Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

In the absence of an immediate threat to life such as fire, collapsing masonry, or cardiac arrest, casualties at risk of spinal injury should be positioned on a spinal board or immobiliser before they are moved from the position in which they were initially found. Immobilisers are short backboards that can be applied to a patient sitting in a car seat whilst the head and neck are supported in the neutral position. In some cases the roof of the vehicle is removed or the back seat is lowered to allow a full-length spinal board to be slid under the patient from the rear of the vehicle. A long board can also be inserted obliquely under the patient through an open car door, but this requires coordination and training as the casualty has to be carefully rotated on the board without twisting the spine, and then be laid back into the supine position. Spinal immobilisers do not effectively splint the pelvis or lumbar spine but they can be left in place whilst the patient is transferred to a long board.

Both short and long back splints must be used in conjunction with a semirigid collar of appropriate size to prevent movement of the upper spine. If the correct collars or splints are not available manual immobilisation of the head is the safest option. Small children can be splinted to a child seat with good effect—padding is placed as necessary between the head and the side cushions and forehead strapping can then be applied.

If lying free, the casualty should ideally be turned by four people: one responsible for the head and neck, one for the shoulders and chest, one for the hips and abdomen, and one for the legs. The person holding the head and neck directs movement. This team can work together to align the spine in a neutral position and then perform a log roll allowing a spinal board to be placed under the patient. Alternatively the patient can be transferred to a spinal board using a “scoop” stretcher which can be carefully slotted together around the casualty.

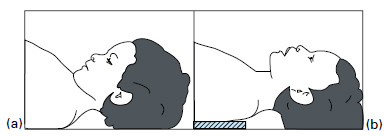

In the flexion-extension axis, the neutral position of the cervical spine varies with the age of the patient. The relatively large head and prominent occiput of small children (less than 8 years of age) pushes their neck into flexion when they lie on a flat surface. This is corrected on paediatric spinal boards by thoracic padding, which elevates the back and restores neutral curvature. Conversely, elderly patients may have a thoracic kyphosis and for this a pillow needs to be inserted between the occiput and the adult spinal board if the head is not to fall back into hyperextension. In all instances, the aim is to achieve normal cervical curvature for the individual. For example, extension should not be enforced on a patient with fixed cervical flexion attributable to ankylosing spondylitis.

A small child may not tolerate a backboard. One alternative is a vacuum splint (adult lower limb size) which can be wrapped around the child like a vacuum mattress (see below). However, an uncooperative or distressed child might have to be carried by a paramedic or parent in as neutral a position as possible, and be comforted en route.

For transportation, the patient should be supine if conscious or intubated. In the unconscious patient whose airway cannot be protected, the lateral or head-down positions are safer and these can be achieved by tilting or turning the patient who must be strapped to the spinal board. To stabilise the neck on the spinal board, the semirigid collar must be supplemented with sandbags or bolsters taped to the forehead and collar. Only the physically uncooperative or thrashing patient is exempt from full splintage of the head and neck as this patient may manipulate the cervical spine from below if the head and neck are fixed in position. In this circumstance, the patient should be fitted with a semirigid collar only and be encouraged to lie still. Such uncooperative behaviour should not be attributed automatically to alcohol, as hypoxia and shock may be responsible and must be treated.

If no spinal board is used and the airway is unprotected, the modified lateral position (Figure 1.3(b)) is recommended with the spine neutral and the body held in position by a rescuer. In the absence of life-threatening injury, patients with spinal injury should be transported smoothly by ambulance, for reasons of comfort as well as to avoid further trauma to the spinal cord. They should be taken to the nearest major emergency department but must be repeatedly assessed en route; in particular, vital functions must be monitored. In transit the head and neck must be maintained in the neutral position at all times. If an unintubated supine trauma patient starts to vomit, it is safer to tip the casualty head down and apply oropharyngeal suction than to attempt an uncoordinated turn into the lateral position. However, patients can be turned safely and rapidly by a single rescuer when strapped to a spinal board and that is one of the advantages of this device.

Hard objects should be removed from patients’ pockets during transit, and anaesthetic areas should be protected to prevent pressure sores.

The usual vasomotor responses to changes of temperature are impaired in tetraplegia and high paraplegia because the sympathetic system is paralysed. The patient is therefore poikilothermic, and hypothermia is a particular risk when these patients are transported during the winter months. A warm environment, blankets, and thermal reflector sheets help to maintain body temperature.

When the patient has been injured in an inaccessible location or has to be evacuated over a long distance, transfer by helicopter has been shown to reduce mortality and morbidity. If a helicopter is used, the possibility of immediate transfer to a regional spinal injuries unit with acute support facilities should be considered after discussion with that unit.

See also

- At the accident:

- History and epidemiology of spinal cord injury

- Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

- Evacuation and initial management at hospital:

- Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Initial management of patients with spinal cord injuries at the receiving hospital

- Neurological assessment of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Spinal shock after severe spinal cord injury

- Partial spinal cord injury syndromes

- Radiological investigations:

- Initial radiography of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Cervical injuries

- Thoracic and lumbar injuries

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — I:

- Respiratory complications

- Cardiovascular complications

- Prophylaxis against thromboembolism

- Initial bladder management

- The gastrointestinal tract

- Use of steroids and antibiotics

- The skin and pressure areas

- Care of the joints and limbs

- Later analgesia

- Trauma re-evaluation

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — II:

- The anatomy of spinal cord injury

- The spinal injury (cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine)

- Transfer to a spinal injuries unit

- Medical management in the spinal injuries unit:

- The cervical spine injuries

- The cervicothoracic junction injuries

- Thoracic injuries

- Thoracolumbar and lumbar injuries

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Biochemical disturbances

- Para-articular heterotopic ossification

- Spasticity

- Contractures

- Pressure sores

- Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury:

- Nursing for people with spinal cord lesion:

- Physiotherapy after spinal cord injury:

- Respiratory management

- Mobilisation into a wheelchair

- Rehabilitation

- Recreation

- Incomplete lesions

- Children

- Occupational therapy after spinal cord injury:

- Hand and upper limb management

- Home resettlement

- Activities of daily living

- Communication

- Mobility

- Leisure

- Work

- Social needs of patient and family:

- Transfer of care from hospital to community:

- Education of patients

- Teaching the family and community staff

- Preparation for discharge from hospital

- Easing transfer from hospital to community

- Travel and holidays

- Follow-up

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — I:

- Late spinal instability and spinal deformity

- Pathological fractures

- Post-traumatic syringomyelia (syrinx, cystic myelopathy)

- Pain

- Sexual function

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — II:

- Later respiratory management of high tetraplegia

- Psychological factors

- The hand in tetraplegia

- Functional electrical stimulation

- Ageing with spinal cord injury

- Prognosis

- Spinal cord injury in the developing world: