Nursing for people with spinal cord lesion

The main nursing objectives in providing care for people who have sustained a spinal cord lesion are to: identify problems and prevent deterioration; prevent secondary complications; facilitate maximal functional recovery; support patients and significant others in learning to adjust to the patients’ changed physical status; be aware of the effect of the injury on the patients’ perception of self worth; give high priority to empowering patients, enabling them to take control of their life through formal and informal education.

Nurses need to recognise that patients will spend a long time in hospital, probably between four and nine months. Most patients are male (4 : 1 men to women) aged between 15 and 40 years, but an increasing number of older people are sustaining injuries. Patients will initially be very dependent on others, and those with high lesions or from the older age group may continue to be dependent and have a disappointing level of neurological recovery and functional outcome.

Nursing aims:

- Identify problems and prevent deterioration

- Prevent secondary complications

- Maximise functional recovery

- Support patients and relatives

- Empower patients

- Educate patients to take control of their lives

Factors which contribute to establishing close and supportive relationships between staff and patients often blur boundaries between professional and personal roles. This, with the psychological support required by patients, and the increased need for physical input, offers many challenges, yet many rewards to the nurse involved in care.

Psychological trauma:

- Fear and anxiety

- Sensory deprivation

- Wide variety of moods

- Behaviour similar to the grieving process

The psychological trauma of spinal cord injury is profound and prolonged. The impact on the injured person and his or her family is highly individual and varies from patient to patient throughout the course of their care. Fear and anxiety, worsened by sensory deprivation, may initially be considerable and continue in some degree for many months. During the acute phase, particularly when patients are confined to bed, they may experience a wide variety of mood swings including anger, depression, and euphoria. They may exhibit behaviour identifiable with a normal grieving process — guilt, denial or other coping mechanisms such as regression. They may suffer from a sense of frustration, be verbally demanding, or sometimes withdrawn.

Relatives often progress to adjustment much more quickly than the patients themselves, and this may complicate planning for the future. Intervention must take into consideration the coping mechanisms used by the patients and their families. Long-term decisions must not be taken before patients are willing and able to participate.

Stressful rehabilitation landmarks:

- Any occasion experienced for the first time

- Visits home to family and friends

- Discharge

Certain landmarks in rehabilitation are especially stressful for the patient. Any occasion experienced for the first time after injury is likely to be psychologically demanding. Being mobilised from bed to wheelchair is one example, with its combination of blood pressure instability, physical exhaustion, and the shock of coming to terms with altered body sensation and image. For many, visits to home and friends are other physical and psychological hurdles that must be crossed. Most spinal injuries units have an "aid to daily living" (ADL) flat, where patients and their carer can stay prior to their first weekend at home, with staff close at hand if problems arise.

These events need careful preparation, with discussion taking place before and afterwards, initially with staff from the unit, and later with family and friends. Discharge from hospital is a considerable challenge, with patients and their families often having to cope with lack of stamina; loneliness; social isolation, and the changed relationship caused by injury. Continuing support will be needed for at least two to three years while the patient adjusts to his or her new lifestyle.

Nursing management

In the emergency department

Many patients arrive in the emergency department from the scene of an accident on a spinal board, which enables the paramedics to immobilise the back or neck, and maintain spinal alignment. If a cervical spine injury is suspected, and no collar has been applied, the neck should be immobilised by using a semirigid collar supplemented with sandbags or bolsters taped to the forehead and collar, except in the case of the physically uncooperative or thrashing patient (see chapter 2). In an ideal situation, the collar must remain in place until completion of the initial assessment, resuscitation, and diagnostic x rays. The decision to remove the collar must be made by a competent member of the medical team.

Emergency management:

- Immobilisation of the neck

- Co-ordinated team

- Remove from spinal board

- Remove clothing

- Examine skin for marking and damage

- Pressure relief

The non-conforming nature of the spinal board means that potential pressure points are exposed to high interface pressures. This necessitates removal of the spinal board as soon as is appropriate by a coordinated trained team. With the neck held, and with the use of a log roll, the patient should be transferred using a sliding board on to a well-padded trauma trolley with a firm base, in case resuscitation is needed. If resuscitation or the insertion of an airway is necessary, the chin lift or jaw thrust manoeuvre and not a head tilt is used for unconscious patients and those with suspected cervical spine lesions.

Hypothermia. High lesion patients are poikilothermic, therefore risk of hypothermia, with:

- Confusion

- Bradycardia → cardiac arrhythmias

- Hypoventilation

- Hypotension

All clothing should be removed to facilitate full examination and inspection for skin damage. Care should be taken not to raise both of the arms above head level, to reduce the risk of cord lesion extension. Upper thoracic and cervical cord lesion patients may become poikilothermic (taking on the surrounding environmental temperature), with a tendency towards hypothermia. During the assessment phase, and their time in the emergency department, care must be taken to maintain the patient’s temperature within acceptable levels.

![]() Attention! Patient centred interdisciplinary approach - Essential throughout all stages of rehabilitation.

Attention! Patient centred interdisciplinary approach - Essential throughout all stages of rehabilitation.

Once a spinal cord injury has been diagnosed, care of pressure areas is extremely important. If delay in admission to the ward, where the patient will be nursed on a pressure-relieving mattress, is expected, the patient must be log rolled into the lateral position for one minute every hour. A firm mattress is more supportive to the spine, and far more comfortable.

In the acute and rehabilitation care setting

A patient-centred approach is essential to meet the various problems with which a patient may present. In the initial acute phase, nursing care will be implemented to meet the patient’s own inability to maintain his or her own activities of daily living. As the patient progresses through the rehabilitation phase, the nurse’s role becomes more supportive and educative, with the patient taking responsibility through self-care or by directing carers.

Choice of bed

The standard King’s Fund bed, or profiling bed, with a stable mattress consisting of layers of varying density foam, is suitable for most patients, with the addition of a Balkan beam and spreader bar. It is probably the best bed for tetraplegics requiring skull traction, facilitating good positioning of the shoulders and arms. An electrically powered turning and tilting bed is particularly suitable for heavy patients, and those with multiple injuries. It facilitates postural drainage in chest injuries. It permits easier nursing as far as numbers are concerned, but still requires a full team of five or four nurses for inspection of pressure points, especially the natal cleft, for hygiene requirements, and bowel management.

Positioning

Regular position changing is every two to three hours initially to relieve pressure. Skin inspection for red marks, spinal alignment and positioning of limbs is essential for a patient with spinal cord injury. The aims are simple: to support the injured spine in a good healing position; to maintain limbs and joints in a functional position, thus avoiding deformity and contractures, and to reduce the incidence of spasticity. There are several ways of achieving these aims, so the methods chosen should follow discussion with the interdisciplinary team, and suit the patient, level of injury, and the availability, knowledge and skill of the nursing staff.

Acute phase:

- Support injured spine in alignment

- Maintain limbs and joints in functional position

- Passive movements

Spinal alignment

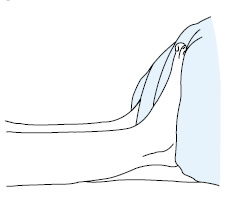

Before undertaking a turn or preparing to move/transfer a patient, spinal alignment should be maintained by checking (when the patient is supine) that the nose, sternum and symphysis pubis are in alignment and that the shoulders and hips are level. A shoulder hold provides countertraction by applying pressure onto the shoulders to prevent an upward movement.

Handling and turning

Patient handling techniques need to be considered in relation to the Manual Handling Operations Regulations 1992. Patients with spinal cord injury are unable to help, and care must be taken to maintain alignment and stability of the neck and back at all times throughout the handling technique. This may pose problems for the staff when considering the method of transfer and movement of a patient, hence the need for rigorous assessment with the application of ergonomic principles.

Manual hoisting aids with stretcher attachments, and side to side, and up and down transfer products are available in the United Kingdom. Outside the European Community, and especially in developing countries, handling equipment may not be available, and there may be no alternatives following risk assessment but to handle the patient manually.

When transferring or moving a patient with an acute cervical injury, to maintain neck alignment and stability, the "lead" nurse holds the neck and head with both hands under the neck, and both wrists supporting the patient’s head behind the ears. The nurse at the patient’s head takes control and coordinates the turn after checking her team is ready.

Countertraction, starting at the top of the patient, may also be used to prevent movement of the spine when inserting hands or equipment under the patient, or starting at the foot end first when hands are being withdrawn.

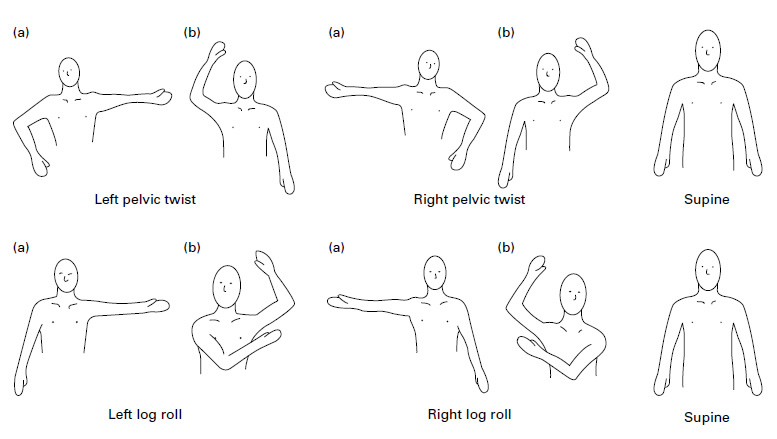

A log roll is needed for carrying out nursing care, such as bowel management, skin hygiene, and for lateral positioning of both paraplegic and tetraplegic patients. Figure shows how the paraplegic patient should be held when preparing to turn. Note the injury site is well supported. When the log roll is complete, the patient remains supported by pillows. Note the alignment of the shoulders, hip, iliac crest, and upper leg in figure. A tetraplegic patient will require a head hold to complete this move. The nurse performing the head hold coordinates the manoeuvre. End positioning of the head will be determined by the mechanism of injury and the head and neck will be maintained in a neutral, extended, or flexed position, using a "water bag", neck roll, sand bag, or pillows.

The pelvic twist

The pelvic twist is a simple turn needing only three nurses to perform and suitable for many tetraplegic patients. It must not be used for patients with thoracolumbar lesions. The nurse at the patient’s head holds the shoulders securely to the bed; the second nurse (standing on the side to which the patient is being turned), applies countertraction and gets ready to support the back and legs on completion of the twist, before inserting the pillows. The third nurse proceeds with the twist by placing her or his upper arm under the patient’s back (using countertraction), and her or his lower arm under the patient’s nearest thigh, and over the furthest thigh to support and move the hip. The movement is a gentle lift and turn of the near hip joint, enough to free the sacrum of any pressure. On completion of the turn, a pillow is folded in half into the lumbar region to support the back and pelvis, and two pillows are placed under the upper leg.

In all turns involving tetraplegic patients, the nurse holding the head is in charge of the timing and coordination of the team. The frequency of turns in the acute stage of management is determined by the patient’s tolerance, but length between turns should not be greater than three hours.

Once the patient has progressed into the rehabilitation phase of care, the interval between turns can be increased, as long as there is no skin marking. The number of pillows used to support the body and limbs may be decreased.

Legs

When patients are supine, avoid hyperextension of the knees. Keep the feet in line with the hips and hold the feet at 90° using a foot board and pillows. Avoid pressure on the heels.

When patients are on their side, the lower leg should be extended, with the upper leg slightly flexed and resting on pillows, and not over the lower leg.

Arms

When tetraplegic patients are supine, between turns, their joints need to be placed gently through a full range of positions to prevent stiffness and contractures. Hands and arms must always be supported through the movement. If remaining in the supine position, arms and hands need to be supported down by the patient’s side.

When positioning the patient in a left or right pelvic twist, the arm facing the same direction as the twist can either be extended straight out (a), or the forearm placed pointing towards the head or downwards towards the feet (b). The forearm on the side away from the twist should point to the head or feet, but should not be in a similar position to the other arm (b).

In log rolls the lower arm is extended (a), with the upper arm placed at the patient’s side, or flexed across the chest (b).

The arm positions (a) or (b) are changed as the patient is rotated through a turning regime of, for example: Pelvic twist: left pelvic twist → right pelvic twist → supine.

or Log roll: log roll to the left → log roll to the right → supine. The turning regime will depend on the skin condition and comfort of the patient.

The shoulders and arms should always be protected from pressure — by gentle handling and good support with pillows.

Nursing intervention

Internal environment

Patients with high thoracic and cervical lesions are susceptible to respiratory complications, and a health education programme should be implemented with the long-term goal of reducing the risk of chest infections.

Monitoring in the acute phase should include skin colour, level of orientation, respiratory rate and depth, chest wall and diaphragmatic movement, oxygen saturation, chest auscultation, and vital capacity. Some patients will require additional oxygen therapy and possibly non-invasive pressure support. A physiotherapy programme will need to be continued throughout the 24-hour period with assisted coughing and bronchial and oral hygiene.

Maintaining internal environment:

- Respiration/support

- Assisted coughing

- Bronchial and oral hygiene

- Cardiovascular monitoring

- Antiembolism stockings

- Temperature control

Cardiovascular monitoring will include not only the patient’s blood pressure and pulse (high lesion patients may be hypotensive and bradycardic), but also observing for evidence of deep vein thrombosis. As well as measuring the circumference of the calves and thighs, the patient’s temperature must be monitored, as a low grade pyrexia is sometimes the only indication that thromboembolic complications are developing. Appropriately measured and fitted thigh-length antiembolism stockings should be applied.

The patient’s body temperature should be maintained — high lesion patients are poikilothermic, and therefore hypothermia is a risk, particularly in cold weather.

Profound loss of sensation below the level of the lesion, a restricted visual field due to enforced bed rest, unfamiliar surroundings and many interruptions imposed on newly injured patients in the early stages may cause sensory deprivation leading to confusion and disorientation.

Sensory deprivation:

- Familiarisation of environment

- Interpretation of incoming stimuli

- Higher levels of cognitive functioning

- Reality orientation

- Decision-making role

The imbalance can be redressed by increasing sensory input to the patient, but at the same time being careful not to overload the patient. Many tools can be used, one of which is that of touch, in a caring comforting manner, above the level of the lesion. Mirrors can be placed strategically to extend the field of vision and reality training employed by using clocks, calendars, newspapers, by using friends and relatives, and most importantly by allowing the patient to have a decision-making role.

Pain management

Pain management in the spinal cord injured patient is complex because of the various factors that can contribute towards the pain, both physical and emotional. Despite their paralysis, patients can still experience pain at the injury site. The use of a continuous infusion of opioids, normally subcutaneous, backed by the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs usually provides satisfactory relief. Careful monitoring, including pulse oximetry, is necessary whilst the infusion is in use. Some patients develop shoulder pain, which needs to be managed with both physiotherapy and analgesia.

Pain management:

- Continuous infusion

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Skin hygiene and care

Skin cleanliness is fundamental, and good long-term arrangements for bathing or showering must be made. Minor skin infections should be treated and toe nails cut short and straight across, as ingrowing toe nails are particularly common. From an early stage, patients must be taught about the hazards of sensory loss and the need to inspect their skin and extremities regularly. They must be conscious of the effects of pressure and appreciate that the risk of pressure sores increases during times of emotional distress, tiredness, depression, and intercurrent illness.

Education is also important to enable the patient to select suitable clothing, with sore prevention and poikilothermia in mind.

Skin care:

- Avoid damage

- Educate regarding risks

- Examine and relieve pressure regularly

- Select suitable clothing

- Keep clean

- Treat minor abrasions/injuries

Nutrition

Life-threatening conditions in the initial phase often overshadow the nutritional needs of the patient. The risk factors associated with trauma, the initial period of paralytic ileus, a reduced oral intake, anorexia and the inability to use the hands in high lesions, can all lead to malnutrition, skin complications, and severe weight loss. The nursing goal in the acute phase is to maintain nutritional support by: performing a nutritional risk assessment with the dietitian; implementing parenteral or enteral feeding when necessary; and encouraging and helping to feed the patient with their diet and nutritional supplements.

In the rehabilitation phase, the nurse needs to be familiar with feeding aids provided by the occupational therapist and to implement an individual education programme.

Nutrition:

- Nil by mouth initially

- Nutritional risk assessment

- Parenteral/enteral feeding

- Education - diet, feeding aids

Bladder management

During the acute phase of spinal cord injury, bladder management involves strict fluid monitoring and insertion of an indwelling urethral or suprapubic catheter with, initially, hourly urine measurements.

The sudden hypotension in high lesions, and the large amounts of antidiuretic hormone secreted by the pituitary as a response to the stress of a major injury, leads to oliguria followed in some cases by a marked post-traumatic diuresis. It is important to prevent overdistention of the bladder during this stage, which could otherwise lead to overstretching of nerve endings and muscle fibres, inhibiting their potential to recover, which in turn could reduce the long-term management options for the patient.

Bladder management – acute phase:

- Strict fluid monitoring

- Avoidance of overdistension of bladder

- Strict asepsis and good hygiene

The prevention of urinary tract infection through the implementation of good hygiene, adequate fluid intake and strict asepsis is vital.

The long-term aim is the prevention of complications such as urinary tract infections and calculi, as they may hinder a successful rehabilitation programme. Support and education by skilled staff enables the patient to make an informed choice as to the method of bladder management best suited to him/her, which in turn should improve the quality of life.

Bladder management – long term aims:

- Preservation of renal function

- Continence

- Prevention of infection, calculi and urethral trauma

- Appropriate fluid intake

- Informed choice of suitable bladder management program

- Individual education package

Catheterisation, either by the patient or carer, requires careful preparation and teaching, to provide the physical and psychological support necessary. Coming to terms with loss of this bodily function is often one of the hardest outcomes of SCI that the patient has to accept. Female patients provide an even greater challenge in the achievement of continence, because of "hormonal" leaking during the premenstrual and menstrual period, or a previous history of stress incontinence.

Long-term suprapubic catheterisation is now a popular method of management. It is sexually and aesthetically more acceptable, as well as reducing the risk of urethral damage associated with long-term urethral catheterisation. Patients and carers are taught to change their suprapubic catheters.

However, the use of long term indwelling catheters, either urethral or suprapubic, should not be generally recommended, because of the high incidence of side effects, including calculus formation and urinary tract infection. The presence of an indwelling catheter does not prevent upper urinary tract complications.

The temporary use of a suprapubic catheter with a catheter valve is an alternative to intermittent self-catheterisation as a method of training the bladder to empty reflexly.

If possible and practicable, intermittent self-catheterisation is considered one of the best methods of management. Careful control of fluids and a daily routine will be needed to maintain a dry state between catheters.

Emptying the bladder by tapping and expression, using condom sheath drainage, is also an excellent method in appropriate patients.

Part of the education is assisting the patient to adapt their chosen method into their individual lifestyle, as well as teaching the patient what to do if complications such as autonomic dysreflexia arise.

Bowel care

During the period of spinal shock, the bowel is flaccid, so it must not be allowed to overdistend, causing constipation with overflow incontinence. An initial rectal check is made to ascertain whether faeces are present; if they are, they should be manually evacuated. Manual evacuation thereafter will continue daily or on alternate days. Very little bowel activity will be expected for the first two or three days. Evacuation should be performed using plenty of lubricant, and with only one gloved finger inserted into the anus. Trauma, including anal stretching and a split natal cleft, is possible if insufficient care is taken. Suppositories to lubricate or stimulate, possibly with the use of aperients, may be required to achieve an evacuation after the initial period of spinal shock. The patient is taught to have an adequate fibre diet, and a high fluid intake to help prevent constipation. The use of aperients is kept to a minimum, especially in a patient with reflex bowel activity. The use of natural laxatives is encouraged in the diet.

Bowel management:

| Upper motor neurone lesion | Lower motor neurone lesion | Education |

| - Reflex emptying — after suppositories or digital stimulation - May not need aperients if diet appropriate |

- Flaccid - Manual evacuation and aperients usually required but may be able to empty, using abdominal muscles - Suppositories ineffective |

- Program established to meet patient’s lifestyle |

Slowly a routine is established that will fit into the patient’s future lifestyle. Bowel management may be performed daily, or on alternate days, depending upon the individual’s bowel pattern. The patient is encouraged to sit on a specially padded shower chair, so that bowel care can be performed over the toilet, followed by a shower. Sometimes this is not possible due to poor balance or preferred choice, and bowel management continues on the patient’s bed.

Bowel management assessment. Consider:

- Level of injury

- Pre-injury bowel pattern

- Diet/fluid intake

- What previously helped defaecation

- Hand function

- Balance/brace

- Psychological state

Where possible, to promote independent care patients are taught manual evacuation if the bowel is flaccid, or suppositories are inserted and/or digital stimulation performed if they have a reflex bowel. If the patient is unable to carry out this activity, carers or district nurses are taught.

Aims of bowel management:

- Achieve regular bowel emptying by production of a formed stool at a chosen time and place

- Avoid leaks or unplanned emptying

- Avoid constipation and other complications

- Try to complete bowel care in 30–60 minutes

- Be as practical as possible

Sexuality

Following a spinal cord injury patients need to redefine sexuality and all that it encompasses. Nurses have to recognise when patients are ready to discuss sexuality, and respond appropriately as this need is not always verbalised in the early stages, and often manifests itself only in indirect questions or sexual innuendo. Discussion should be encouraged and should include dispelling myths, exploring the patient’s new sexual status, looking at alternative methods, identifying practical problems; and advising on how to deal with them. Referral to medical staff, sexual health specialists and other agencies for further information and management, should be offered as appropriate.

Sexuality:

- Acknowledge the need to discuss sexuality

- Redefine sexuality

- Dispel myths

- Explore opportunity and alternatives

- Advice to overcome practical difficulties

See also

- At the accident:

- History and epidemiology of spinal cord injury

- Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

- Evacuation and initial management at hospital:

- Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Initial management of patients with spinal cord injuries at the receiving hospital

- Neurological assessment of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Spinal shock after severe spinal cord injury

- Partial spinal cord injury syndromes

- Radiological investigations:

- Initial radiography of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Cervical injuries

- Thoracic and lumbar injuries

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — I:

- Respiratory complications

- Cardiovascular complications

- Prophylaxis against thromboembolism

- Initial bladder management

- The gastrointestinal tract

- Use of steroids and antibiotics

- The skin and pressure areas

- Care of the joints and limbs

- Later analgesia

- Trauma re-evaluation

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — II:

- The anatomy of spinal cord injury

- The spinal injury (cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine)

- Transfer to a spinal injuries unit

- Medical management in the spinal injuries unit:

- The cervical spine injuries

- The cervicothoracic junction injuries

- Thoracic injuries

- Thoracolumbar and lumbar injuries

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Biochemical disturbances

- Para-articular heterotopic ossification

- Spasticity

- Contractures

- Pressure sores

- Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury:

- Nursing for people with spinal cord lesion:

- Physiotherapy after spinal cord injury:

- Respiratory management

- Mobilisation into a wheelchair

- Rehabilitation

- Recreation

- Incomplete lesions

- Children

- Occupational therapy after spinal cord injury:

- Hand and upper limb management

- Home resettlement

- Activities of daily living

- Communication

- Mobility

- Leisure

- Work

- Social needs of patient and family:

- Transfer of care from hospital to community:

- Education of patients

- Teaching the family and community staff

- Preparation for discharge from hospital

- Easing transfer from hospital to community

- Travel and holidays

- Follow-up

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — I:

- Late spinal instability and spinal deformity

- Pathological fractures

- Post-traumatic syringomyelia (syrinx, cystic myelopathy)

- Pain

- Sexual function

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — II:

- Later respiratory management of high tetraplegia

- Psychological factors

- The hand in tetraplegia

- Functional electrical stimulation

- Ageing with spinal cord injury

- Prognosis

- Spinal cord injury in the developing world: