Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

Doctors may witness or attend the scene of an accident, particularly if the casualty is trapped. Spinal injuries most commonly result from road trauma involving vehicles that overturn, unrestrained or ejected occupants, and motorcyclists. Falls from a height, high velocity crashes, and certain types of sports injury (e.g. diving into shallow water, collapse of a rugby scrum) should also raise immediate concern. Particular care must be taken moving unconscious patients, those who complain of pain in the back or neck, and those who describe altered sensation or loss of power in the limbs. Impaired consciousness (from injury or alcohol) and distracting injuries in multiple trauma are amongst the commonest causes of a failure to diagnose spinal injury. All casualties in the above risk categories should be assumed to have unstable spinal injuries until proven otherwise by a thorough examination and adequate x rays.

Spinal injuries involve more than one level in about 10% of cases. It must also be remembered that spinal cord injury without radiological abnormality (SCIWORA) can occur, and may be due to ligamentous damage with instability, or other soft tissue injuries such as traumatic central disc prolapse. SCIWORA is more common in children.

The unconscious patient

It must be assumed that the force that rendered the patient unconscious has injured the cervical spine until radiography of its entire length proves otherwise. Until then the head and neck must be carefully placed and held in the neutral (anatomical) position and stabilised. A rescuer can be delegated to perform this task throughout. However, splintage is best achieved with a rigid collar of appropriate size supplemented with sandbags or bolsters on each side of the head. The sandbags are held in position by tapes placed across the forehead and collar. If gross spinal deformity is left uncorrected and splinted, the cervical cord may sustain further injury from unrelieved angulation or compression. Alignment must be corrected unless attempts to do this increase pain or exacerbate neurological symptoms, or the head is locked in a position of torticollis (as in atlanto-axial rotatory subluxation). In these situations, the head must be splinted in the position found.

Thoracolumbar injury must also be assumed and treated by carefully straightening the trunk and correcting rotation. During turning or lifting, it is vital that the whole spine is maintained in the neutral position. While positioning the patient, relevant information can be obtained from witnesses and a brief assessment of superficial wounds may suggest the mechanism of injury — for example, wounds of the forehead often accompany hyperextension injuries of the cervical spine.

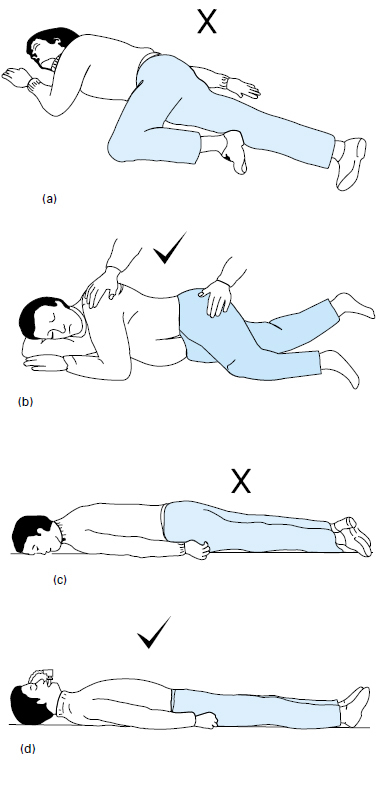

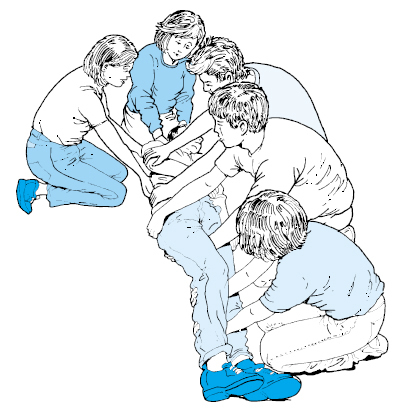

Although the spine is best immobilised by placing the patient supine, and this position is important for resuscitation and the rapid assessment of life threatening injuries, unconscious patients on their backs are at risk of passive gastric regurgitation and aspiration of vomit. This can be avoided by tracheal intubation, which is the ideal method of securing the airway in an unconscious casualty. If intubation cannot be performed the patient should be “log rolled” carefully into a modified lateral position 70–80˚ from prone with the head supported in the neutral position by the underlying arm. This posture allows secretions to drain freely from the mouth, and a rigid collar applied before the log roll helps to minimise neck movement. However, the position is unstable and therefore needs to be maintained by a rescuer. Log rolling should ideally be performed by a minimum of four people in a coordinated manner, ensuring that unnecessary movement does not occur in any part of the spine. During this manoeuvre, the team leader will move the patient’s head through an arc as it rotates with the rest of the body.

The prone position is unsatisfactory as it may severely embarrass respiration, particularly in the tetraplegic patient. The original semiprone coma position is also contraindicated, as it results in rotation of the neck. Modifications of the latter position are taught on first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation courses where the importance of airway maintenance and ease of positioning overrides that of cervical alignment, particularly for bystanders.

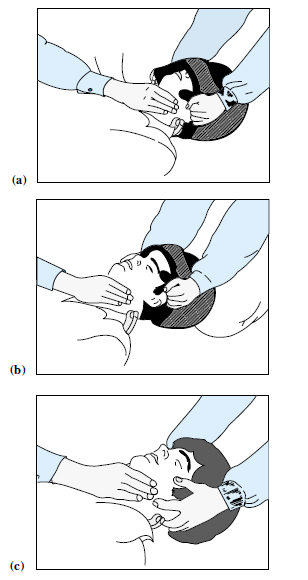

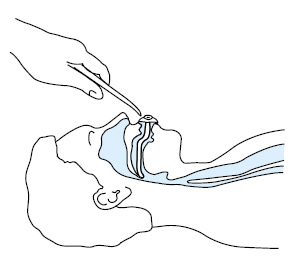

Patency of the airway and adequate oxygenation must take priority in unconscious patients. If the casualty is wearing a one-piece full-face helmet, access to the airway is achieved using a two-person technique: one rescuer immobilises the neck from below whilst the other pulls the sides of the helmet outwards and slides them over the ears. On some modern helmets, release buttons allow the face piece to hinge upwards and expose the mouth. After positioning the casualty and immobilising the neck, the mouth should be opened by jaw thrust or chin lift without head tilt. Any intra-oral debris can then be cleared before an oropharyngeal airway is sized and inserted, and high concentration oxygen given.

The indications for tracheal intubation in spinal injury are similar to those for other trauma patients: the presence of an insecure airway or inadequate arterial oxygen saturation (i.e. less than 90%) despite the administration of high concentrations of oxygen. With care, intubation is usually safe in patients with injuries to the spinal cord, and may be performed at the scene of the accident or later in the hospital receiving room, depending on the patient’s level of consciousness and the ability of the attending doctor or paramedic. Orotracheal intubation is rendered more safe if an assistant holds the head and minimises neck movement and the procedure may be facilitated by using an intubation bougie. Other specialised airway devices such as the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) or Combitube may be used but each has its limitations — for example the former device does not prevent aspiration and use of the latter device requires training.

If possible, suction should be avoided in tetraplegic patients as it may stimulate the vagal reflex, aggravate preexisting bradycardia, and occasionally precipitate cardiac arrest (to be discussed later). The risk of unwanted vagal effects can be minimised if atropine and oxygen are administered beforehand. In hospital, flexible fibreoptic instruments may provide the ideal solution to the intubation of patients with cervical fractures or dislocations.

Once the airway is protected intravenous access should be established as multiple injuries frequently accompany spinal cord trauma. However, clinicians should remember that in uncomplicated cases of high spinal cord injury (cervical and upper thoracic), patients may be hypotensive due to sympathetic paralysis and may easily be overinfused.

If respiration and circulation are satisfactory patients can be examined briefly where they lie or in an ambulance. A basic examination should include measurement of respiratory rate, pulse, and blood pressure; brief assessment of the level of consciousness and pupillary responses; and examination of the head, chest, abdomen, pelvis and limbs for obvious signs of trauma. Diaphragmatic breathing due to intercostal paralysis may be seen in patients with tetraplegia or high thoracic paraplegia, and flaccidity with areflexia may be present in the paralysed limbs. If the casualty’s back is easily exposed, spinal deformity or an increased interspinous gap may be identified.

The conscious patient

The diagnosis of spinal cord injury rests on the symptoms and signs of pain in the spine, sensory disturbance, and weakness or flaccid paralysis. In conscious patients with these features resuscitative measures should again be given priority. At the same time a brief history can be obtained, which will help to localise the level of spinal trauma and identify other injuries that may further compromise the nutrition of the damaged spinal cord by producing hypoxia or hypovolaemic shock. The patient must be made to lie down — some have been able to walk a short distance before becoming paralysed — and the supine position prevents orthostatic hypotension. A brief general examination should be undertaken at the scene and a basic neurological assessment made by asking patients to what extent they can feel or move their limbs.

Analgesia

![]() Attention! Opioid analgesics should be administered with care in patients with respiratory compromise from cervical and upper thoracic injuries.

Attention! Opioid analgesics should be administered with care in patients with respiratory compromise from cervical and upper thoracic injuries.

Clinical features of spinal cord injury:

- Pain in the neck or back, often radiating because of nerve root irritation

- Sensory disturbance distal to neurological level

- Weakness or flaccid paralysis below this level

In the acute phase of injury, control of the patient’s pain is important, especially if multiple trauma has occurred. Analgesia is initially best provided by intravenous opioids titrated slowly until comfort is achieved. Opioids should be used with caution when cervical or upper thoracic spinal cord injuries have been sustained and ventilatory function may already be impaired. Naloxone must be available. Careful monitoring of consciousness, respiratory rate and depth, and oxygen saturation can give warning of respiratory depression.

Intramuscular or rectal non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective in providing background analgesia.

See also

- At the accident:

- History and epidemiology of spinal cord injury

- Spinal injuries management at the scene of the accident

- Evacuation and initial management at hospital:

- Evacuation and transfer to hospital of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Initial management of patients with spinal cord injuries at the receiving hospital

- Neurological assessment of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Spinal shock after severe spinal cord injury

- Partial spinal cord injury syndromes

- Radiological investigations:

- Initial radiography of patients with spinal cord injuries

- Cervical injuries

- Thoracic and lumbar injuries

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — I:

- Respiratory complications

- Cardiovascular complications

- Prophylaxis against thromboembolism

- Initial bladder management

- The gastrointestinal tract

- Use of steroids and antibiotics

- The skin and pressure areas

- Care of the joints and limbs

- Later analgesia

- Trauma re-evaluation

- Early management and complications of spinal cord injuries — II:

- The anatomy of spinal cord injury

- The spinal injury (cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine)

- Transfer to a spinal injuries unit

- Medical management in the spinal injuries unit:

- The cervical spine injuries

- The cervicothoracic junction injuries

- Thoracic injuries

- Thoracolumbar and lumbar injuries

- Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autonomic dysreflexia

- Biochemical disturbances

- Para-articular heterotopic ossification

- Spasticity

- Contractures

- Pressure sores

- Urological management of patients with spinal cord injury:

- Nursing for people with spinal cord lesion:

- Physiotherapy after spinal cord injury:

- Respiratory management

- Mobilisation into a wheelchair

- Rehabilitation

- Recreation

- Incomplete lesions

- Children

- Occupational therapy after spinal cord injury:

- Hand and upper limb management

- Home resettlement

- Activities of daily living

- Communication

- Mobility

- Leisure

- Work

- Social needs of patient and family:

- Transfer of care from hospital to community:

- Education of patients

- Teaching the family and community staff

- Preparation for discharge from hospital

- Easing transfer from hospital to community

- Travel and holidays

- Follow-up

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — I:

- Late spinal instability and spinal deformity

- Pathological fractures

- Post-traumatic syringomyelia (syrinx, cystic myelopathy)

- Pain

- Sexual function

- Later management and complications after spinal cord injury — II:

- Later respiratory management of high tetraplegia

- Psychological factors

- The hand in tetraplegia

- Functional electrical stimulation

- Ageing with spinal cord injury

- Prognosis

- Spinal cord injury in the developing world: