Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis

- Introduction to Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

- Benign Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

- Malignant Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal sinuses

- Rare Nasal Tumors: Esthesioneuroblastoma and Chemodectoma

- Sarcoidosis of the Nose (Benign-Beck-Schaumann Disease)

- Surgical Approaches for Sinonasal Tumors

- Differential Diagnosis of Unilateral Nasal Mass/Obstruction

- Prognosis and When to Seek Specialist Care

- References

Introduction to Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

The nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses, due to their complex embryological development from various tissue origins, can give rise to a diverse array of tumor-like formations, benign tumors, and malignant neoplasms. These tumors often exhibit complex, sometimes combined, histological structures. The nose itself is a relatively narrow cavity, in some areas with rather thin bony walls, yet it is richly supplied with blood vessels and nerves.

Anatomical Considerations and Challenges

The intimate anatomical relationship of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses with surrounding vital structures—including the brain, orbits (eyes), and pharynx—poses significant challenges. Malignant tumors in this region have a tendency to grow and spread rapidly to these adjacent organs. This aggressive local invasion can create considerable difficulties in the diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of sinonasal tumors, often requiring multidisciplinary approaches involving ENT surgeons, oncologists, radiologists, and neurosurgeons.

Benign Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

Common Types and Characteristics

A variety of benign tumors can arise in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Common types include:

- Angiomas (Hemangiomas and Lymphangiomas): Vascular tumors. A specific type, often referred to as a "bleeding polyp of the nasal septum" (septal angioma or pyogenic granuloma), typically occurs in the anterior part of the nasal septum (Kiesselbach's plexus). It presents as a soft-elastic, red or bluish tumor, up to 6-8 mm in size, which bleeds easily upon contact. Histologically, it often resembles a fibroma with a well-developed network of blood vessels. Other angiomas can be found on the nasal septum or turbinates.

- Papillomas: These are epithelial tumors that can have various morphologies (e.g., squamous, inverted, oncocytic). Inverted papillomas, though benign, are locally aggressive and have a tendency for recurrence and, rarely, malignant transformation. They often arise from the lateral nasal wall or sinuses. Squamous papillomas are more common in the nasal vestibule.

- Fibromas: Tumors arising from fibrous connective tissue.

- Pigmented Tumors (Nevi): Moles within the nasal cavity, which are rare.

- Chondromas and Osteomas: Cartilaginous and bony tumors, respectively. These are extremely rare in children. Osteomas more commonly originate from the frontal or ethmoid sinuses and can grow into the nasal cavity or orbit.

- Other Tumor-like Formations: Such as mucoceles, pyoceles, cholesterol granulomas, and fibrous dysplasia.

Diagnosis of Benign Tumors

Symptoms of benign sinonasal tumors can vary depending on their size and location but may include:

- Unilateral nasal obstruction

- Epistaxis (nosebleeds), especially with vascular tumors like angiomas

- Facial pain or pressure

- Anosmia or hyposmia (reduced sense of smell)

- Facial deformity or swelling

- Visual disturbances (e.g., proptosis, diplopia) if the tumor extends into the orbit (common with osteomas).

Diagnosis is established through:

- Rhinoscopy and Nasal Endoscopy: For direct visualization of the tumor.

- Probing and Palpation: To assess consistency and attachment.

- Imaging: X-rays and, more definitively, Computed Tomography (CT) scans or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) help determine the tumor's origin, extent, and relationship to surrounding structures. CT is excellent for bony tumors like osteomas.

- Histological Examination (Biopsy): Essential for confirming the benign nature of the tumor and its specific type.

Treatment of Benign Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

The primary treatment for most symptomatic benign sinonasal tumors is **surgical excision**. The surgical approach depends on the tumor's size, location, and type. Endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) techniques are commonly used for complete and minimally invasive removal.

In some cases, particularly for vascular tumors (angiomas), adjunctive or alternative treatments may include:

- Electrocoagulation or Surgical Diathermy: To control bleeding and ablate tumor tissue.

- Cryotherapy: Freezing the tumor tissue.

- Beta-therapy (Radiation): Rarely used for specific benign conditions.

- Embolization: Preoperative embolization may be used for highly vascular tumors to reduce intraoperative bleeding.

Malignant Tumors of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

Types of Malignant Tumors

Malignant tumors of the sinonasal tract can be broadly classified into connective tissue origin (sarcomas) and epithelial origin (carcinomas).

- Sarcomas: These are less common than carcinomas. Various types can occur:

- Round-cell sarcoma

- Spindle-cell sarcoma

- Giant cell sarcoma

- Fibrosarcoma

- Osteosarcoma (bone)

- Chondrosarcoma (cartilage)

- Reticulosarcoma

- Lymphosarcoma (a type of lymphoma)

- Carcinomas: These are epithelial tumors and are more common overall in adults. Types include:

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma: The most common type of sinonasal cancer.

- Basal cell carcinoma (typically of the external nose skin)

- Cylindrical cell carcinoma

- Adenocarcinoma (glandular origin)

- Adenoid cystic carcinoma

- Mucoepidermoid carcinoma

- Undifferentiated carcinoma

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Malignant Neoplasms

The signs and symptoms of malignant sinonasal neoplasms largely depend on their location, size, extent, and the stage of the disease. Early symptoms can be vague and mimic benign conditions like rhinitis or sinusitis, often leading to diagnostic delays.

Common symptoms include:

- Unilateral Nasal Obstruction: Often progressive and persistent.

- Nasal Discharge: Frequently unilateral, may be purulent, serosanguineous (blood-tinged), or frankly bloody (epistaxis). Fetid odor may develop with tumor necrosis.

- Impaired Sense of Smell (Hyposmia/Anosmia): Especially if the tumor is located in the upper nasal cavity near the olfactory receptors.

- Facial Pain or Pressure: Persistent pain in the face, cheek, or forehead.

- Dental Symptoms: Toothache (especially upper teeth), loose teeth, or swelling/ulceration in the gum region or hard palate if the tumor invades the maxilla.

- Orbital Symptoms (with orbital invasion):

- Proptosis (bulging of the eyeball)

- Diplopia (double vision)

- Limitation of eye movement

- Visual impairment or loss

- Epiphora (excessive tearing)

- Facial Swelling or Asymmetry: Changes in the shape of the nose or face.

- Neuralgic Pain: Due to nerve involvement.

- Headache: Can intensify as the disease progresses.

- Meningeal Symptoms: If the tumor invades the cranial cavity (e.g., severe headache, altered mental status, cranial nerve palsies).

- Constitutional Symptoms (in later stages): Weight loss, fatigue, cachexia.

- Regional Lymphadenopathy: Swollen lymph nodes in the neck, indicating metastasis.

Malignant tumors often disrupt multiple physiological functions of the nose. Besides olfactory and respiratory impairment, the excretory function of the nasal mucosa may be altered, leading to excessive mucus secretion due to irritation of mucous glands. Ciliary function, mucosal sensitivity, absorptive capacity, and resonator function are also commonly impaired. Trigeminal sensitivity may decrease alongside olfactory sensitivity. Olfactory thresholds often increase markedly (2-3 times the norm) even at the beginning of the disease.

A history of previous nasal surgeries (e.g., polypectomy, polypoethmoidotomy) might be present, as tumors can sometimes mimic the appearance of benign polyps. However, features suggestive of malignancy include a tuberous or irregular surface, friability (bleeds easily on contact), fixation to underlying tissues, evidence of bone destruction, rapid growth, and extension beyond the nasal cavity or sinuses.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Early diagnosis is crucial but often challenging. A high index of suspicion is needed for persistent unilateral nasal symptoms.

- Thorough Head and Neck Examination: Including palpation for facial swelling and lymph nodes.

- Nasal Endoscopy: Essential for detailed visualization of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, allowing for assessment of the tumor's appearance and extent.

- Biopsy: A biopsy of the suspicious lesion, usually performed under endoscopic guidance, is mandatory for definitive histological diagnosis. Fine needle aspiration (FNA) may be used for accessible neck nodes.

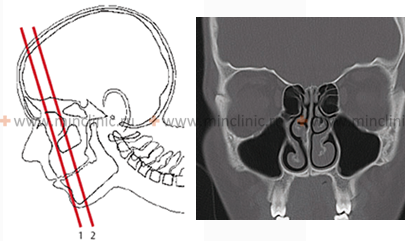

- Imaging Studies:

- CT Scan: Excellent for delineating bony destruction, tumor extent within sinuses, and involvement of adjacent bony structures.

- MRI: Superior for assessing soft tissue extension, perineural spread, dural involvement, and differentiating tumor from retained secretions or inflammation. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI are often used.

- PET-CT Scan: May be used for staging, detecting distant metastases, or assessing treatment response.

- Further Investigations: Depending on suspected tumor type and staging, further tests like chest X-ray/CT, liver function tests, etc., may be needed to evaluate for distant metastases. Examination by an ophthalmologist is crucial if orbital involvement is suspected (visual acuity, fields, fundus examination).

Malignant tumors must be differentiated from benign conditions like severe chronic sinusitis with polyposis, fungal sinusitis, granulomatous diseases (tuberculosis, Wegener's granulomatosis/GPA), or benign tumors. At the very beginning of development, malignant tumors can be asymptomatic or masked by symptoms of simple rhinitis. Distinguishing from tuberculosis may require specific stains and cultures in addition to histology.

Sometimes a tumor may present as an ulcer with a foul, offensive discharge. The tumor's appearance can change after a biopsy or during radiation therapy (shrinking), which needs to be considered in treatment planning. Objective examination data from rhinopneumometry, olfactometry, and endophotography can aid in diagnostics and documentation.

Patients often seek help in later stages when classic symptoms like nasal bleeding, fetid odor, facial deformity, exophthalmos, or tumor disintegration appear. An enlarged Jacobson's organ or various septal deformities with mucosal inflammation should always raise suspicion. Malignant tumors can sometimes mimic benign angiomas, papillomas, or even bullae (large air cells).

Osteomyelitis of nasal bones or periosteal inflammation can resemble a tumor. A malignant ethmoid sinus tumor might look like a mucopyocele. Quincke's edema (angioedema) of the orbit and eyelids can also present with swelling similar to a tumor. Malignant tumors of the naso-orbital region are particularly challenging. Growth from the nasal cavity/ethmoids often displaces the eyeball outward and anteriorly; from the frontal sinus, outward; from the maxillary sinus, upward and outward; and from the sphenoid sinus, anteriorly. Even subtle exophthalmos or diplopia can indicate orbital invasion.

In children aged 1-2 years, sarcomas (especially round-cell type) can grow extremely rapidly, with the tumor process becoming advanced within 1-2 months, emphasizing the need for oncological vigilance in pediatric practice. Polymorphic-cell sarcomas invade the orbit quickly, and round- and small-cell sarcomas are often more malignant than large-cell types, readily spreading from the nose into sinuses.

Radiographs can sometimes show the direction of displacement of bony walls, indicating the origin of tumor growth (e.g., from orbit to nasal cavity or vice versa). CT and MRI provide much more detailed information.

Sometimes malignant tumors of the nose can visually resemble typical benign formations like angiomas, papillomas, or nasal polyps, or even an enlarged air cell (bulla), necessitating careful diagnostic evaluation including biopsy.

Treatment Approaches for Malignant Neoplasms of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses

The treatment plan for malignant sinonasal tumors is formulated only after definitive histological diagnosis and comprehensive staging. A multidisciplinary team approach is essential. Recommended treatment typically involves a combination of modalities:

- Surgery: Surgical resection with clear margins is the mainstay for many operable tumors. This can range from endoscopic removal for early-stage or limited tumors to more extensive open approaches (e.g., lateral rhinotomy, midface degloving, craniofacial resection) for advanced disease.

- Radiation Therapy: Can be used as primary treatment for certain tumors (e.g., lymphomas, some sarcomas), postoperatively to eradicate residual disease or reduce recurrence risk, or palliatively for inoperable tumors. Advanced techniques like Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy (IMRT) help target the tumor while sparing normal tissues.

- Chemotherapy: May be used in various settings:

- Neoadjuvantly (before surgery or radiation) to shrink the tumor.

- Concurrently with radiation therapy (chemoradiation) to enhance its effects.

- Adjuvantly (after surgery or radiation) to treat micrometastases.

- Palliatively for metastatic or unresectable disease.

- Targeted Therapy and Immunotherapy: Emerging options for specific tumor types based on molecular profiling.

For inoperable nasal tumors, treatment focuses on radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and palliative measures. Palliative interventions may include debulking surgery to relieve obstruction, pain management, or ligation/embolization of large adducting blood vessels (e.g., external carotid arteries) to control bleeding. Despite aggressive treatment, malignant sinonasal tumors often have a guarded prognosis and a tendency for recurrence, sometimes months or even years later.

Rare Nasal Tumors: Esthesioneuroblastoma and Chemodectoma

Esthesioneuroblastoma (Olfactory Neuroblastoma)

Esthesioneuroblastoma is a rare malignant tumor arising from the olfactory neuroepithelium in the upper nasal cavity. It can occur in both children and adults. These tumors often recur, sometimes with a long delay (7-11 years after initial treatment). Metastases can occur to cervical lymph nodes, mediastinum, lungs, pleura, parotid gland, and other sites. Esthesioblastoma is usually localized in the region of the superior turbinate but can spread to the nasopharynx and often causes local destruction of the ethmoid sinus. The tumor's appearance varies from grayish-brown to dark red, and its consistency can be soft, dense, spongy, or polypoid, sometimes filling one half of the nose. Symptoms include progressive nasal obstruction, epistaxis, smell disorders (hyposmia/anosmia), and sometimes swelling at the root of the nose, lacrimation, or localized pain. Spread to adjacent structures causes corresponding symptoms. The prognosis is serious due to high recurrence and metastatic potential.

Chemodectoma (Paraganglioma)

Chemodectoma, also known as paraganglioma, is a rare neuroendocrine tumor arising from paraganglia (chemoreceptor cells). While often originating from the carotid body (at the bifurcation of the common carotid artery), chemodectomas can occur in various locations, including the head and neck region along cranial nerves (e.g., tympanic nerve - glomus tympanicum, vagus nerve - glomus vagale, glossopharyngeal nerve, intermediate nerve) or in organs with well-developed sympathetic innervation. These tumors are also referred to as "glomus tumors" or "nonchromaffinic paragangliomas." Paraganglia are considered by some to be sympathetic nodes, receptor devices, or glands, located in many parts of the body.

Chemodectomas typically grow slowly, but rapid infiltrative growth is also possible. Malignant variants, though histologically sometimes showing only mild signs of malignancy (e.g., slight cellular atypia, rare mitoses), can occur. The tumor often has a pronounced capsule. Despite exophytic growth, it can destroy surrounding tissues and spread to adjacent organs and cavities. Metastases to regional lymph nodes and distant organs are possible, though less common than with other malignancies.

The main and most effective treatment methods for chemodectomas are surgical excision and, in some cases, radiation therapy (especially for unresectable or recurrent tumors, or as an adjunct). Chemical cauterization methods (e.g., concentrated silver nitrate, carbonic acid "snow") are generally ineffective and associated with high recurrence rates.

Sarcoidosis of the Nose (Benign-Beck-Schaumann Disease)

Clinical Forms and Manifestations

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease of unknown etiology, characterized by the formation of non-caseating granulomas in various organs. While the lungs and intrathoracic lymph nodes are most commonly affected, nasal involvement can occur and is more common in adults. It may be associated with involvement of extrathoracic lymph nodes, tonsils, and parotid salivary glands.

Nasal sarcoidosis can present in several forms:

- Polypoid Non-Ulcerating Lesions: Tumorous growths of a rather dense consistency.

- Nodular Form: Dense nodules, the size of a pinhead or millet grain, often surrounded by an area of hyperemia (redness).

- Diffuse Infiltrative Form: Characterized by diffuse infiltration of the nasal mucosa, often with abundant mucous secretion.

Typically, mucosal involvement in nasal sarcoidosis precedes cutaneous manifestations and can mimic changes seen in atrophic rhinitis, with dryness, crusting, and obstruction. The bones of the nose, as well as its soft tissues, can be affected either in isolation or concurrently. Sarcoidosis affecting the nasal bones can lead to a tumor-like change at the root of the nose, causing it to become thicker and wider ("lupus pernio" is a specific cutaneous form that can involve the nose).

Differential Diagnosis and Fibrous Dysplasia

Nasal sarcoidosis needs to be differentiated from generalized tuberculosis of the nasal mucosa and chronic atrophic processes. Diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy showing non-caseating granulomas, exclusion of other granulomatous diseases (like infections), and often evidence of systemic involvement. X-ray examination may reveal changes in affected bones resembling cystic osteitis.

Fibrous Dysplasia is a benign bone disorder, typically affecting children and adolescents (more common in girls), considered a malformation of bone development, possibly originating in the embryonic period or postnatally. It's often referred to as a borderline tumor. The affected bone has a "swollen" or "ground-glass" appearance and is usually painless. Fibrous dysplasia can affect the nose and paranasal sinuses (maxillary, ethmoid). Multiple bone involvement in the facial skeleton and skull is possible. Radiographically, focal fibrous dysplasia shows well-defined zones of radiolucency with sclerotic borders. Thinning of the cortical layer is typical, and sometimes a cellular or cystic appearance is noted. Growth is often more intensive during childhood and adolescence and may stabilize or stop with skeletal maturity.

Surgical Approaches for Sinonasal Tumors

The surgical approach for various tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses depends on their nature (benign/malignant), size, location, extent, and the patient's age and overall health. Common approaches include:

- Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (ESS): The preferred method for many benign tumors and early-stage malignant tumors. It is minimally invasive, performed through the nostrils using endoscopes and specialized instruments.

- External Approaches: For larger tumors or those with extensive involvement, open surgical approaches may be necessary.

- Lateral Rhinotomy: An incision along the side of the nose.

- Midface Degloving: Provides wide exposure without external facial incisions by elevating the facial soft tissues from the underlying bone.

- Caldwell-Luc Procedure: An approach to the maxillary sinus through an incision under the upper lip in the canine fossa. This may be used for tumors localized deep within the maxillary sinus. After local anesthesia, a horizontal incision of the mucous membrane and periosteum is made from the frenulum to the level of the 2nd large molar. Soft tissues are elevated, and a portion of the facial (anterior) wall of the maxillary sinus is resected to remove the tumor or pathological formation. An anastomosis (opening) is then created between the sinus and the nasal cavity, typically in the region of the inferior nasal meatus. The anastomosis should be as wide as possible, without a threshold between the nasal floor and the sinus floor.

- Craniofacial Resection: For tumors involving the skull base, combining neurosurgical and ENT approaches.

With large tumors, surgery might be complemented by wider resection of the medial maxillary sinus wall, the edge of the piriform aperture, and involved turbinates to ensure complete removal and adequate drainage. The goal is always complete tumor removal with clear margins while preserving function and cosmesis as much as possible.

Differential Diagnosis of Unilateral Nasal Mass/Obstruction

A unilateral nasal mass or persistent unilateral obstruction should always be thoroughly investigated to rule out malignancy, especially in adults. Key differential diagnoses include:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Benign Sinonasal Tumors (e.g., Inverted Papilloma, Angioma, Osteoma) | Slow growth, specific imaging features (e.g., bony density for osteoma, characteristic MRI for papilloma). Biopsy confirms benign nature. |

| Malignant Sinonasal Tumors (e.g., SCC, Adenocarcinoma, Sarcoma) | Rapid growth, pain, epistaxis, cranial nerve involvement, bony erosion on imaging. Biopsy confirms malignancy. |

| Nasal Polyps (Unilateral) | Often associated with chronic rhinosinusitis. Antrochoanal polyp is a common unilateral polyp in younger individuals. Appearance on endoscopy. |

| Mucocele/Pyocele | Smooth, expansile lesion on imaging, often causing bony remodeling or erosion. Contents are mucus or pus. |

| Chronic Granulomatous Diseases (e.g., Sarcoidosis, GPA/Wegener's, Tuberculosis, Fungal Infections) | Crusting, septal perforation, saddle nose deformity (in advanced cases). Systemic symptoms may be present. Biopsy shows granulomas or specific infectious agents. |

| Deviated Nasal Septum with Severe Obstruction | Visible septal deformity. No distinct mass. |

| Encephalocele/Meningoencephalocele | Congenital; pulsatile mass, may increase with crying/straining. Connection to intracranial space seen on imaging. |

| Foreign Body with Granulation Tissue | History (often in children), unilateral foul discharge, granulation tissue around the object. |

Prognosis and When to Seek Specialist Care

The prognosis for benign sinonasal tumors is generally good after complete surgical removal, although some types (like inverted papilloma) have a risk of recurrence.

The prognosis for malignant neoplasms of the nose and paranasal sinuses is often poor, particularly for advanced-stage disease, due to their aggressive nature, proximity to vital structures, and tendency for late diagnosis. Early detection and multidisciplinary treatment offer the best chance of cure or control.

It is crucial to consult an ENT specialist promptly if any of the following symptoms occur, as they could indicate a sinonasal tumor or other serious condition:

- Persistent unilateral nasal obstruction.

- Recurrent or unexplained epistaxis (nosebleeds), especially if unilateral.

- Persistent facial pain, pressure, or numbness.

- Swelling or deformity of the face or nose.

- Changes in vision (e.g., double vision, proptosis, decreased acuity).

- Persistent, unexplained loose upper teeth.

- A non-healing sore or ulcer inside the nose.

- Unexplained loss of smell (anosmia).

- Swollen lymph nodes in the neck.

Early diagnosis and treatment by a specialized team are paramount for optimizing outcomes in patients with tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses.

References

- Barnes L, Eveson JW, Reichart P, Sidransky D, eds. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Head and Neck Tumours. Lyon: IARC Press; 2005.

- Dulguerov P, Jacobsen MS, Allal AS, Lehmann W, Calcaterra T. Nasal and paranasal sinus carcinoma: are we making progress? A systematic review of 2206 cases. Cancer. 2001 Nov 15;92(10):2716-27.

- Lund VJ, Stammberger H, Nicolai P, et al. European position paper on endoscopic management of tumours of the nose, paranasal sinuses and skull base. Rhinol Suppl. 2010 Jun;(22):1-143.

- Myers EN, Fernau JL, Johnson JT, Tabb HG, D'Amico F. Management of inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope. 1990 Jun;100(6):613-6.

- Bradley PJ. Sarcoidosis of the head and neck. J R Soc Med. 2000 Feb;93(2):60-4.

- Hanna E, DeMonte F, Ibrahim S, Roberts D, Levine N, Kupferman M. Endoscopic resection of sinonasal cancers with and without craniotomy: oncologic results. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Dec;135(12):1219-24.

- Spector JG, Gado M. Osteomas of the paranasal sinuses. Laryngoscope. 1982 Jul;92(7 Pt 1):768-73.

- Resto VA, Deschler DG. Esthesioneuroblastoma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008 Feb;41(1):271-85, viii.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis