathing and sense of smell), and reduce recurrence rates. Treatment typically involves a combination of medical and, if necessary, surgical approaches.

Medical Management

- Intranasal Corticosteroids: Sprays or drops are often the first-line treatment. They can help shrink small polyps, reduce inflammation, and alleviate symptoms. Long-term use is often required.

- Oral Corticosteroids: Short courses of systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) can significantly shrink or eliminate polyps and provide rapid symptom relief. However, due to side effects, they are not suitable for long-term continuous use but can be used for acute exacerbations or preoperatively.

- Treatment of Underlying Conditions:

- Managing allergic rhinitis with antihistamines, intranasal corticosteroids, or allergen immunotherapy.

- Optimizing asthma control.

- Treating chronic sinus infections with antibiotics if a bacterial component is evident.

- Biologic Therapies: For severe CRSwNP unresponsive to corticosteroids and surgery, newer biologic agents targeting specific inflammatory pathways (e.g., dupilumab, omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab) have shown significant efficacy in reducing polyp size, improving symptoms, and reducing the need for surgery or oral steroids.

- Aspirin Desensitization: For patients with AERD (Samter's triad), aspirin desensitization followed by daily aspirin therapy can help control polyp recurrence and respiratory symptoms.

- Nasal Saline Irrigation: Helps to clear mucus, allergens, and irritants, and can improve the efficacy of topical medications.

Surgical Management: Polypotomy, Cryopolypotomy, and Endoscopic Surgery

If medical treatment is insufficient, or if polyps are large and causing significant obstruction, surgical removal is indicated.

- Polypotomy (Simple Polyp Removal): Historically, polyps were removed using a nasal snare or forceps, often as an office procedure. This can provide temporary relief but has a high recurrence rate as it doesn't address the underlying sinus inflammation or polyp origin within the sinuses. Even the most radical surgical interventions do not always prevent the recurrence of nasal polyps. Conventional surgical interventions (especially older, more radical types) for nasal polyps can sometimes lead to atrophic changes in the nasal mucosa with subsequent crust formation, which can negatively affect nasal breathing and other physiological functions. Therefore, in children with nasal polyps, it is often better to opt for more conservative surgical intervention, such as simple removal of polyps, and only in more stubborn or extensive cases combine it with the opening of the ethmoid sinus cells.

- Cryopolypotomy (Cryosurgery for Polyps): This technique involves freezing the polyps using a cryoprobe. It may be considered a potentially preferable treatment. Often, the bulk of the polyps is removed by conventional means first, and then cryotherapy is used for more thorough removal of remnants or smaller lesions. Small polyps can be frozen under the control of an operating microscope using a thin cryoprobe. If the olfactory cleft is cleared during cryotherapy, the sense of smell may improve. Removal of polyps from the area of the natural ostia of the paranasal sinuses can often restore sinus function. Anesthesia for cryopolypotomy can sometimes be achieved with weaker anesthetics than for conventional surgery (e.g., 0.5-1% dicaine solution or 3-5% cocaine solution with 0.1% adrenaline). The entire half of the nasal cavity is anesthetized. The cryoprobe, cooled in a Dewar vessel (thermos), is applied to the polyp and immediately freezes to it. Traction is applied, and the polyp is removed. The cryoprobe with the attached polyp is then immersed in hot water to quickly detach the polyp. Smaller polyps can be removed by successive applications. If a polyp has a very thick stalk but is large, slight rotation can aid extraction. The cryoprobe is placed between the branches of a nasal dilator to protect surrounding mucosa. Nasal tamponade may sometimes be avoided, which is beneficial for children. Typically, 9-12 cryotherapy sessions (this likely refers to multiple applications or treatment of multiple polyps in sessions, not 9-12 separate surgical dates) might be performed.

Considerations for Specific Syndromes

In patients diagnosed with specific syndromes associated with polyposis, more persistent and often repeated treatment is required:

- Kartagener's Syndrome: A triad of situs inversus (opposite arrangement of internal organs), chronic sinusitis/nasal polyposis, and bronchiectasis. Due to underlying ciliary dysfunction, recurrent infections and polyp regrowth are common.

- Woakes' Syndrome (Juvenile Recurrent Nasal Polyposis): Characterized by early-onset, aggressive, recurrent nasal polyposis, often accompanied by deformation of the external nose (broadening of the nasal bridge) and sometimes intestinal involvement (though this association is less consistently defined in modern literature).

Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (FESS) and Ethmoidectomy

Principles of Endoscopic Intervention

Modern surgical management of nasal polyps, especially when associated with chronic rhinosinusitis, primarily involves **Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (FESS)**. This technique can be performed at any age, including in children when indicated.

The goals of FESS for nasal polyps include:

- Complete removal of polyps from the nasal cavity and involved sinuses.

- Opening and widening the natural drainage pathways of the paranasal sinuses.

- Removing diseased mucosa while preserving healthy tissue.

- Improving ventilation of the sinuses.

- Facilitating the delivery of topical medications (e.g., corticosteroid sprays, rinses) to the sinus cavities postoperatively, which is crucial for preventing recurrence.

If, after conventional polypotomy or cryopolypotomy, nasal breathing improves but hyposmia or anosmia persists, the cause may be small residual polyps or remnants deep within the nasal cavity, particularly in the olfactory cleft, which may not have been visible without magnification. If the aim of surgery is to improve both nasal breathing and the sense of smell, a two-stage approach might be used: first, removal of the bulk of polyps without surgical optics, and then meticulous removal of their remnants under the control of an operating microscope or endoscope. It is generally better to remove small polyps under microscopic or endoscopic control to maintain the integrity of unchanged mucous membrane. Polyps originating from the superior-posterior part of the nasal cavity, near the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone (where olfactory nerves pass), must be removed with extreme care and caution (without excessive traction) under direct vision with surgical optics to avoid intracranial injury.

Before an endonasal opening of the ethmoid sinus (ethmoidectomy), the child's nasal cavity is carefully examined. If it is wide, the middle turbinate can serve as a landmark. In a narrow nasal cavity, it may be advisable to first create wider access to the ethmoid sinus (e.g., by submucosal resection of a deviated nasal septum or careful lateralization/reduction of the inferior turbinate). The middle turbinate can be gently displaced medially towards the septum using the blades of a Killian's nasal speculum, allowing access to open the underlying ethmoid cells. The anterior, middle, and then posterior groups of ethmoid air cells are opened sequentially, potentially up to the sphenoid sinus, creating a common cavity or marsupializing the cells. To open the ethmoid sinus, the middle turbinate is sometimes partially or fully resected at its base, and some ethmoid cells are removed, forming a wide communication between the sinus system and the nasal cavity. External methods of opening the ethmoid sinus are rarely used in children today.

In adolescents and adults, nasal polyps are understood as pathological changes where normal-appearing mucous tissue hypertrophies, forming edematous, often translucent structures with a thin connective tissue stroma and abundant eosinophilic infiltrate. Typically, polyps have a slender pedicle (stalk) extending from the lateral surface of the middle turbinate or surrounding ethmoidal regions. They commonly protrude from the middle meatus – the area where the drainage ostia of the maxillary, frontal, and anterior ethmoid sinuses are located.

Microscopic Surgery of the Ethmoid Sinus

Microsurgery of the ethmoid sinus is performed after topical anesthesia and vasoconstriction of the middle turbinate and middle nasal passage (e.g., with 0.1% adrenaline solution, 2% pyromecaine solution) and mucosal infiltration with local anesthetic (e.g., 0.5% novocaine solution). For patients prone to psychomotor agitation, combined anesthesia (e.g., neuroleptanalgesia with droperidol and fentanyl combined with local anesthesia) may be advisable.

The cells of the ethmoid sinus are opened with specialized microinstruments under the direct vision of an operating microscope or endoscope. This technique allows for the most gentle intervention possible, helps avoid complications, and can improve the drainage and health of the remaining sinuses. Under surgical optics, only pathologically altered tissues are removed. Various magnifications are used during the operation to assess the condition of the mucosal lining of the sinus cells. Both limited ethmoidotomy (opening cells) and more extensive ethmoidectomy (removing cell partitions) are best performed using surgical optics, as ethmoid cells, especially in the posterior region, can be difficult to distinguish and may not be completely addressed when viewed with the naked eye.

In the postoperative period, the mucous membrane of the opened sinus cells is managed with continued anemization (decongestion as needed), nasal saline irrigations, topical corticosteroids, and sometimes systemic drug therapy (e.g., short course of oral steroids or antibiotics if indicated). Physiotherapy may also be part of postoperative care in some protocols.

Recurrence of Nasal Polyps

Nasal polyps frequently recur, with rates varying depending on the underlying cause, extent of disease, and thoroughness of treatment. Recurrence can happen anywhere from several months to many years after initial removal. Factors contributing to recurrence include:

- Insufficient or Incomplete Removal of Polyps: Microscopic or residual polypoid tissue left behind.

- Persistent Underlying Inflammation: If the chronic inflammatory process (e.g., in CRSwNP, allergy, AFRS) is not adequately controlled medically post-surgery. This may involve deep inflammation reaching the bone marrow.

- Undetected or Unresolved Inflammatory Condition of the Paranasal Sinuses: Ongoing sinusitis provides a stimulus for polyp regrowth.

- Generalized Polypous Degeneration of the Mucous Membrane: A widespread tendency of the sinonasal lining to form polyps.

Long-term medical management, often with intranasal corticosteroids and regular follow-up, is crucial to minimize recurrence.

Differentiating Nasal Polyps from Other Nasal Conditions

It is important to differentiate nasal polyps from other conditions that can cause nasal obstruction and similar symptoms. Besides polyps, difficulty in nasal breathing can be caused by a deviated nasal septum, diffuse or limited hypertrophy of the nasal turbinate mucosa, or enlarged adenoids (pharyngeal tonsil). This list could be extended to include tumors, foreign bodies, etc. Histological examination of removed tissue confirms the diagnosis of polyps.

The treatment approach differs: nasal polyps are primarily removed surgically (though medical therapy is key for management and recurrence prevention), while diffuse mucosal thickening (e.g., in hypertrophic rhinitis) may respond to local drug treatment or less extensive surgical reduction. Polyp removal often requires multiple sessions if extensive or recurrent, whereas hypertrophic turbinates might be addressed in a single procedure. Nasal tamponade is often avoided after simple polypectomy, but after turbinate reduction, packing may be used for 1-2 days (though some surgeons avoid routine packing to reduce risk if the patient is under constant supervision). Relapse after properly performed surgery for hypertrophic nasal mucosa is less common than polyp recurrence.

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Nasal Polyps | Pale, grayish, grape-like, often bilateral (except antrochoanal), mobile masses from middle meatus or ethmoids. Associated with CRSwNP, allergy, asthma, CF. Often cause anosmia. |

| Hypertrophied Turbinates | Enlarged, pink/red (sometimes pale/boggy in allergy) inferior or middle turbinates. Bony core may be enlarged. May shrink with decongestants (if primarily vascular). |

| Deviated Nasal Septum | Midline cartilage/bone is bent to one side, causing fixed obstruction. Visible on rhinoscopy. |

| Adenoid Hypertrophy (in children) | Causes nasopharyngeal obstruction, mouth breathing, snoring, hyponasal speech. Diagnosed by endoscopy or lateral neck X-ray. |

| Sinonasal Tumors (Benign/Malignant) | Often unilateral, may cause pain, bleeding, facial swelling, or cranial nerve symptoms. Appearance can vary, sometimes mimicking polyps. Biopsy is essential. |

| Nasal Foreign Body | Usually unilateral, foul purulent discharge, history of insertion (often in children). |

When to Consult an ENT Specialist

Consultation with an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist is recommended if:

- Persistent nasal obstruction or congestion is experienced.

- There is a significant reduction or loss of the sense of smell.

- Chronic or recurrent nasal discharge or post-nasal drip occurs.

- Facial pain or pressure suggestive of sinusitis is persistent.

- Nasal polyps are suspected or have been previously diagnosed and symptoms recur.

- Unilateral nasal symptoms (obstruction, bleeding, discharge) are present, as this can be a sign of a more serious condition.

An ENT specialist can perform a thorough evaluation, including nasal endoscopy and imaging if necessary, to accurately diagnose the presence and extent of nasal polyps and associated sinonasal disease, and to develop an appropriate medical and/or surgical management plan.

References

- Fokkens WJ, Lund VJ, Hopkins C, et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020 (EPOS 2020). Rhinology. 2020 Feb 20;58(Suppl S29):1-464.

- Stevens WW, Schleimer RP, Kern RC. Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2016 Jul-Aug;4(4):565-72.

- Bachert C, Gevaert P, van Cauwenberge P. Nasal polyps: a new concept on the topical steroid treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2002 Aug;3(8):1097-107.

- Lund VJ, Kennedy DW. Staging for rhinosinusitis. Rhinology. 1995;33(4):183-4. (Historical context for staging, often involving polyps)

- Stammberger H. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery. The Messerklinger technique. Philadelphia: BC Decker; 1991. (Seminal work on FESS, often for polyps)

- Hopkins C. Chronic Rhinosinusitis with Nasal Polyps. N Engl J Med. 2019 Jul 4;381(1):55-63.

- Newton JR, Ah-See KW. A review of nasal polyposis. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008 Apr;4(2):507-12.

- Mygind N, Dahl R, Bachert C. Nasal polyposis, eosinophilic sinusitis, and ASA intolerance. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2000 Jul-Aug;21(4):237-41.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis