Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — I

Late spinal instability and spinal deformity

Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of late spinal instability in patients who have sustained spinal trauma. Pain, increasing deformity and, less frequently, the appearance of a new neurological deficit, are the usual manifestations.

Preventing spinal deformity is extremely important, particularly as correcting an established deformity may be difficult and potentially hazardous if major surgery is necessary. It is therefore important to diagnose and treat spinal instability at an early stage. Patients who have sustained flexion or flexion-distraction injuries to the spine are most at risk of spinal instability, due to the high incidence of posterior spinal column and ligamentous damage. The most important factors contributing to missed instability are the presence of multiple injuries, in particular head injury, the occurrence of spinal injuries at more than one level, and spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality (SCIWORA) which can represent a ligamentous injury.

Predisposing factors:

- Nature of original bony injury

- Age at injury

- Level of lesion

- Completeness of lesion

- Inadequate treatment of bony injury

- Laminectomy without stabilisation and fusion

- Gross leg deformities

The most important factors predisposing to spinal deformity are the nature of the original bony or ligamentous injury, age at injury and the level and completeness of the cord lesion. The growing child is most at risk of developing a major spinal deformity, usually a scoliosis. The higher the neurological level and the more complete the lesion, the greater the tendency to spinal deformity.

Spinal deformity may:

- Predispose to pressure sores due to pelvic obliquity and excessive lumbar lordosis

- Result in decreased lung compliance and potential respiratory embarrassment

Inadequate early treatment of the bony injury or inappropriate surgical exploration by laminectomy without stabilisation and fusion may also lead to late deformity. Inadequate postural management, particularly in seating, with muscle imbalance, may lead to an excessive lumbar lordosis with an anterior pelvic tilt. Conversely a severe lumbar kyphosis with the patient sitting on the sacrum is often associated with the development of a long paralytic scoliosis. Lower limb deformities may also affect the spine — for instance, flexion contractures of the hips cause pelvic obliquity and excessive lumbar lordosis, and if the deformity is asymmetrical scoliosis will result. An optimum posture will reduce the risk of pressure sores.

Prime objective of management of spinal deformity is to prevent progression by:

- Seating and positioning

- Correction of posture

- Bracing

- Surgery in selected cases

In children spinal bracing is required until vertebral growth is completed, and until then periods of sitting should be limited. An erect frame such as a swivel walker and a prone trolley to limit sitting in a wheelchair are helpful, particularly in the very young. In adults with thoracolumbar injury bracing is often advisable even if internal fixation has been performed. High thoracic spinal deformity severe enough to require surgical correction requires careful preoperative assessment, respiratory complications being a particular hazard of the operation.

In patients with incomplete neurological lesions and a severe deformity, the risk of developing a secondary myelopathy if treated conservatively has to be weighed against the considerable risk of major surgery, requiring a combined anterior and posterior approach.

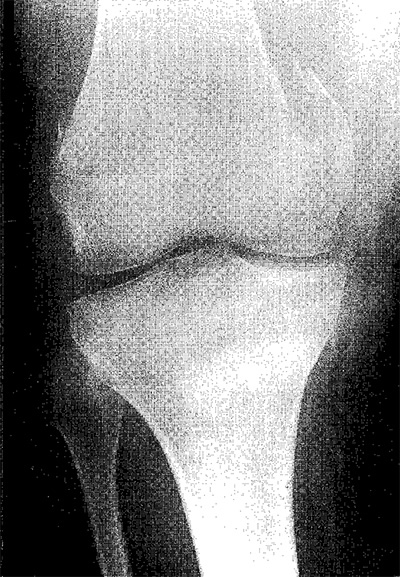

Pathological fractures

Although internal fixation of limb fractures sustained at the time of the spinal cord injury may often be indicated, particularly to assist nursing, the emphasis later is on a more conservative approach. After injury to the spinal cord, bones in the paralysed limbs become osteoporotic, and pathological fractures may occur with minimal or even no obvious trauma. A common injury is a supracondylar fracture of the femur caused by the patient falling out of the wheelchair on to his or her knees. Violent spasticity of the hip flexors, particularly if the leg rotates, can fracture the femoral shaft.

With rare exceptions treatment should be conservative. A well-padded splint may be enough. If a circular cast is used it should be split, allowing the skin to be inspected daily for signs of pressure. Insufficient padding or failure to split a cast on a paralysed limb carries a high risk of producing pressure sores and painless ischaemia secondary to swelling. Immobilisation should not be prolonged as it is important to avoid joint stiffness, which might limit the patient’s independence. It is particularly important to maintain the range of hip and knee movements, so that the patient’s posture in the wheelchair is unaffected. Fortunately, fracture healing is usually satisfactory and callus formation good. There may, however, be an exacerbation of spasticity in the injured limb, which can complicate management of the fracture.

Post-traumatic syringomyelia (syrinx, cystic myelopathy)

Post-traumatic syringomyelia, an ascending myelopathy due to secondary cavitation in the spinal cord, is seen in at least 4% of patients. Symptoms may appear as early as two months after injury or in rare instances be delayed for over 30 years, the average latent period having previously been reported as eight to nine years.

The commonest presenting symptom is pain in the arm, usually unilateral, described as a dull ache but occasionally as burning or stabbing. The syrinx also often extends below the level of the spinal cord lesion, and in these instances bladder and bowel function can be further affected. The earliest sign is usually a dissociated sensory loss, with impaired or absent pain and temperature sensation (spinothalamic loss) and preservation of light touch and joint position sense (posterior column sparing). Some patients also have sensory loss over the face due to an extension of the cavitation into the upper cervical cord, which affects the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve and, in rare instances, the brain stem. When present, motor loss is of a lower motor neurone type and is usually unilateral. Though there may be remissions, the condition may progress, perhaps even to the extent of converting low paraplegia into tetraplegia.

Though essentially clinical, the diagnosis is confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or in rare instances myelography with computed tomography (CT). Surgical treatment includes decompression or drainage of the syringomyelic cavity. Pain is usually relieved, but relief of sensory symptoms and motor loss is less predictable.

Pain

Pain relief in the acute stage of spinal cord injury has been discussed in chapters 1 and 4.

Chronic intractable pain after spinal cord injury is a particularly difficult problem, largely because of the profound emotional effect of a severe disability occurring suddenly and unexpectedly in a previously healthy and often young patient. A self-generating mechanism has been suggested for pain in the central nervous system, and it is possible, particularly in patients with incomplete spinal cord lesions, that abnormal sensations arising adjacent to the site of cord damage will act as stimuli for the subsequent development of chronic pain. The "conditioning" effect of early acute pain on the nervous system can be minimised by a sympathetic attitude towards the patient and prompt administration of adequate doses of analgesics to relieve pain from the site of bony injury. The spine should be realigned, nerve root compression relieved if necessary, and the limbs correctly positioned and regularly put through a full range of passive movements.

Factors contributing to chronic pain:

- Inadequate early pain relief of the spinal injury

- Spinal malalignment

- Nerve root compression

- Incompleteness of spinal cord lesion

- Poor emotional adjustment

During the first few weeks or months after injury discomfort or pain may occur, which appears to be related to neural damage rather than the musculoskeletal trauma. It may take one of several forms. There may be an unpleasant or painful sensation in a paralysed area similar to the phantom phenomenon experienced after amputation. Another example is an acute burning or stabbing sensation felt immediately below the neurological level of the lesion or several segments distally, which can be continuous and extremely incapacitating. This type of pain is often seen in cauda equina lesions. In incomplete lesions pain can also present as a burning sensation associated with hyperalgesia and may be increased by peripheral stimulation or movement of the limb. Pain that follows an anatomical distribution at or just below the level of the cord lesion may be due to damage at the root entry zone, but in these circumstances it is important to exclude nerve root compression, which may rarely require surgical decompression.

The number of patients who complain of severe chronic pain is considerable, and many others are aware of abnormal sensation below the level of the lesion. Continuing spinal instability must be treated, but otherwise mobilisation should begin as early as possible after injury, the distraction of full participation in a busy rehabilitation programme being the most helpful measure.

Proposed classification of pain related to spinal cord injury:

| Broad type (Tier 1) |

Broad system (Tier 2) |

Specific structures/pathology (Tier 3) |

| Nociceptive | Musculoskeletal | - Bone, joint, muscle trauma or inflammation - Mechanical instability - Muscle spasm - Secondary overuse syndromes |

| Visceral | - Renal calculus, bowel, sphincter dysfunction, etc. - Dysreflexic headache |

|

| Neuropathic | Above level | - Compressive mononeuropathies - Complex regional pain syndromes |

| At level | - Nerve root compression - Syringomyelia - Spinal cord trauma/ischemia (segmental deafferentation, transitional zone, border zone, girdle zone etc.) - Dual level cord and root trauma (double lesion syndrome) |

|

| Below level | - Spinal cord trauma/ischemia (central dysesthesia syndrome, central pain, phantom pain, etc.) |

Most analgesics do not satisfactorily relieve pain associated with neural damage, although tramadol does appear to be of benefit in some patients. Tricyclic antidepressants combined with anticonvulsants, for example gabapentin or carbamazepine, often help. Treatment of sleep disturbance is important. Following psychological assessment and support, other techniques including transcutaneous nerve stimulation, acupuncture, relaxation techniques, and hypnotherapy can also be used. Spinal cord (dorsal column) stimulation appears to have little place in treatment. The effect of surgical techniques such as posterior rhizotomy and spinothalamic tractotomy, which interrupt the pain pathways, may only have a short lasting effect, and also have little place in treatment, but dorsal root entry zone coagulation (DREZ lesion) appears to be of benefit in selected patients. Surgery for pain management should be limited to a few specialist centres.

Treatment of chronic pain:

- Treat spinal instability and nerve root compression

- Distraction by busy rehabilitation programme

- Psychological support

- Antidepressants — for example, amitryptyline

- Anticonvulsants — for example gabapentin, carbamazepine

- Transcutaneous nerve stimulation

- Acupuncture

- Hypnotherapy and relaxation techniques

- Dorsal root entry zone coagulation (DREZ lesion)

Sexual function

Sexual function depends on the level and completeness of the spinal cord lesion. If the lesion is incomplete sexual function may be affected to a varying degree and sometimes not at all. In women, although there is often an initial period of amenorrhoea after spinal cord injury, fertility is unimpaired. In men with complete or substantial spinal cord lesions, the ability to achieve normal erections, ejaculate, and father children can be greatly disturbed.

Spinal cord centres for sexual function:

| Erection | Reflex | Parasympathetic S2, 3, 4 (nervi erigentes) |

| Psychogenic | Sympathetic T11 to L2 (hypogastric nerve) | |

| Emission | Sympathetic T11 to L2 (hypogastric nerve) | |

| Ejaculation | Somatic S2, 3, 4 (pudendal nerve) | |

Erections

Most patients with complete upper motor neurone lesions of the cord have reflex, but not psychogenic, erections. However, the erections are not always sustained or strong enough for penetrative sex. In patients with complete lower motor neurone lesions parasympathetic connections from the S2 to S4 segments of the cord to the corpora cavernosa are interrupted, so that reflex erections are usually impossible.

Difficulty in achieving a satisfactory erection has been revolutionised by the introduction of sildenafil, which has often replaced the use of intracavernosal drugs such as alprostadil or vacuum erection aids and compressive retainer rings. Insertion of a penile implant is also possible, but carries a small risk of infection or erosion of the implant which will necessitate its removal. Some men with a sacral anterior nerve root stimulator are able to achieve stimulator-driven erections, in addition to using the stimulator primarily for micturition.

Emission and ejaculation

For seminal emission to occur the sympathetic outflow from T11 to L2 segments of the cord to the vasa deferentia, seminal vesicles, and prostate must be intact. Emission infers a trickling leakage of semen, with no rhythmic contractions of the pelvic floor muscles as in true ejaculation. Some patients with complete cord lesions at lumbar or sacral level may have both psychogenic erections and emissions.

If ejaculation is not possible during penetrative sexual intercourse, it may be induced by direct stimulation of the fraenum of the penis by masturbation or by using a vibrator. If this is unsuccessful, rectal electroejaculation may produce what is actually an emission.

In men who cannot ejaculate using the vibrator, or where electroejaculation is difficult, a hypogastric plexus stimulator can be implanted to obtain seminal emission, using a single inductive link across the skin. Men with lesions above T6 are at risk of autonomic dysreflexia developing during ejaculation. If this occurs activity should be curtailed, the man sat upright, and if necessary given sublingual nifedipine. Glyceryl trinitrate is also an effective treatment, but it is essential that patients are warned of the potentially fatal interaction of nitrates with sildenafil.

For men when neither emission nor ejaculation can be achieved it may be possible to collect spermatozoa by the technique of epididymal aspiration or testicular biopsy.

Preparation for sexual intercourse

Preparation for sexual intercourse includes ensuring that the bladder is as empty as possible. A man with an indwelling catheter should preferably remove it, but it may be strapped back on to the shaft of the penis. In the woman a catheter may be left in situ. The able-bodied partner tends to be the more active, and this has a bearing on the positions used for intercourse.

Aids to sexual function and fulfilment in relationships:

| To enhance sexual expression | - Use imagination, time and effort in touching parts of the body not affected by the injury, exploring both partners’ preferences, experimenting with other erotic stimuli, etc. |

| For erection | - Oral sildenafil - Intracavernosal drugs - Vacuum erection aid and compressive retainer ring - Penile implant (small risk of infection or extrusion) - Sacral anterior root stimulator |

| For ejaculation or seminal emission | - Vibrator - Electroejaculation unit - Hypogastric plexus stimulator |

| To collect spermatozoa | - Initial sperm culture - Retrieve collected spermatozoa by epididymal aspiration |

| Further assisted conception techniques | - Seminal fluid enhancement - Intrauterine insemination - In vitro fertilisation - Intracytoplasmic sperm injection |

| To counteract autonomic dysreflexia (possible in men during ejaculation, and in women during labour, if lesion above T6) | - Sublingual nifedipine or - Glyceryl trinitrate (potentially fatal interaction with sildenafil) |

Fertility

Fertility is generally reduced in men after spinal cord injury. The sperm count is usually low, with diminished motility due to various factors, probably including continuing non-ejaculation, raised testicular temperature, and infection. The quality of the seminal fluid may improve with repeated ejaculations, however, and successful insemination has been reported both with the vibrator and by electroejaculation. It is essential to obtain microbiological cultures of the seminal fluid and to eradicate any infection prior to proceeding with any attempt at fertilisation. The success rate has recently improved with the use of assisted conception techniques, including enhancement of seminal fluid, intrauterine insemination, and assisted reproductive technology, such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Labour

If the spinal cord lesion is complete above T10, labour may be painless and forceps delivery required because of inability to bear down effectively during the second stage of labour. Autonomic dysreflexia during labour is a risk in patients with lesions at T6 and above, but this complication can be prevented by epidural anaesthesia.

Labour:

- If lesion complete above T10, labour may be painless, therefore admit to hospital early, before labour commences

- Increased risk of assisted delivery because of paralysis of abdominal and pelvic muscles

- Risk of autonomic dysreflexia if lesion at T6 or above

Fulfilment in relationships

It should be emphasised that emotional and psychological factors are as important as physical factors in a satisfying relationship and that such a relationship is possible even after severe spinal cord injury. This needs reiterating, particularly to young men who are otherwise apt to see their altered sexual function as a profound loss. Although sensation in the sexual organs may be reduced or absent, imaginative use can be made of touching and caressing, as areas of the body above the level of the spinal cord lesion may develop heightened sensation as erogenous zones. Some couples find that the extra time and effort required for sexual expression after one of them has suffered a spinal cord injury enriches their lives and results in a more understanding and caring relationship.

Relationships:

- Emphasise importance of emotional and psychological factors

- Areas of body above level of paralysis can be used imaginatively and may develop heightened sensation

- Extra time and effort required can result in more understanding and caring relationship

See also

- At the accident:

- History and epidemiology of spinal cord injury

- Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

- Evacuation and initial management at hospital:

- Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Initial management of patients with spinal cord injuries at the receiving hospital

- Neurological assessment of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Spinal shock after severe spinal cord injury

- Partial spinal cord injury syndromes

- Radiological investigations:

- Initial radiography of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Cervical injuries

- Thoracic and lumbar injuries

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — I:

- Respiratory complications

- Cardiovascular complications

- Prophylaxis against thromboembolism

- Initial bladder management

- The gastrointestinal tract

- Use of steroids and antibiotics

- The skin and pressure areas

- Care of the joints and limbs

- Later analgesia

- Trauma re-evaluation

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — II:

- The anatomy of spinal cord injury

- The spinal injury (cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine)

- Transfer to a spinal injuries unit

- Medical management in the spinal injuries unit:

- The cervical spine injuries

- The cervicothoracic junction injuries

- Thoracic injuries

- Thoracolumbar and lumbar injuries

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Biochemical disturbances

- Para-articular heterotopic ossification

- Spasticity

- Contractures

- Pressure sores

- Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury:

- Nursing for people with spinal cord lesion:

- Physiotherapy after spinal cord injury:

- Respiratory management

- Mobilisation into a wheelchair

- Rehabilitation

- Recreation

- Incomplete lesions

- Children

- Occupational therapy after spinal cord injury:

- Hand and upper limb management

- Home resettlement

- Activities of daily living

- Communication

- Mobility

- Leisure

- Work

- Social needs of patient and family:

- Transfer of care from hospital to community:

- Education of patients

- Teaching the family and community staff

- Preparation for discharge from hospital

- Easing transfer from hospital to community

- Travel and holidays

- Follow-up

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — I:

- Late spinal instability and spinal deformity

- Pathological fractures

- Post-traumatic syringomyelia (syrinx, cystic myelopathy)

- Pain

- Sexual function

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — II:

- Later respiratory management of high tetraplegia

- Psychological factors

- The hand in tetraplegia

- Functional electrical stimulation

- Ageing with spinal cord injury

- Prognosis

- Spinal cord injury in the developing world: