Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Understanding Nasal Foreign Bodies (NFBs)

- Rhinoliths (Nasal Stones or Calculi)

- Live Nasal Foreign Bodies (Nasal Myiasis and Helminths)

- General Symptoms of Nasal Foreign Bodies

- Diagnosis of Nasal Foreign Bodies

- Treatment and Removal of Nasal Foreign Bodies

- Differential Diagnosis of Unilateral Nasal Symptoms

- Prevention of Nasal Foreign Bodies

- When to Seek Medical Attention

- References

Understanding Nasal Foreign Bodies (NFBs)

Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs) are objects lodged within the nasal cavity that are not naturally found there. This is a common issue encountered by physicians, particularly otolaryngologists and pediatricians. Despite its frequency, comprehensive summarized data on NFBs can be limited in medical literature, often with only case reports described, sometimes without specific emphasis on potential diagnostic or management errors. NFBs occur predominantly in young children, typically between the ages of 1 and 8 years, who may insert objects into their noses out of curiosity. Consequently, diagnostic and removal challenges are more common in pediatric otorhinolaryngology.

Prevalence and Common Locations

Foreign bodies often lodge in the right nasal cavity more frequently than the left, possibly due to right-handedness in most children. The object is most commonly found in the anterior part of the inferior nasal passage, just under the inferior turbinate, or less commonly in the middle meatus. Superior nasal passage involvement is rare. Occasionally, NFBs can be iatrogenic, meaning they are inadvertently left behind after medical or surgical procedures (e.g., pieces of cotton wool, gauze swabs, fragments of surgical instruments).

Modes of Entry and Types of NFBs

Foreign bodies can enter the nasal cavity in several ways:

- Self-Introduced: The most common scenario, especially in children, where the individual inserts the object themselves.

- Introduced by Another Person: Often during play among children, or rarely, during medical manipulations if care is not taken.

- Accidental Entry:

- Through the anterior nares (nostrils) by accident.

- Through the posterior nasal apertures (choanae) during vomiting, particularly if there is soft palate paralysis or congenital palatal anomalies that impair the normal closure of the nasopharynx during emesis.

- Traumatic Implantation: Foreign bodies can become embedded in the nasal cavity during facial trauma if the integrity of the nasal walls is breached. However, even in children, this is a relatively rare mode of entry.

NFBs can be a wide variety of items, including organic matter (e.g., food particles like peas or nuts, fruit seeds, pieces of paper or cotton) and inorganic matter (e.g., coins, beads, small plastic or metal parts from toys, button batteries, pencil lead). It's important to note that, rarely, what appears to be a foreign body could be an ectopic tooth (e.g., incisors or canines) that has grown into the nasal cavity due to an inversion of the tooth germ (heterotopia).

Potential Consequences of Retained NFBs

The presence of an NFB, typically a unilateral process, can lead to several local complications:

- Nasal Obstruction: Difficulty breathing through the affected nostril.

- Purulent Rhinorrhea: A foul-smelling, often unilateral, purulent (pus-like) nasal discharge is a hallmark sign, especially with long-standing NFBs.

- Epistaxis (Nosebleed): Sharp or irritating foreign bodies can damage the delicate nasal mucosa, causing bleeding.

- Olfactory Disturbance: If an NFB is lodged in the middle nasal meatus or higher, it can impair the sense of smell (hyposmia or anosmia).

- Epiphora (Watery Eyes): Blockage of the nasolacrimal duct opening in the inferior meatus can cause excessive tearing.

- Sinusitis: Prolonged retention of an NFB can lead to inflammation and infection of the paranasal sinuses due to obstruction of their drainage pathways.

- Granulation Tissue Formation: The body may react to a chronic NFB by forming granulation tissue around it, which can obscure the object and bleed easily.

- Rhinolith Formation: Over time, mineral salts from nasal secretions can deposit on a retained NFB, forming a nasal stone or rhinolith (see section #2).

- Pressure Necrosis and Perforation: Long-term pressure from an NFB can cause necrosis of the septal cartilage or lateral nasal wall, potentially leading to septal perforation or other structural damage.

- Osteomyelitis: Prolonged pressure on underlying bone can rarely lead to bone infection.

In young children, a persistent unilateral foul-smelling, purulent nasal discharge is a highly reliable sign indicative of an NFB. Diagnosis can sometimes be challenging if significant granulation tissue develops around the foreign body, masking its presence. Careful probing with a blunt metal instrument can help identify hard foreign bodies by eliciting a characteristic "gritty" sensation or metallic click, thus avoiding diagnostic errors. Contrast-enhancing foreign bodies (e.g., metallic objects) can be detected by radiography or computed tomography (CT). If exuberant granulation tissue is present, it is crucial to differentiate this from a malignant tumor of the nasal cavity, especially in older individuals, which may require a biopsy.

Rhinoliths (Nasal Stones or Calculi)

Formation and Characteristics

Rhinoliths, also known as nasal stones or calculi, are concretions that form within the nasal cavity. While some authors consider them a type of long-standing foreign body, they are essentially formed by the progressive deposition of mineral salts (primarily calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate, and magnesium phosphate) from nasal mucous secretions and lacrimal fluid around a central nidus. This nidus is often a small, initially overlooked exogenous (external) foreign body (e.g., a bead, seed, paper wad) or, less commonly, an endogenous (internal) nidus such as a blood clot, desquamated epithelial cells, or inspissated mucus.

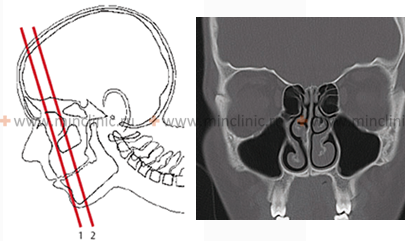

The formation of rhinoliths is facilitated by chronic inflammation and changes in the nasal cavity environment that cause stagnation of mucous secretions. Factors like a deviated nasal septum or hypertrophy of turbinates, which impair normal nasal airflow and drainage, can contribute to their development. Rhinoliths can vary greatly in shape (oval, round, flat, irregular) and size, sometimes growing to form a cast of the nasal cavity. They are often single but can occasionally be multiple, so a thorough inspection of the entire nasal cavity up to the choanae is necessary to avoid missing additional stones.

Symptoms and Treatment of Rhinoliths

The leading symptoms of a rhinolith are similar to those of other long-standing NFBs:

- Unilateral nasal obstruction.

- Foul-smelling, purulent (pus-like) or mucopurulent nasal discharge from the affected side.

- Epistaxis (nosebleeds).

- Facial pain or headache on the affected side.

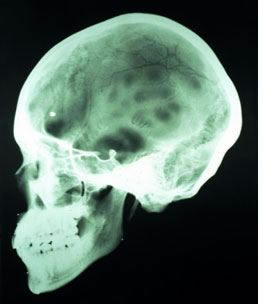

Granulation tissue may proliferate around the rhinolith. In some cases, patients may experience more general symptoms like headache or poor sleep. The differential diagnosis should include simple osteomas (benign bone tumors) and other types of foreign bodies. Rhinoliths typically appear as radiopaque masses on X-rays or CT scans.

Treatment for rhinoliths consists of their removal. Smaller rhinoliths may sometimes be removed instrumentally in an outpatient setting after local anesthesia and nasal decongestion. Larger or impacted rhinoliths often require surgical removal under general anesthesia, sometimes involving fragmentation of the stone before extraction to minimize trauma to surrounding nasal structures.

Live Nasal Foreign Bodies (Nasal Myiasis and Helminths)

While less common than inanimate objects, live organisms can also become foreign bodies within the nasal cavity, leading to distinct clinical presentations.

Types of Live NFBs and Symptoms

- Helminths (Worms):

- Ascaris lumbricoides (Roundworms): Larvae can migrate to the lungs and then up the tracheobronchial tree to be swallowed. Adult worms can occasionally enter the upper respiratory tract (nasopharynx, nasal cavity) from the digestive tract during vomiting or by active crawling. Patients, often children, may complain of headache and discomfort or a crawling sensation in the nose. Movement or manipulation of Ascaris can cause them to enter the paranasal sinuses, larynx, or trachea, potentially leading to asphyxia and, in severe cases, death.

- Enterobius vermicularis (Pinworms): Can occasionally migrate from the perianal region or be transferred from the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., during vomiting) into the nasal cavity.

- Leeches (Hirudinea): Can attach to the nasal mucosa if contaminated water from stagnant ponds or streams is drunk or used for nasal irrigation. This typically results in persistent unilateral epistaxis, nasal obstruction, and an itching or crawling sensation.

- Insect Larvae (Nasal Myiasis): Maggots (larvae of certain fly species, e.g., from the families Calliphoridae, Sarcophagidae, Oestridae) can infest the nasal cavity, particularly in individuals with poor hygiene, open nasal wounds, atrophic rhinitis with crusting, or in debilitated states, especially in tropical and subtropical regions. The larvae attach to the nasal mucosa using their oral hooks or spines and can cause extensive tissue destruction, including erosion of mucosa, cartilage, periosteum, and underlying bone. This can be extremely painful and lead to severe complications. Children may complain of headache (frontal and parietal areas), dizziness, and a foul-smelling, bloody nasal discharge (a tumor must be excluded). Movement of the larvae causes intense irritation and frequent sneezing.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Live NFBs

- Ascaris and Pinworms: Diagnosis is made by visualizing the worm. Removal is done carefully with forceps. Systemic antihelminthic treatment is also required. Lubricating the nasal mucosa with menthol oil was a historical method to immobilize pinworms before removal.

- Leeches: Diagnosis by direct visualization. Leeches are extracted by grasping them firmly with forceps. Applying saline, lidocaine, or vinegar to the leech may help it detach.

- Nasal Myiasis (Maggots): Diagnosis is made by anterior rhinoscopy, which reveals moving white maggots on the nasal mucosa. Optical aids (endoscopy) are essential for thorough examination and to clarify the extent of tissue involvement. Treatment involves:

- Anemization of the nasal mucosa (e.g., with epinephrine or oxymetazoline) to improve visualization and reduce bleeding.

- Meticulous manual removal of all visible larvae using forceps, often under local or general anesthesia.

- Irrigation of the nasal cavity with saline or mild antiseptic solutions.

- Instillation of substances to immobilize or kill larvae (e.g., chloroform water, turpentine oil, or oily substances like liquid paraffin were historically used, but modern practice may involve safer larvicidal agents or systemic ivermectin in some cases). Special care is crucial during manipulation due to the risk of larvae penetrating into the orbit or brain through eroded bone.

- Systemic antibiotics are usually given to prevent secondary bacterial infection.

- Wound debridement if significant tissue necrosis has occurred.

General Symptoms of Nasal Foreign Bodies

Summarizing the typical presentations of NFBs:

- Sharp Objects: Usually cause immediate pain in the nose and often epistaxis (nosebleed).

- Objects that Swell (e.g., beans, peas, sponges): Initially may cause little discomfort, but as they absorb moisture and swell, they progressively obstruct nasal breathing and lead to inflammation with purulent discharge.

- Small, Smooth, Inert Objects: Can remain asymptomatic for a long time. They may be discovered incidentally or eventually dislodge and pass into the nasopharynx, potentially being swallowed or, more dangerously, aspirated into the larynx, trachea, or bronchi.

- Long-Retained Foreign Bodies: Become a chronic irritant, causing persistent unilateral rhinitis, foul-smelling purulent discharge, and the formation of granulation tissue around the object. Over time, mineral salts can deposit on and around the foreign body, leading to the formation of a rhinolith. The etiology of all rhinoliths is not solely due to a pre-existing foreign body; some may form around an endogenous nidus.

Diagnosis of Nasal Foreign Bodies

When an NFB is suspected, especially with symptoms like unilateral nasal congestion, purulent or bloody discharge with an unpleasant odor, the diagnostic process includes:

- Detailed Anamnesis (History): Inquire about potential insertion events (especially in children, though they may not admit it), onset and nature of symptoms.

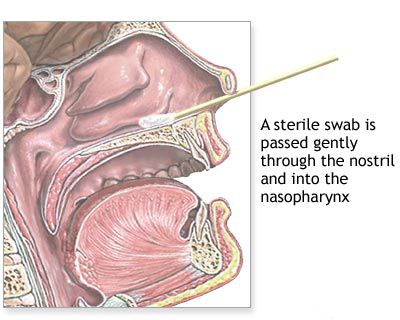

- Anterior Rhinoscopy: Direct visualization of the nasal cavity. Application of a topical decongestant (e.g., 0.1% adrenaline or oxymetazoline solution) can reduce mucosal swelling and improve visualization.

- Nasal Endoscopy: Use of a rigid or flexible endoscope is invaluable for finding small NFBs, those located posteriorly, or those obscured by swollen mucosa or granulation tissue.

- Palpation with a Probe: A blunt metal probe can be gently used to feel for a hard foreign body, especially if it's not clearly visible.

- Imaging:

- Radiography (X-rays): Useful for detecting radiopaque foreign bodies (e.g., metallic objects, some types of glass, rhinoliths, ectopic teeth). Lateral and frontal projections of the nose and facial bones are typically obtained.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: May be used in complex cases, to determine the exact location and depth of penetration of an NFB, to assess for complications like sinusitis or bony erosion, or if other imaging is inconclusive.

Treatment and Removal of Nasal Foreign Bodies

An NFB may occasionally be expelled spontaneously (e.g., during sneezing or vigorous nose blowing), but instrumental removal by a healthcare professional is usually required. The primary goal during removal is to extract the object completely and safely, preventing its aspiration into the lower respiratory tract or pushing it further into the nasal cavity or nasopharynx.

Non-Instrumental Removal Methods (Use with Caution)

- Vigorous Nose Blowing: Applicable only in older, cooperative children or adults who can effectively blow their nose while occluding the unaffected nostril.

- "Parent's Kiss" or Positive Pressure Technique: For young children, a parent or caregiver can deliver a puff of air into the child's mouth while occluding the unaffected nostril. This may dislodge the NFB. This should be attempted cautiously.

- Politzer Maneuver (Historical): Blowing air into the mouth or the unaffected nostril using a Politzer bag was a historical method but carries risks.

Instrumental Removal Methods

This is the surest way but requires skill and appropriate conditions. Pre-procedural anemization (decongestion) and topical anesthesia of the nasal mucosa are crucial for better visualization and patient comfort.

- Blunt Hook or Right-Angle Probe: Ideal for removing firm, rounded, or irregular objects. The instrument is carefully advanced past the foreign body, and then its curved end is used to engage and withdraw the object along the floor of the nasal cavity in an anterior direction.

- Nasal Forceps (Alligator, Bayonet, or Hartmann): Useful for grasping flat objects (like buttons, paper) or soft, compressible items (cotton, swollen peas, seeds). They can be used to grasp objects that can be engaged from the sides.

- Suction Catheter: Can be effective for removing small, lightweight, or spherical objects, or copious secretions obscuring an NFB.

- Balloon Catheter (e.g., Fogarty): A thin catheter with an inflatable balloon at the tip can be passed beyond the NFB, the balloon inflated, and then the catheter withdrawn, pulling the object out.

- Cyanoacrylate Adhesive (Medical Grade "Super Glue"): A drop of glue on the tip of a blunt applicator can be touched to a dry, visible foreign body; once adhered, it can be withdrawn. This requires a cooperative patient and careful application to avoid gluing nasal tissues.

Wedged or very large NFBs may need to be fragmented (crushed) carefully before piecemeal extraction. This often requires general anesthesia.

Important Considerations and Cautions During Removal

- Patient Cooperation and Immobilization: Essential, especially in children. If a child is uncooperative, removal under sedation or general anesthesia may be necessary to prevent injury or aspiration. The child must be held tightly and securely.

- Good Illumination and Visualization: A headlight and nasal speculum or endoscope are vital.

- Avoid Pushing Deeper: Attempts to remove round objects with forceps or tweezers are often unsuccessful and can push the NFB further posteriorly.

- Risk of Aspiration: Always be prepared for the possibility of the NFB dislodging into the pharynx and potentially being aspirated. Positioning the patient appropriately (e.g., head slightly tilted forward or in Trendelenburg if under general anesthesia) can help.

- Bleeding: Some bleeding is common. Adequate decongestion helps minimize it. Suction should be available.

- Multiple Attempts: If the first attempt at removal fails, or if the NFB is large, deeply impacted, or poorly visible, it is often wiser to refer to an experienced specialist or proceed with removal under general anesthesia rather than making repeated traumatic attempts. This is especially true if the child becomes distressed, as this causes pain, bleeding, and greatly complicates further efforts.

![]() Attention! Do not attempt to remove a nasal foreign body by forceful blowing of air or by pouring water into the healthy (unaffected) nasal side. Such methods can create high pressure, risking the penetration of nasal discharge or irrigation fluid into the Eustachian (auditory) tubes, potentially causing purulent otitis media, while the foreign body may remain unremoved. The principles for removing foreign bodies from the external auditory canal do not directly apply here.

Attention! Do not attempt to remove a nasal foreign body by forceful blowing of air or by pouring water into the healthy (unaffected) nasal side. Such methods can create high pressure, risking the penetration of nasal discharge or irrigation fluid into the Eustachian (auditory) tubes, potentially causing purulent otitis media, while the foreign body may remain unremoved. The principles for removing foreign bodies from the external auditory canal do not directly apply here.

Topical application of a decongestant and anesthetic solution (e.g., 10% cocaine solution was historically mentioned for its vasoconstrictive and anesthetic properties, though modern practice uses safer alternatives like oxymetazoline with lidocaine) can greatly facilitate the task by reducing mucosal swelling (especially of the anterior end of the inferior nasal concha) and weakening the child's defensive movements.

Post-Removal Care

After successful removal of an NFB, nasal patency is usually restored quickly. Any associated inflammation, swelling, or modified mucus discharge typically resolves within a few hours or days, often without requiring further specific treatment. If there is significant mucosal trauma or secondary infection, a short course of topical antibiotic ointment or saline nasal sprays may be recommended.

Differential Diagnosis of Unilateral Nasal Symptoms

Unilateral nasal obstruction, discharge (especially if foul-smelling or bloody), or pain should always raise suspicion of an NFB, particularly in children. However, other conditions can present similarly:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Nasal Foreign Body | Often history of insertion (may be unwitnessed); unilateral foul purulent discharge, epistaxis, obstruction. Object visible on examination/imaging. |

| Unilateral Sinusitis | Purulent discharge, facial pain/pressure, congestion. Often follows URI. CT confirms sinus opacification. NFB can cause secondary sinusitis. |

| Nasal Polyp (Unilateral, e.g., Antrochoanal Polyp) | Gradual onset of obstruction, mucoid discharge. Pale, grape-like mass visible on endoscopy. |

| Deviated Nasal Septum with Impaction | Congenital or traumatic; fixed obstruction. Septal deviation visible. |

| Nasal Tumor (Benign or Malignant) | Progressive unilateral obstruction, epistaxis, pain, facial swelling, cranial nerve deficits. Requires imaging and biopsy. More common in adults. |

| Choanal Atresia (Unilateral) | Congenital blockage of posterior nasal opening; persistent unilateral obstruction and discharge from birth. |

| Dental Abscess with Nasal Fistula | Foul discharge, pain related to an infected upper tooth. |

Prevention of Nasal Foreign Bodies

Prevention is key, especially for young children:

- Supervision: Closely supervise young children during play, especially with small objects, toys with small parts, or certain foods (nuts, seeds).

- Age-Appropriate Toys: Ensure toys are appropriate for the child's age and do not have small, detachable parts.

- Safe Environment: Keep small items like coins, buttons, beads, button batteries, and small hardware out of reach of young children.

- Education: Explain the danger of putting objects into the nose (and ears/mouth) to older children, parents, and caregivers.

- Medical Professional Vigilance: Healthcare providers should exercise meticulous care during nasal procedures to prevent iatrogenic NFBs (e.g., ensuring all cotton/gauze is removed). This constitutes medical malpractice if objects are left behind, potentially leading to litigation.

When to Seek Medical Attention

Immediate medical attention from an ENT specialist or emergency department is warranted if:

- A nasal foreign body is suspected or witnessed.

- There is unilateral, foul-smelling nasal discharge, especially in a child.

- There is persistent unilateral nasal obstruction or bleeding.

- Initial attempts at home removal (if appropriate and safe for the object type) are unsuccessful.

- The object is a button battery (caustic and can cause rapid tissue damage) or paired magnets (can cause pressure necrosis).

- The patient is distressed, uncooperative, or there is significant pain or bleeding.

Prompt and skilled removal minimizes the risk of complications.

References

- Figueiredo RR, Azevedo AA, Kós AOA, Tomita S. Nasal foreign bodies: description of 102 cases. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol (Engl Ed). 2006 Jan-Feb;72(1):18-23.

- Kiger JR, Brenkert TE, Losek JD. Nasal foreign body removal in children. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008 Nov;24(11):785-92.

- Lin VY, Daniel SJ, Papsin BC. Button batteries in the ear, nose and upper aerodigestive tract. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004 Apr;68(4):473-9.

- Kucik CJ, Clenney T. Management of common nasal foreign bodies. Am Fam Physician. 2005 Oct 1;72(7):1311-4.

- Barros GC, ArTaha S, Belling C, et al. Diagnosis and management of nasal foreign bodies: a literature review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2022 Nov-Dec;88(Suppl 3):S80-S89.

- Schwartz RH, Bahadori RS. Nasal foreign bodies: an update and review. Consultant for Pediatricians. 2008;7(8):337-342.

- Kadish HA, Corneli HM. Removal of nasal foreign bodies in the pediatric population. Am J Emerg Med. 1997 Jan;15(1):54-6.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis