Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Understanding Deviated Nasal Septum (DNS) and Nasal Bone Deformities

- Symptoms and Impact of Nasal Deformities

- Diagnosing Deviated Septum and Nasal Deformities

- Types and Classifications of Nasal Septum Deformities

- Treatment Options for Deviated Nasal Septum and Nasal Bone Deformities

- Potential Complications and Considerations

- When to Consult an ENT Specialist

- References

Understanding Deviated Nasal Septum (DNS) and Nasal Bone Deformities

The Nose: Anatomy, Aesthetics, and Vital Functions

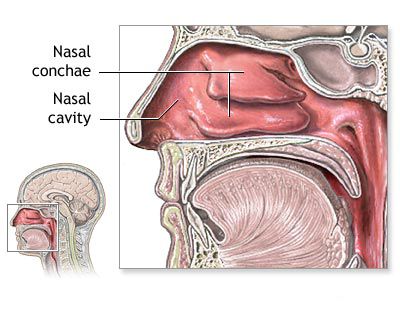

The nose is a prominent and complex anatomical feature of the face, serving as a crucial component of the upper respiratory tract and playing a significant role in facial aesthetics. Deformities of the external nose, whether congenital (such as a prominent nasal bridge, an overly broad nose, or a large dorsal hump) or acquired, can cause considerable psychological discomfort and impact self-esteem. Acquired traumatic deformities are frequently the result of domestic injuries, sports-related accidents, or traffic collisions.

Beyond its aesthetic role, an impaired external shape of the nose often signifies underlying structural issues that can compromise its numerous vital functions. The nose is responsible for:

- Respiration: Providing the primary pathway for air entry.

- Air Conditioning: Cleaning, warming, and humidifying inhaled air before it reaches the lungs. The inspiratory resistance created by the nasal cavity is essential for generating negative intrathoracic pressure during inhalation, which enhances pulmonary ventilation and venous return to the heart.

- Olfaction: Housing the sensory receptors for the sense of smell, which is vital for detecting hazards, enjoying food, and social interaction.

- Phonation: Contributing to voice resonance. A balanced anatomical structure of the nose is necessary for normal voice tone.

Therefore, impaired nasal breathing due to deformities not only leads to chronic hypoxia (reduced oxygen supply) but can also contribute to the development or exacerbation of diseases affecting the lungs, upper respiratory tract, and even the cardiovascular system.

Aesthetically, the nose is a central feature by which facial harmony is judged. A face is often considered harmonious when the heights of its upper, middle, and lower thirds are roughly equal. The length of the nose typically defines the height of the middle third of the face.

Causes of Nasal Septum Deviation and Bone Deformities

Congenital and acquired traumatic deformations of the nasal bridge and septum often not only affect facial appearance, causing psychological distress, but also lead to significant functional impairments. The etiology of nasal septum deformities (such as curvature, a septal spur, or a ridge) and external nasal bone deformities can be attributed to three main categories of factors:

- Physiological (Developmental): A deviated nasal septum is frequently a result of differential growth rates between the septum itself (composed of cartilage and bone) and the surrounding bony facial framework (the maxilla and ethmoid bones) during childhood and adolescence. If the septum grows faster than the space available to accommodate it, it may buckle or deviate. Some researchers suggest that septal deformation can begin as early as 7 years of age, or even earlier. A hereditary predisposition to these growth patterns may also play a role.

- Traumatic: Injuries to the nose, whether from direct blows, falls, or other accidents, are a very common cause of both septal deviations and external nasal bone fractures and deformities. Improper healing or fusion of bone fragments after a nasal fracture can lead to lasting structural changes. Birth trauma during delivery can also, in some instances, cause septal dislocation or deviation in newborns (reported in 5-15% of newborns, often affecting the anteroinferior region).

- Compensatory: A septal deviation can sometimes develop or worsen as a compensatory mechanism due to pressure exerted on the nasal septum by other intranasal structures. For example, chronically enlarged turbinates (hypertrophic turbinates), large nasal polyps, or intranasal tumors can push the septum to the opposite side.

From an evolutionary (phylo- and ontogenetic) perspective, the formation of a deviated nasal septum is considered by some to be an almost inevitable consequence of human evolution, linked to changes in skull base structure, the autonomous growth of septal cartilage, altered relationships between the quadrangular cartilage and the vomer, and the relative regression of the maxillo-facial skeleton compared to the expanding neurocranium.

Symptoms and Impact of Nasal Deformities

A deviated nasal septum (DNS) and external nasal bone deformities can lead to a variety of symptoms and functional impairments. The severity and type of symptoms often depend on the degree and location of the deviation or deformity.

- Nasal Obstruction: This is the most common symptom, characterized by difficulty breathing through one or both nostrils. It may be constant or more noticeable on one side.

- Mouth Breathing: Chronic nasal obstruction often forces individuals to breathe through their mouth, especially during sleep or exertion. This can lead to dry mouth, chapped lips, and an increased risk of dental problems and throat irritation.

- Snoring and Sleep Disturbances: Impaired nasal airflow can contribute to snoring and, in more severe cases, may be a factor in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), leading to poor sleep quality and daytime fatigue.

- Headaches: Contact points where a deviated septum, spur, or ridge presses against the lateral nasal wall (particularly the turbinates) can trigger pressure headaches or facial pain, sometimes referred to as "contact point headaches" or Sluder's neuralgia. Headaches are often localized to the supraorbital region.

- Recurrent Sinus Infections (Sinusitis): A deviated septum can obstruct sinus drainage pathways, creating an environment conducive to bacterial growth and leading to recurrent or chronic sinusitis.

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis): The altered airflow can cause drying and crusting of the nasal mucosa over the deviated portion of the septum, making it more prone to bleeding. Sharp septal spurs can also traumatize the mucosa.

- Facial Pain or Pressure: A feeling of pressure or fullness in the face, particularly around the nose and sinuses.

- Decreased Sense of Smell (Hyposmia/Anosmia): Severe obstruction can impair the ability of odor molecules to reach the olfactory receptors high in the nasal cavity.

- Changes in Voice (Rhinolalia): Altered nasal resonance can result in a hyponasal (denasal) voice quality.

- Dry Pharynx and Throat Irritation: Due to chronic mouth breathing.

- Occasional Spasms of the Glottis (Laryngospasm): Rarely, severe nasal issues might reflexively contribute to laryngeal hypersensitivity.

Prolonged and significant impaired nasal breathing, especially during developmental years, can lead to changes in facial skeletal development. This may manifest as a high-arched or "gothic" palate, an "adenoid-type" facial appearance (long face, open mouth), and abnormal development or malocclusion of the upper teeth. The chronic oxygen starvation (hypoxia) resulting from difficult nasal breathing can also negatively impact overall physical and cognitive performance.

It's important to recognize that the severity of symptoms does not always correlate directly with the degree of anatomical deviation visible on examination. Some individuals with significant deviations may experience minimal symptoms, while others with relatively minor deformities may have substantial complaints.

Diagnosing Deviated Septum and Nasal Deformities

A thorough diagnosis of a deviated nasal septum and associated nasal bone deformities involves a combination of a detailed medical history, a comprehensive physical examination, and sometimes imaging studies.

- Medical History: The physician will inquire about the onset and nature of symptoms (nasal obstruction, headaches, snoring, nosebleeds, etc.), any history of nasal trauma (even in childhood, which may be forgotten), previous nasal surgeries, and any related medical conditions. A family history of similar nasal issues may also be relevant.

- Physical Examination:

- External Nasal Examination: The external appearance of the nose is assessed for any visible asymmetry, deviation, depressions, humps, or other deformities of the nasal bones and cartilages. The physician will palpate the nasal bridge and tip.

- Anterior Rhinoscopy: This involves using a nasal speculum and a bright light source to directly visualize the anterior (front) portions of the nasal cavities. This allows for assessment of the position of the nasal septum, the size and condition of the nasal turbinates, the presence of mucus or pus, and any obvious polyps or masses.

- Nasal Endoscopy: For a more detailed and comprehensive view of the entire nasal cavity, including the posterior septum, sinus openings (ostiomeatal complex), and nasopharynx, a rigid or flexible nasal endoscope may be used. This thin tube with a camera and light source provides a magnified view on a monitor. Topical anesthetic and decongestant sprays are usually applied to the nasal passages before endoscopy to improve visualization and patient comfort.

- Functional Assessment: The physician may assess nasal airflow subjectively by observing breathing patterns or objectively using techniques like acoustic rhinometry or rhinomanometry, though these are not routinely performed in all settings.

- Imaging Studies:

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan: A CT scan of the paranasal sinuses is not always necessary for diagnosing a deviated septum alone but may be ordered if chronic sinusitis is suspected, if there is a complex traumatic deformity, or to evaluate the extent of septal deviation in the posterior regions and its impact on sinus anatomy, especially pre-operatively.

- X-rays: Simple X-rays are generally less useful for evaluating septal deviations but might be used in cases of acute nasal trauma to identify fractures.

The differential diagnosis between congenital, post-traumatic, and compensatory deformities relies more on the rhinoscopic picture and the specific characteristics of the deformity (e.g., sharp fracture lines in trauma) than solely on the patient's anamnesis, as a history of early childhood trauma may not always be reliably recalled.

Types and Classifications of Nasal Septum Deformities

Nasal septum deformities can vary widely in their shape, location, and severity. Several classifications have been proposed to categorize these deviations, though a universally accepted, comprehensive system remains elusive due to the vast diversity of presentations. Some common ways to describe and classify septal deformities include:

- Based on Severity of Deviation:

- Grade 1: Slight deviation of the septum from the midline.

- Grade 2: Moderate deviation, where the septum extends approximately midway between the midline and the lateral nasal wall.

- Grade 3: Severe deviation, where the deformed part of the septum makes contact with the lateral nasal wall.

- Based on Shape of Deviation:

- C-shaped deviation: A simple curve of the septum to one side.

- S-shaped deviation: A more complex curve, where the anterior part deviates to one side and the posterior part deviates to the opposite side (or vice-versa).

- Septal Spur: A sharp, bony or cartilaginous projection extending from the septum, often impinging on the lateral nasal wall or turbinates.

- Septal Ridge: A linear, elongated prominence along the septum.

- Dislocation of the Caudal (Anterior) Septum: The front edge of the septal cartilage is displaced from its normal position in the columella, often visible at the nostril entrance.

- Thickening or "Hump": Localized thickening of the septum, commonly at the junction of the quadrangular cartilage and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, which can obstruct the upper nasal passages.

- "Wrinkled" or Complex Septum: Multiple fracture lines or bends, often resulting from severe trauma, where fragments may overlap or be angulated in various directions.

One proposed classification detailed 7 types based on vertical ridges, horizontal ridges, and S-shaped bends, but this still struggled to encompass all variations. Many complex deformities, particularly post-traumatic ones with multiple fracture lines, are difficult to fit neatly into simple classifications.

Clinically, it's often more practical to describe the deviation by its location (anterior, posterior, superior, inferior), the structures involved (cartilage, bone, or both), and its impact on nasal airflow and contact with lateral nasal structures. The degree of difficulty in nasal breathing is a primary consideration. Deviated septa, especially ridges and spurs in contact with turbinates, can trigger pathological reflexes, affecting not only local nasal function but also potentially having broader systemic reflex effects. Conditions like chronic tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and laryngitis can be aggravated by the impaired nasal breathing caused by a DNS, making septal surgery a consideration in these patients.

Common Types of Septal Deviations and Their Characteristics

| Type of Deviation | Description | Common Symptoms/Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior (Caudal) Dislocation | The front edge of the septal cartilage is displaced from the columella, often visible externally. | Unilateral or bilateral nostril obstruction, cosmetic concerns, altered airflow at nasal entrance. |

| C-Shaped Deviation | A simple curve of the septum to one side along its length. | Unilateral nasal obstruction on the side of convexity, compensatory turbinate hypertrophy on the concave side. |

| S-Shaped Deviation | A double curve, with deviation to one side anteriorly and the opposite side posteriorly (or superiorly/inferiorly). | Bilateral, often alternating, nasal obstruction. More complex airflow disruption. |

| Septal Spur | A sharp, localized projection of bone or cartilage. | Contact headaches, localized pain, epistaxis (nosebleeds) if mucosa is irritated, obstruction, sinusitis if blocking sinus ostia. |

| Septal Ridge | An elongated, linear prominence along the septum. | Similar to spurs, can cause obstruction and contact phenomena depending on size and location. |

| Basal Crest Thickening | Thickening or deviation at the base of the septum where it meets the nasal floor (maxillary crest). | Obstruction of the lower nasal airway, may affect airflow to inferior turbinates. |

| High Septal Deviation | Deviation in the superior part of the septum, near the olfactory area or middle meatus. | May affect sense of smell, obstruct middle meatus leading to sinusitis, potential for contact headaches. |

It's important to note that these types often coexist or combine, creating complex, individualized patterns of septal deformity. Changes in the nasal mucosa due to altered airflow, such as chronic inflammation or dryness, can also negatively impact the function of the nasolacrimal duct (tear duct).

Treatment of Deviated Nasal Septum (DNS) and Nasal Bones Deformation

The approach to treating a deviated nasal septum and associated nasal bone deformities depends on the severity of symptoms, the degree of anatomical abnormality, and the patient's individual needs and preferences. While many individuals have some degree of septal deviation, treatment is generally only indicated when it causes significant functional or aesthetic concerns.

Conservative Management

For mild symptoms, or while awaiting definitive surgical correction, conservative measures may provide some relief, although they do not correct the underlying structural problem:

- Nasal Saline Rinses/Sprays: Help to moisturize the nasal passages, clear mucus, and reduce mucosal irritation.

- Nasal Decongestant Sprays: Can provide temporary relief from congestion but should be used sparingly (no more than 3-5 days) to avoid rebound congestion (rhinitis medicamentosa).

- Nasal Corticosteroid Sprays: Can help reduce inflammation of the nasal mucosa and turbinates, which may improve airflow around a deviated septum, especially if there's a coexisting allergic or non-allergic rhinitis component.

- Antihistamines: If allergies contribute to nasal symptoms, antihistamines may be helpful.

These measures primarily address mucosal symptoms and do not alter the fixed anatomical deformity.

Surgical Correction: Septoplasty and Rhinoplasty

The definitive treatment for a symptomatic deviated nasal septum is a surgical procedure called **septoplasty**. The goal of septoplasty is to straighten the nasal septum, reposition it in the midline, and remove any obstructive spurs or ridges, thereby improving nasal airflow and relieving associated symptoms.

If there are also external nasal bone deformities or aesthetic concerns about the shape of the nose, septoplasty is often combined with **rhinoplasty**. This combined procedure is known as **septorhinoplasty**. Rhinoplasty aims to reshape the external nasal bones and cartilages to improve the nose's appearance and, in many cases, its function.

Indications for surgical intervention include:

- Persistent and bothersome nasal obstruction unresponsive to medical therapy.

- Recurrent sinusitis related to septal deviation.

- Recurrent nosebleeds caused by septal deformity.

- Significant contact point headaches.

- As part of treatment for snoring or obstructive sleep apnea if DNS is a contributing factor.

- To correct external nasal deformities for functional or aesthetic reasons.

- To gain access for other intranasal surgeries (e.g., sinus surgery, tumor removal).

Septoplasty is typically performed entirely through the nostrils, leaving no external scars. The surgeon makes an incision inside the nose, lifts the mucous membrane lining (mucoperichondrium and mucoperiosteum) off the septal cartilage and bone, reshapes or removes the deviated portions, and then repositions the mucosal flaps. Various techniques exist, including traditional approaches and more modern endoscopic techniques that allow for better visualization and more precise correction. The maxillaria-premaxillary approach, for example, involves peeling the mucosa on one side for mobilization and fixation, sometimes creating a channel at the nasal floor for resecting deformed bony parts, aiming to preserve the quadrangular cartilage.

Modern Surgical Techniques

While many septoplasty techniques have been proposed over the years, the focus today is on approaches that are both effective and physiological, preserving as much of the natural septal framework as possible. Each septal deformity often requires a customized surgical approach.

- Endoscopic Septoplasty: Utilizes an endoscope for enhanced visualization, allowing for more targeted correction of posterior deviations and spurs with minimal disruption to surrounding tissues.

- Laser Septochondroplasty: May be used in specific cases for reshaping cartilage segments, though its application is limited and not suitable for all types of deviations.

- Ultrasonic Septoplasty (Piezosurgery): Employs ultrasonic vibrations for precise bone cutting and cartilage reshaping, potentially reducing trauma to soft tissues. This can be effective for both cartilaginous and bony deformities.

The aim of these modern techniques is to achieve a stable, straight septum with restored nasal breathing and preserved structural integrity, minimizing complications.

Post-Operative Care and Recovery

Recovery after septoplasty or septorhinoplasty varies but generally involves:

- Nasal Packing/Splints: Nasal packing or internal splints may be placed at the end of surgery to support the septum, minimize bleeding, and prevent adhesions. These are usually removed within a few days to a week.

- Pain Management: Discomfort is typically managed with oral pain medication.

- Nasal Congestion and Swelling: Expected for several days to weeks due to internal swelling.

- Activity Restrictions: Strenuous activities, heavy lifting, and nose blowing are usually restricted for a few weeks.

- Nasal Saline Rinses: Recommended to keep the nasal passages clean, moist, and free of crusts during healing.

- Follow-up Appointments: Essential for monitoring healing, removing any packing or splints, and cleaning the nasal passages.

Full healing and the final functional and aesthetic outcome can take several weeks to months. Significant improvement in nasal breathing is usually experienced once the initial swelling subsides.

Potential Complications and Considerations

Septoplasty, while generally a safe and effective procedure, carries potential risks and complications, as with any surgery. These can include:

- Bleeding (Epistaxis): Some bleeding is normal, but excessive bleeding may require intervention.

- Infection: Rare, but can occur. Antibiotics may be prescribed prophylactically or to treat an infection.

- Septal Hematoma: A collection of blood within the septal flaps, which requires drainage to prevent cartilage damage or septal abscess.

- Septal Perforation: A hole in the nasal septum, which can cause crusting, whistling, or bleeding. This risk depends on the complexity of the deviation and surgical technique.

- Numbness: Temporary numbness of the front teeth, upper lip, or tip of the nose can occur due to nerve irritation.

- Persistent or Recurrent Symptoms: In some cases, nasal obstruction may persist or recur, occasionally requiring revision surgery.

- Changes in Sense of Smell or Taste: Usually temporary.

- Scarring and Adhesions (Synechiae): Internal scar tissue can form between the septum and lateral nasal wall, potentially causing obstruction.

- Cosmetic Changes: While septoplasty itself is internal, rarely, changes to the external nasal appearance (e.g., saddle nose deformity if too much cartilage is removed) can occur, especially with aggressive techniques. This is a greater consideration in septorhinoplasty.

- Atrophy of Nasal Mucosa (Subatrophic Rhinitis): Can result from impaired vascularization or lymphatic drainage, especially with older, more aggressive surgical approaches that disrupt the trophic supply to the mucosa.

The surgeon's experience, meticulous technique, and careful patient selection are crucial in minimizing these risks. It is important to have a thorough discussion with the ENT surgeon about the potential benefits and risks before proceeding with surgery.

When to Consult an ENT Specialist

Individuals experiencing symptoms suggestive of a deviated nasal septum or nasal bone deformity should consider consulting an Ear, Nose, and Throat (ENT) specialist if:

- Nasal obstruction is persistent and significantly impacts daily life, sleep, or exercise.

- There are recurrent or chronic sinus infections.

- Frequent nosebleeds occur.

- Chronic headaches or facial pain are suspected to be related to nasal issues.

- Snoring or symptoms of sleep apnea are present.

- There are aesthetic concerns about the shape of the nose, especially after trauma.

- Conservative measures have failed to provide adequate relief.

An ENT specialist can provide an accurate diagnosis, discuss the severity of the condition, and recommend appropriate management options, including whether surgical intervention is warranted.

References

- Stoksted P. The physiologic and pathologic relationship between the nose and the lungs. Am J Rhinol. 1992;6(1):23-28.

- Mlynski G, Grützenmacher S, Plontke S, Mlynski B. The deviated nasal septum: a review of the literature, an evaluation of current concepts, and new hypotheses regarding its etiopathogenesis. HNO. 2005;53(5):401-410.

- Guyuron B, Uzzo CD, Scull H. A practical classification of septonasal deviation and an effective guide to septal surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(7):2202-2209.

- Dinis PB, Haider H. Septoplasty: long-term evaluation of results. Am J Otolaryngol. 2002;23(2):85-90.

- Ketcham AS, Han JK. Complications of septoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2010;43(4):895-903.

- Fettman N, Sanford T, Sindwani R. Surgical management of the deviated septum: techniques in septoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42(2):241-252.

- Most SP. Septoplasty: the S-shaped septum. Facial Plast Surg. 2007;23(4):253-258.

See also

Nasal cavity diseases:

- Runny nose, acute rhinitis, rhinopharyngitis

- Allergic rhinitis and sinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis

- Chlamydial and Trichomonas rhinitis

- Chronic rhinitis: catarrhal, hypertrophic, atrophic

- Deviated nasal septum (DNS) and nasal bones deformation

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis)

- External nose diseases: furunculosis, eczema, sycosis, erysipelas, frostbite

- Gonococcal rhinitis

- Changes of the nasal mucosa in influenza, diphtheria, measles and scarlet fever

- Nasal foreign bodies (NFBs)

- Nasal septal cartilage perichondritis

- Nasal septal hematoma, nasal septal abscess

- Nose injuries

- Ozena (atrophic rhinitis)

- Post-traumatic nasal cavity synechiae and choanal atresia

- Nasal scabs removing

- Rhinitis-like conditions (runny nose) in adolescents and adults

- Rhinogenous neuroses in adolescents and adults

- Smell (olfaction) disorders

- Subatrophic, trophic rhinitis and related pathologies

- Nasal breathing and olfaction (sense of smell) disorders in young children

Paranasal sinuses diseases:

- Acute and chronic frontal sinusitis (frontitis)

- Acute and chronic sphenoid sinusitis (sphenoiditis)

- Acute ethmoiditis (ethmoid sinus inflammation)

- Acute maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Chronic ethmoid sinusitis (ethmoiditis)

- Chronic maxillary sinusitis (rhinosinusitis)

- Infantile maxillary sinus osteomyelitis

- Nasal polyps

- Paranasal sinuses traumatic injuries

- Rhinogenic orbital and intracranial complications

- Tumors of the nose and paranasal sinuses, sarcoidosis