Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury

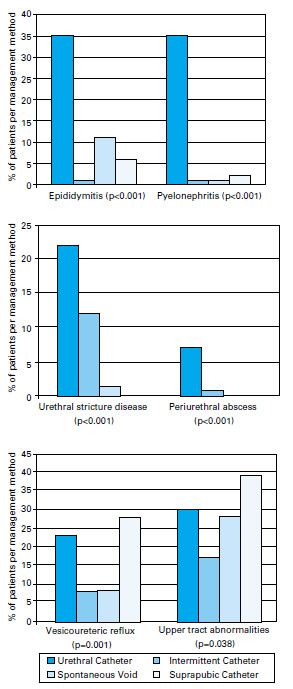

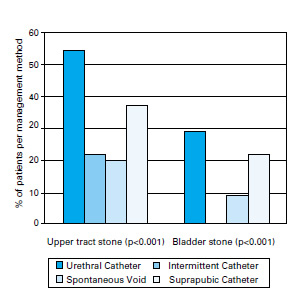

After spinal cord injury (SCI), dysfunctional voiding patterns soon emerge. These are usually characterised by hyperreflexic bladder contractions in suprasacral cord lesions and acontractile bladders in conus medullaris and cauda equina lesions. Quite apart from socially incapacitating incontinence, the resulting urodynamic abnormalities can lead to recurrent urinary tract infection (UTI), vesico-ureteric reflux, and upper tract dilatation and hydronephrosis. This results in long-term damage to the urinary tract, with eventual renal failure. Constant urological vigilance is therefore an essential part of management.

Aims of management:

- Preservation of renal function

- Continence

Early management

Intermittent catheterisation

Ideally, intermittent catheterisation begins on arrival in the spinal injuries unit, using a size 12–14 lubricated Nelaton catheter. Commercially available coated self-lubricating catheters are now widely available. Catheterisation is undertaken 4–6 hourly; by restricting fluid intake to maintain a urine output of around 1500 ml per day, bladder volumes should not exceed 400–500 ml per catheterisation.

Most patients will, however, have had a standard Foley catheter inserted at the admitting emergency department, often to measure hourly urine output as part of the general management of the seriously injured patient.

In practice, many will retain an indwelling catheter until about 12 weeks after injury, when formal urodynamic appraisal can be undertaken. Definitive bladder management can then be planned and initiated.

Intermittent urethral catheterisation:

- Clean technique

- 6-hourly programme

- Fluid restriction

- Treat significant UTI

Complications of urethral catheters:

- Infection

- Epididymo-orchitis

- Paraurethral gland abscess

- Urethral diverticulum/fistula

- Calculous/biofilm encrustation

- Recurrent blockage +/- dysreflexic attacks

- Urethral erosion (females)

- Traumatic hypospadias (males)

Tapping and expression

After a period of "spinal shock", involuntary detrusor activity is observed in most patients with suprasacral cord lesions. By about 12 weeks after injury, those patients who it is felt may manage without long-term catheters will have begun bladder training. In those with minimal detrusor-distal sphincter dyssynergia (DSD see below), suprapubic tapping and, if necessary, compression may be sufficient to empty the bladder. Tapping and compression continue until urinary flow ceases. The process is repeated every 2 hours.

When male patients begin to void, they wear condom sheaths attached to urinary drainage bags. Their fluid intake is no longer restricted, and the frequency of intermittent catheterisation is gradually reduced. Initially, the post "voiding" residual volume is checked daily, either by "in-out" catheters, or using a portable bladder scanner. When this is <100 ml on three consecutive occasions, bladder training is complete, and intermittent catheterisation is discontinued. The residual volume requires re-checking during the first year.

Indwelling catheterisation

In those patients unsuited to tapping and expression or intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC), consideration may be given to long-term indwelling catheterisation as a permanent method of bladder drainage.

Both short- and long-term indwelling catheters are convenient, but have risks and complications. Wheelchair-bound female patients with urethral catheters are especially prone to urethral erosion and such patients (especially if they have hyperreflexic bladders) are unsuitable for long-term urethral catheters, once they have mobilised. Women with strong bladder contractions may expel both balloon and catheter, causing a severe dilatation of the urethra. Early suprapubic catheterisation should be considered in this group.

In men, pressure necrosis at the external urethral meatus causes an increasing traumatic hypospadias and cleft penile urethra.

Urethral catheters should be as small as is compatible with good drainage, and should preferably be made of pure silicone. These catheters may be left in situ for 6–8 weeks.

Wherever possible, regular "cycling" of the bladder should take place, using a catheter valve to intermittently release urine. This helps to maintain bladder volume and compliance, though where detrusor activity is present, anticholinergic therapy is indicated. This is particularly important where the patient may be deemed eventually suitable for ISC.

Patients with indwelling catheters are prone to develop calculous blockage, and bladder washouts with water, saline or Suby-G solution are recommended on a weekly basis, especially if the urine is cloudy with sediment. A fluid intake of 2.5–3 L per day may help reduce the risk of calculous blockage and infection. Regular blockage should be investigated with cystoscopy and removal of any stone fragments.

Urine is cultured weekly, and at other times if indicated. Proteus sp. and Klebsiella are urea splitting organisms, and particularly important bacteria to eradicate. These infections and the resulting alkalisation are associated with a high incidence of "struvite" stone (calcium apatite and magnesium ammonium phosphate) formation in both the bladder and the upper tracts. Stag-horn calculi require early removal by percutaneous or open pyelolithotomy, before the infected stone results in the development of xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis and an inevitable nephrectomy. Percutaneous dissolution of struvite stone (e.g. with hemiacidrin) is sometimes successful.

Catheterised patients invariably develop colonised urine, usually with a mixed flora. Antibiotic therapy is not indicated here, unless the patient develops systemic signs of infection (including skin "marking").

Suprapubic catheterisation (SPC)

Patients with large acontractile bladders (capacity >500 ml) can be safely catheterised on the ward under local anaesthetic and cystodistension, using one of the commercially available introducing trocars and a 12 or 16 Ch Foley catheter. The poor "balloon memory" of pure silicone catheters may cause difficulty with subsequent removal, and coated latex may be the material of choice for suprapubic catheters. Care should be taken in selecting an appropriate suprapubic puncture site to avoid deep skin creases. In obese patients, and in those with small and hyperreflexic bladders, careful cystoscopic placement of the stab cystostomy trocar, or formal open cystostomy under general or spinal anaesthesia in the operating room is recommended. In this way, autonomic dysreflexia is avoided, and the risk of inadvertent small bowel injury is minimised.

SPC is increasingly used as a method of bladder drainage in the first few weeks after SCI, and is the personal preference of many patients in the long term. Fluid restriction is unnecessary — an intake of 3 litres per day may help reduce the risk of blockage.

Although SPC avoids risks to the urethra and allows greater sexual freedom, it shares many of the other unwanted side effects of permanent urethral catheterisation. Blockage by sediment, and in hyperreflexic patients, by lumenal compression and mucosal plugging results in "bypassing", and in high cord lesions, the associated bladder spasm frequently results in episodes of autonomic dysreflexia.

Intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC)

When intermittent catheterisation has been performed by the nursing staff as part of initial bladder management, ISC can start as soon as the patient sits up. Patients catheterise themselves with the aim of remaining continent between catheterisations, therefore avoiding the need to wear urinary drainage apparatus.

Patients with acontractile bladders are the most suitable candidates for ISC, though hyperreflexic detrusor activity is not a contraindication provided it is well controlled with anticholinergic therapy.

A "clean" but not sterile technique is employed, using 12–14 Ch Nelaton catheters. Although commercially available coated single use catheters are popular in hospitals, Nelaton catheters with applied lubricating gel are significantly cheaper in the community. There is a small risk of urethral trauma and subsequent stricture associated with re-usable catheters. However, patients appear no more vulnerable to infection by using such catheters, and in developing countries (provided they can be washed in clean water) re-usable catheters should be the first choice.

The long-term results of ISC compare favourably with other forms of bladder management, and the incidence of infection and stone formation is considerably less than in those patients with long-term indwelling catheters.

Optimum requirements for intermittent self-catheterisation:

- Minimal detrusor activity

- Large capacity bladder

- Adequate outlet resistance

- Manual dexterity

- Pain-free catheterisation

- Patient motivation

Investigations and urological review

Radiology

Ultrasound (US)

This is the most useful non-invasive technique to monitor bladder emptying and the integrity of the upper tracts. The combination of plain abdominal radiography with US has superseded routine intravenous urography for annual review, and most of the important changes to the upper tracts, especially dilatation, parenchymal scarring, and stone formation, can be diagnosed on US. When abnormalities are detected, other imaging modalities may be required.

Video-urodynamics

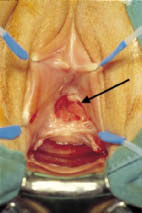

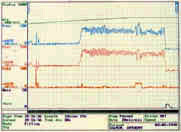

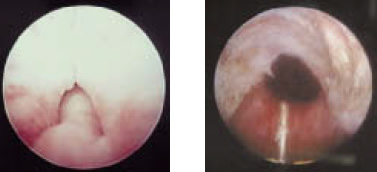

Although the degree of detrusor activity may be predicted by the level of the SCI, formal baseline studies should be performed at 3–4 months to enable definitive bladder management to be planned. The investigation is in two parts. The cystometrogram relates the filling pressure to bladder volumes, and identifies and quantifies unstable contractions and abnormalities of compliance. The simultaneous contrast radiological study allows screening of the bladder and urethra. This is an important part of the investigation and is video-recorded or the images digitised. In many patients with a suprasacral cord lesion, detrusor contractions are associated with a simultaneous contraction of the distal sphincter mechanism — the void is obstructed due to the "dyssynergic" distal sphincter. Dyssynergic high pressure voiding frequently causes autonomic dysreflexia, a potentially serious and occasionally fatal autonomic disturbance resulting in severe hypertension. It is discussed in detail in chapter 6. Although the distal sphincter eventually relaxes, the unstable "voiding" detrusor contraction usually fades away before the bladder has emptied properly, leaving a significant residual. This encourages infection and stone formation, and ongoing unstable contractions often lead to vesico-ureteric reflux, hydronephrosis, and pyelonephritis. The contrast part of the study helps characterise many aspects of these extremely important complications, and enables appropriate (often surgical) action to be taken before irreparable damage takes place.

Effects of detrusor-distal sphincter dyssynergia:

- High bladder pressures → Vesico-ureteric reflux → Hydronephrosis → Chronic renal failure

- Incomplete bladder emptying → Recurrent urinary tract infections → Pyelonephritis → Chronic renal failure

Isotope renography/nuclear medicine

DMSA renography is a sensitive indicator of renal scarring and differential renal function, and is indicated when US studies suggest upper tract damage. DTPA and MAG 3 renography are useful investigations to characterise upper tract obstruction, and also to monitor the progress of the kidney after treatment for vesico-ureteric reflux. Serial estimation of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using Cr-EDTA or Tc-DTPA is a sensitive method of determining any decline in renal function, and a reduction in GFR (or creatinine clearance) is observed before changes can be measured in serum creatinine.

Isotope renography in spinal cord injury:

| DMSA | Tc-DTPA and MAG3 | Cr-EDTA GFR |

- Differential renal function |

- Diagnosis and follow-up of uretero-pelvic junction or ureteral obstruction - Indirect cystography for vesico-ureteric reflux - Differential renal function - Indirect measurement of GFR |

- Serial assay is a sensitive index of small changes in GFR |

Biochemistry

Routine baseline serum creatinine, urea and electrolyte estimations are performed, and should be repeated annually until the clinician in charge is certain that the urinary tract is completely stable on definitive management, and with no significant radiological or urodynamic prognostic risk factors.

Later management

In many patients the early management of the urinary tract merges with the long-term plan. With the increasing use of suprapubic catheters at an initial stage, many tetraplegic patients are discharged into the community content not to alter this method of bladder management. However, both suprapubic and urethral catheters should be discouraged where safer methods are available, especially in paraplegics. Above all, the merits of ISC should be stressed to the patient. In those men whose penis will retain a condom, sheath drainage is an extremely safe method of bladder management. Where necessary, endoscopic distal sphincterotomy is undertaken to abolish dyssynergia.

Personal choice is now emerging as a major factor in planning, and the individual’s lifestyle preferences must be taken account of, though not at the expense of risk to the upper tracts. Some aspire to continence and freedom from indwelling catheters. Others are unwilling to self-catheterise, and will not relinquish their suprapubic catheters. Tetraplegics with poor hand function have fewer choices available to them, and avoidance of autonomic dysreflexia and freedom from infection may be the dominating influences in their personal choice.

After the first year, many paraplegic and a few incomplete tetraplegic patients wish to explore alternatives that allow freedom from permanent catheterisation, and restoration of continence. Patient awareness and lifestyle aspirations are increasing the demand for complex lower urinary tract reconstruction. Surgical options are tailored for each individual, and the urologist advising spinally damaged patients must balance the potential to improve symptoms against unrealistic patient expectations and the possibility of surgical complications.

Simultaneous faecal incontinence and female pelvic floor disorders (especially following cauda eqina lesions) frequently require a multidisciplinary approach. In particular, the involvement of specialist nurse practitioners and stomatherapists at an early stage in planning treatment is emphasised.

Detrusor hyperreflexia

In the presence of DSD, sustained rises in detrusor pressure (Pdet) may result in severe renal damage secondary to obstruction or high pressure vesico-ureteric reflux of (infected) urine. Continence and voiding are secondary considerations in these cases (nearly always males), where renal preservation is of the utmost priority. Recurrent suprapubic catheter blockage is common, even in the absence of calculous debris, and may result from catheter shaft compression by grossly unstable bladder contractions and mucosal plugging. Significant rises in detrusor pressure may occur even in the presence of an indwelling catheter on free drainage, and an association between these unstable contractions and upper tract scarring has recently been confirmed. Suprapubic catheters (SPC) should be cycled on at least two occasions each day, and simultaneous anticholinergic therapy should be used. Some men may opt for distal endoscopic sphincterotomy or stenting and condom drainage rather than SPC. Stents are less reliable in SCI patients than in those with outflow obstruction associated with prostatic enlargement. Others may be obese or suffer penile retraction, and condom sheath drainage may be impossible.

Detrusor hyperreflexia in the presence of DSD — Risks:

- Autonomic dysreflexia in patients with spinal cord lesions above T6

- Renal damage due to obstruction, high pressure vesico-ureteric reflux

The maintenance of continence is of vital importance to personal morale, and for the preservation of intact perineal and buttock skin. We briefly examine some of the many surgical procedures available to restore continence and to facilitate self-catheterisation.

Detrusor hyperreflexia — medical management:

- Anticholinergic treatment: Oxybutynin, Tolterodine, Propiverine HCI, Flavoxate, Propantheline

- Intravesical therapy (experimental): Capsaicin, Resiniferatoxin

Detrusor hyperreflexia — surgical management:

- Augmentation cystoplasty

- Sacral anterior root stimulator (SARS)

- Posterior rhizotomy

- Urinary diversion

Augmentation cystoplasty

Where conventional medical treatment with anticholinergic therapy has failed, and if indwelling catheters are to be avoided, the bladder must be deafferentated or bisected and augmented with a patch of bowel to provide a bladder of sufficient compliance and volume to safely accommodate a socially useful volume of urine. In female patients, DSD is very unusual, and severe incontinence rather than upper tract protection is the main indication for augmentation. After augmentation, inability to void is the rule rather than the exception, and the patient must demonstrate the willingness and ability to self-catheterise before surgery can be contemplated.

Even after augmentation, anticholinergic therapy may be required to make the patient completely dry. Cystitis may be a recurrent problem after enterocystoplasty, and there remains a long-term theoretical risk of neoplastic transformation in the enteric patch, especially if this is colon. Nitrosamine production associated with UTI has been implicated in this process.

For those who cannot access their own urethra (wheelchair-bound females being an especially important group), the simultaneous provision of a self-catheterising abdominal stoma (Mitrofanoff) may be an integral part of the initial surgery (see below).

Neuromodulation and sacral anterior root stimulation (SARS)

In patients with complete suprasacral cord lesions, functional electrical stimulation of the anterior nerve roots of S2, S3 and S4 is very successful in completely emptying the paralysed bladder. Assisted defaecation, and in the male, implant-induced erections may be coincidental advantages of the implant. The device most commonly in use is the Finetech-Brindley stimulator; the anterior roots of S2, S3 and S4 are stimulated via a receiver block implanted under the skin, and a posterior rhizotomy is performed simultaneously. This cures reflex incontinence, improves bladder compliance and diminishes DSD, and thus ensures that neither the use of the implant nor overfilling of the bladder will trigger autonomic dysreflexia. Reflex erections and ejaculation will be lost with posterior rhizotomy, and simultaneous neuromodulation is under investigation as an alternative to rhizotomy in men.

No comparative or controlled prospective studies between augmentation cystoplasty and SARS are yet available, but despite its cost, the stimulator is amongst the first in a line of options designed to keep this group of patients catheter free.

Stress incontinence

Both male and female patients with conus and cauda equina lesions are vulnerable to sphincter weakness incontinence (SWI), as well as older women with pre-existing pelvic floor disorders, prolapse, etc. regardless of the neurological level of injury. This often manifests itself later as the patient becomes more active during rehabilitation, urinary leakage occurring for example on transfer to and from the wheelchair.

Colposuspension, pubo-urethral slings and, recently, tension free vaginal tapes are effective in treating SWI, though sometimes obstructive in patients with acontractile bladders attempting to void by straining or compression. In paraplegic females, urethral closure and SPC is a reliable method of ensuring continence, though where appropriate, permanent suprapubic catheterisation may be avoided by performing a Mitrofanoff procedure. Bladder neck injections with bulking agents have a less reliable record in this difficult group.

Artificial urinary sphincters (AUS) have an excellent record of continence, but there is a higher attrition rate in paraplegics due to infection or cuff erosion, especially if ISC is undertaken regularly. Placement around the bulbar urethra should be avoided in patients confined to a wheelchair, and impotence frequently complicates cuff placement in the membranous position. For both male and female paraplegic patients the bladder neck is therefore the optimal site for AUS cuff placement.

The acontractile bladder and assisted voiding

Since the adoption and widespread use of intermittent self-catheterisation (ISC) in detrusor failure the complications of chronic retention and long-term catheterisation have been significantly reduced. Most patients with good hand function manage the technique, though paraplegic females have more difficulty accessing their urethra. This may be sufficient to cause them to abandon attempts in favour of long-term suprapubic catheterisation.

Since Mitrofanoff first described his technique in children, the procedure has been adapted to other circumstances, including stomal intermittent self-catheterisation in the paraplegic wheelchair-bound female patient. Even in tetraplegic patients with limited hand function stomal ISC is sometimes feasible with careful siting of the channel. In those patients who have undergone a Mitrofanoff procedure, stomal ISC is usually regarded as preferable to urethral catheterisation, and females whose native urethra remains in situ and who have a stoma almost never catheterise their own urethra. Complications of the procedure are irritatingly frequent though rarely life-threatening. Minor "plastic" procedures for stomal stenosis are required in up to 30% of cases and complete channel revisions for leakage or failure are necessary in 15%.

The procedure may be undertaken in conjunction with bladder augmentation and/or bladder neck closure for intractable incontinence.

Mixed faecal and urinary incontinence

Cauda equina lesions causing sphincter weakness frequently result in mixed faecal and urinary incontinence. This may have a devastating impact on rehabilitation, and the urologist should not consider involuntary urinary loss in isolation. Malone described the effectiveness of the antegrade colonic (continence) enema (ACE) in children with meningomyelocoele, and it may be helpful in managing sphincter weakness faecal incontinence secondary to cauda equina or conus injury. The procedure (like the Mitrofanoff) consists of the construction of a self-catheterising channel from appendix or tapered small bowel between abdominal wall and underlying caecum or colon. Every 48 hours or thereabouts, the bowel is intubated via the stoma, and a large volume enema (e.g. 2 L water) administered to wash the bowel clear of faeces. Continence is achieved until the large bowel refills. The ACE procedure is much less effective in treating the profound constipation frequently encountered in suprasacral SCI. The procedure can be performed simultaneous to a Mitrofanoff, colposuspension, urethral closure, or bladder neck cuff implantation, although the remaining components of the AUS should not be implanted due to the risk of infection.

See also

- At the accident:

- History and epidemiology of spinal cord injury

- Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

- Evacuation and initial management at hospital:

- Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Initial management of patients with spinal cord injuries at the receiving hospital

- Neurological assessment of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Spinal shock after severe spinal cord injury

- Partial spinal cord injury syndromes

- Radiological investigations:

- Initial radiography of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Cervical injuries

- Thoracic and lumbar injuries

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — I:

- Respiratory complications

- Cardiovascular complications

- Prophylaxis against thromboembolism

- Initial bladder management

- The gastrointestinal tract

- Use of steroids and antibiotics

- The skin and pressure areas

- Care of the joints and limbs

- Later analgesia

- Trauma re-evaluation

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — II:

- The anatomy of spinal cord injury

- The spinal injury (cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine)

- Transfer to a spinal injuries unit

- Medical management in the spinal injuries unit:

- The cervical spine injuries

- The cervicothoracic junction injuries

- Thoracic injuries

- Thoracolumbar and lumbar injuries

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Biochemical disturbances

- Para-articular heterotopic ossification

- Spasticity

- Contractures

- Pressure sores

- Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury:

- Nursing for people with spinal cord lesion:

- Physiotherapy after spinal cord injury:

- Respiratory management

- Mobilisation into a wheelchair

- Rehabilitation

- Recreation

- Incomplete lesions

- Children

- Occupational therapy after spinal cord injury:

- Hand and upper limb management

- Home resettlement

- Activities of daily living

- Communication

- Mobility

- Leisure

- Work

- Social needs of patient and family:

- Transfer of care from hospital to community:

- Education of patients

- Teaching the family and community staff

- Preparation for discharge from hospital

- Easing transfer from hospital to community

- Travel and holidays

- Follow-up

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — I:

- Late spinal instability and spinal deformity

- Pathological fractures

- Post-traumatic syringomyelia (syrinx, cystic myelopathy)

- Pain

- Sexual function

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — II:

- Later respiratory management of high tetraplegia

- Psychological factors

- The hand in tetraplegia

- Functional electrical stimulation

- Ageing with spinal cord injury

- Prognosis

- Spinal cord injury in the developing world: