Kidney stones (urolithiasis)

Understanding Kidney Stones (Urolithiasis)

Urolithiasis, commonly known as stone disease, is a condition characterized by the formation of stones (calculi) within the organs of the urinary system. While stones can form anywhere in the urinary tract, they most frequently develop in the kidneys (nephrolithiasis) and the urinary bladder (cystolithiasis).

Definition and Pathophysiology

The primary cause underlying the onset and development of urolithiasis is a metabolic disorder, often coupled with other contributing factors, which leads to the supersaturation of urine with certain minerals and salts. This supersaturation results in the crystallization and precipitation of these substances, forming insoluble particles that aggregate and grow into stones. The number, size, composition, and location of these stones can vary greatly among individuals.

Demographically, young to middle-aged adults most often present with stones located in the ureters and kidneys. Bladder stones, on the other hand, are more frequently diagnosed in elderly individuals (often related to bladder outlet obstruction) and in children (particularly in regions with specific dietary or endemic factors).

Predisposing Factors and Risk Factors

Urologists identify several key predisposing factors for the development of urolithiasis. These include:

- Metabolic Disorders:

- Hypercalciuria (excessive calcium in urine)

- Hyperoxaluria (excessive oxalate in urine)

- Hyperuricosuria (excessive uric acid in urine)

- Cystinuria (an inherited disorder causing excess cystine in urine)

- Hypocitraturia (low levels of citrate, a stone inhibitor, in urine)

- Dietary Factors:

- High intake of animal protein, oxalate-rich foods (e.g., spinach, rhubarb, nuts), sodium, or purines (for uric acid stones).

- Low fluid intake leading to concentrated urine.

- Certain composition of drinking water (e.g., hard water with high mineral content).

- Anatomical Malformations of the Urinary Tract: Conditions that cause urinary stasis or obstruction, such as ureteropelvic junction obstruction, horseshoe kidney, or medullary sponge kidney.

- Genetic Predisposition: Hereditary conditions like cystinuria or certain nephritis-like or nephrosis-like syndromes. A family history of kidney stones increases risk.

- Chronic Urogenital Diseases:

- Recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), especially with urease-producing bacteria (e.g., *Proteus*, *Klebsiella*), which can lead to struvite (infection) stones.

- Chronic pyelonephritis, cystitis, urocystitis, or inflammation of the prostate.

- Chronic Diseases of the Digestive System: Conditions like chronic gastritis, colitis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis), or intestinal malabsorption can alter urine composition.

- Systemic Conditions: Gout, hyperparathyroidism, renal tubular acidosis.

- Medications: Certain drugs like diuretics (e.g., triamterene), protease inhibitors (e.g., indinavir), topiramate, or excessive vitamin C or D supplementation.

- Immobilization: Prolonged bed rest can lead to bone demineralization and hypercalciuria.

- Climate: Hot climates leading to dehydration and concentrated urine.

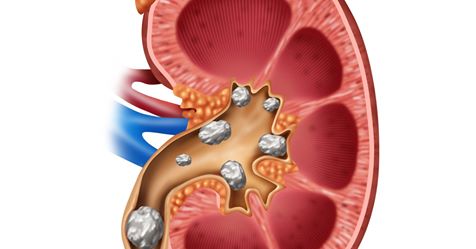

A staghorn calculus (coral stone) completely filling the renal collecting system in a kidney affected by urolithiasis, as identified on a CT scan of the abdominal organs. Such stones are often composed of struvite and associated with infection.

Diagnosis of Urolithiasis

Types of Kidney Stones

When diagnosing urolithiasis, stones are classified based on their chemical composition, which is crucial for understanding the reasons for their formation and for guiding preventive measures. The main types include:

- Calcium Stones (Calcium Oxalate and/or Calcium Phosphate): These are the most common type, accounting for up to 70-80% of all urinary calculi.

- Uric Acid Stones (Metabolic Stones): Occur in up to 5-12% of patients, often associated with high purine intake, gout, or acidic urine.

- Struvite Stones (Infection Stones or Triple Phosphate Stones): Composed of magnesium ammonium phosphate, these account for up to 10-15% of stones and are almost always associated with urinary tract infections caused by urease-producing bacteria. They can grow very large, sometimes forming staghorn calculi.

- Cystine Stones: Rare (up to 2-3% of patients), caused by an inherited metabolic disorder called cystinuria, which leads to excessive excretion of cystine in the urine.

- Other Rare Stones: Xanthine stones, drug-induced stones (e.g., indinavir).

Determination of the mineral composition of passed or removed stones is essential, particularly for patients with recurrent stone formation. After identifying the cause of stone formation, a comprehensive set of measures, known as **metaphylaxis**, is prescribed to prevent recurrent stone episodes.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation

The symptoms of urolithiasis largely depend on the location, size, and mobility of the stone(s), as well as the presence of obstruction or infection. The main symptoms include:

- Pain (Renal Colic): This is often the most dramatic symptom. It is typically characterized by sudden, severe, paroxysmal (intermittent and cramping) pain in the flank (loin area), which may radiate to the lower abdomen, groin, genitalia (testicles or labia), and inner thigh. The pain is caused by acute obstruction of urine flow and distension of the ureter or renal pelvis. Patients are often restless and unable to find a comfortable position.

- Hematuria (Blood in the Urine): Can be macroscopic (visible blood) or microscopic (detected only on urinalysis). It results from mucosal trauma as the stone moves.

- Nausea and Vomiting: Common during episodes of renal colic due to shared nerve pathways.

- Urinary Symptoms:

- Dysuria: Painful urination.

- Frequency: Increased need to urinate.

- Urgency: Sudden, strong urge to urinate. These are more common when a stone is in the lower ureter or bladder.

- Deterioration in General Well-being: Fatigue, malaise.

- Fever and Chills: If a urinary tract infection develops secondary to obstruction (obstructive pyelonephritis or pyonephrosis), this is a serious sign requiring urgent attention.

Symptom patterns based on stone location:

- Kidney Stone (Non-obstructing or in Calyx): May be asymptomatic or cause dull flank pain, often exacerbated by physical exertion or jolting movements. Other diseases of the genitourinary tract may worsen in patients with kidney stones.

- Bladder Stone: Can cause frequent, painful urination, interruption of the urinary stream, suprapubic pain, and pain or discomfort that appears or worsens with movement or at the end of urination.

- Ureteral Stone: Typically causes renal colic as described above. The location of pain may shift as the stone moves down the ureter. Frequent urge to urinate is common when the stone is near the bladder.

If a stone completely blocks the lumen of the ureter, urine accumulates in the kidney, leading to hydronephrosis and potentially severe renal colic. The colic continues until the stone changes position, allowing some urine to pass, or until the stone is expelled from the ureter.

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnosing urolithiasis involves a combination of clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and imaging studies:

- Medical History and Physical Examination: Including symptom details, dietary habits, fluid intake, family history of stones, and previous stone episodes. Physical exam may reveal flank tenderness.

- Urinalysis: To detect hematuria (microscopic or gross), pyuria (white blood cells indicating infection), bacteriuria, crystals (which can suggest stone type), and urine pH (acidic urine predisposes to uric acid and cystine stones; alkaline urine to struvite and calcium phosphate stones).

- Blood Tests: To assess kidney function (creatinine, BUN, eGFR), serum electrolytes, calcium, phosphorus, uric acid, and parathyroid hormone levels (if hyperparathyroidism is suspected).

- Imaging Studies:

- Non-Contrast Computed Tomography (CT) Scan of the Abdomen and Pelvis: This is the gold standard for detecting urinary stones (even radiolucent ones like uric acid stones), determining their size, location, and density, and identifying associated complications like hydronephrosis or signs of infection.

- Kidney-Ureter-Bladder (KUB) X-ray: Can visualize radiopaque stones (calcium-containing, struvite). Often used for follow-up.

- Renal Ultrasound: Useful for detecting kidney stones (especially within the kidney), hydronephrosis, and bladder stones. It is non-invasive and does not involve radiation, making it suitable for pregnant women and children. However, it is less sensitive for ureteral stones.

- Intravenous Pyelogram (IVP) / CT Urography: (IVP is less common now). Involves injecting contrast dye to visualize the urinary tract anatomy, identify stones, and assess obstruction and kidney function. CT Urography provides more detailed anatomical information.

- Stone Analysis: If a stone is passed or surgically removed, its chemical composition should be analyzed to guide preventive measures.

- 24-Hour Urine Collection: To measure urinary volume and excretion of calcium, oxalate, uric acid, citrate, sodium, creatinine, and other substances to identify metabolic risk factors for stone formation.

Treatment of Urolithiasis

The treatment of urolithiasis is conducted under the constant supervision of a physician (urologist) and depends on several factors, including the size, type, and location of the stone(s), the severity of symptoms, and the presence of complications like obstruction or infection. Treatment can range from conservative measures to various interventional procedures.

Conservative and Medical Management

This approach is often suitable for small stones (typically <5-6 mm) that are likely to pass spontaneously and for managing symptoms.

- Pain Management (for Renal Colic):

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or diclofenac are often first-line for pain relief.

- Opioid analgesics may be needed for severe pain.

- Antispasmodics (e.g., hyoscine butylbromide) can help relieve ureteral spasm.

- Thermal procedures (applying a heating pad to the flank, warm baths) can provide comfort.

- Novocaine (procaine) therapeutic injections or blocks were historically used for severe pain but are less common now.

- Medical Expulsive Therapy (MET): For small stones in the distal ureter, medications like alpha-blockers (e.g., tamsulosin) or calcium channel blockers (e.g., nifedipine) can be prescribed to relax the ureteral smooth muscle and facilitate stone passage. These drugs activate urodynamics and promote independent discharge of stones. Historically, medications like cystenal, artemizol, ennantin, and avisan were prescribed for stones up to 0.5 cm.

- Hydration: Increased fluid intake is encouraged to promote urine flow and help flush out small stones, unless contraindicated (e.g., severe obstruction where it might worsen pain).

- Antibacterial Drugs: If a urinary tract infection is present or suspected, appropriate antibiotics are prescribed.

- Chemoprophylaxis/Stone Dissolution (Chemolytholysis): For certain types of stones, medical therapy can help dissolve them or prevent further growth:

- Uric Acid Stones: Alkalinization of urine (e.g., with potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate) to a pH of 6.5-7.0 can help dissolve uric acid stones. Allopurinol may be used to reduce uric acid production.

- Cystine Stones: High fluid intake, urine alkalinization, and medications like D-penicillamine or tiopronin (which bind cystine) are used.

- Struvite stones require eradication of infection with antibiotics and often surgical removal of the stone.

- Dietary Modifications: Based on stone composition and 24-hour urine analysis (e.g., reducing sodium, oxalate, or purine intake; increasing citrate intake).

Surgical Treatment Options

Surgical or interventional treatment is indicated for stones that are too large to pass spontaneously, cause persistent pain, obstruction, infection, or kidney damage, or if medical management fails. Currently, many non-surgical or minimally invasive methods allow for good results without traditional open surgery.

Open Surgical Procedures (Less Common Today)

These are traditional open operations, now largely replaced by minimally invasive techniques for most stones.

- Pyelolithotomy: If the stone is located in the renal pelvis. The pelvis is surgically incised, the stone is removed, a suture is applied to the pelvis, and drainage may be placed.

- Nephrolithotomy: If a very large stone within the kidney cannot be removed through an incision in the pelvis alone. An incision is made through the kidney tissue (parenchyma) itself to access and remove the stone.

- Ureterolithotomy: If the stone is lodged in the ureter. The ureter is opened at the site of the stone, the stone is removed, and the ureter is repaired.

Endoscopic Surgery (Minimally Invasive)

These techniques involve accessing the urinary tract through natural orifices or small percutaneous incisions, using endoscopes (thin tubes with a camera and light source) and specialized instruments.

- Ureteroscopy (URS) with Lithotripsy and Lithoextraction:

- A thin ureteroscope is passed through the urethra and bladder into the ureter (and sometimes into the renal pelvis - ureteropyeloscopy).

- The ureter is examined under direct vision. If a stone is found:

- Small stones can be captured with a basket or grasper and removed (lithoextraction).

- Larger stones are first fragmented (lithotripsy) using a laser (e.g., Holmium laser), electrohydraulic lithotripter, or pneumatic lithotripter, and the pieces are then removed.

- This is performed in a specially equipped X-ray operating room or urological suite, often with fluoroscopic guidance.

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (PCNL) or Nephrolithotripsy:

- Used for larger kidney stones (typically >2 cm) or complex stones (e.g., staghorn calculi).

- A nephroscope is inserted into the renal collecting system (calyces and pelvis) through a small puncture tract created in the flank (lumbar region) under imaging guidance.

- Stones are fragmented using ultrasonic, pneumatic, or laser lithotripters and the pieces are suctioned out or removed with graspers.

Historically, transurethral X-ray endoscopic surgery involved destroying stones into small pieces under the surgeon's vision through a cystoscope tube. Modern nephroscopes and ureteropyeloscopes have made this a primary method for treating urolithiasis throughout the urinary tract.

Extracorporeal Shock-Wave Lithotripsy (ESWL)

ESWL is a non-invasive procedure that uses externally generated high-energy shock waves to break kidney or ureteral stones into small particles. These fragments then pass out of the body in the urine. A special reflector focuses electro-hydraulic, electromagnetic, or piezoelectric waves onto the stone from outside the patient's body, destroying it without direct contact. ESWL is suitable for certain types, sizes, and locations of stones, particularly those in the kidney or upper ureter that are not too large or hard.

Prevention of Recurrent Stone Formation (Metaphylaxis)

For patients with recurrent urolithiasis, preventing further stone formation is crucial. After determining the cause of stone formation (often through stone analysis and metabolic evaluation including 24-hour urine tests), a tailored set of measures (metaphylaxis) is prescribed. This may include:

- Increased Fluid Intake: Aiming for a urine output of at least 2-2.5 liters per day.

- Dietary Modifications: Specific to the type of stone (e.g., reducing oxalate for calcium oxalate stones, purines for uric acid stones, sodium for calcium stones).

- Medications:

- Thiazide diuretics (for hypercalciuria).

- Potassium citrate (to increase urine citrate and pH).

- Allopurinol (for hyperuricosuria).

- Specific medications for cystinuria.

- Lifestyle Changes: Weight management, regular exercise.

- Treatment of Underlying Conditions: E.g., hyperparathyroidism, recurrent UTIs.

Differential Diagnosis of Renal Colic / Flank Pain

Severe flank pain characteristic of renal colic must be differentiated from other acute abdominal or back conditions:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Urolithiasis (Renal Colic) | Sudden onset, severe, colicky flank pain radiating to groin/genitalia; patient restless; hematuria common; nausea/vomiting. Stone on imaging (CT gold standard). |

| Acute Pyelonephritis | Flank pain (often duller, constant), fever, chills, dysuria, urgency, frequency. Urinalysis shows pyuria, bacteriuria. Usually no acute colic unless obstruction present. |

| Appendicitis (especially retrocecal) | Pain often starts periumbilical, then localizes to right lower quadrant; nausea, vomiting, fever, anorexia. Specific abdominal signs (McBurney's point tenderness). |

| Diverticulitis | Usually left lower quadrant pain (sigmoid colon), fever, changes in bowel habits. More common in older adults. |

| Ovarian Cyst Rupture or Torsion (in females) | Sudden onset of sharp pelvic or lower abdominal pain, may radiate. Ultrasound is diagnostic. |

| Ectopic Pregnancy (in females of reproductive age) | Lower abdominal/pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, amenorrhea. Positive pregnancy test. Ultrasound. Medical emergency. |

| Biliary Colic / Cholecystitis | Right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, may radiate to back/shoulder. Often postprandial (after fatty meals). Nausea, vomiting. Murphy's sign. Ultrasound helpful. |

| Musculoskeletal Pain (e.g., Lumbago, Muscle Spasm) | Pain often related to movement or posture, localized tenderness over muscles/spine. No urinary symptoms. |

| Aortic Aneurysm (Dissecting or Ruptured) | Sudden, severe tearing back, abdominal, or chest pain. Hypotension, pulsatile abdominal mass. Medical emergency. |

Potential Complications of Kidney Stones

If not managed appropriately, kidney stones can lead to several complications:

- Urinary Tract Obstruction: Leading to hydronephrosis (swelling of the kidney) and impaired kidney function.

- Severe Pain (Renal Colic).

- Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs): Stagnation of urine above an obstructing stone predisposes to infection, which can lead to pyelonephritis or pyonephrosis (infected, obstructed kidney – a urological emergency).

- Kidney Damage: Chronic obstruction or recurrent infections can lead to irreversible loss of kidney function and chronic kidney disease.

- Sepsis: If an obstructed kidney becomes infected (pyonephrosis), it can lead to life-threatening urosepsis.

- Hematuria.

- Stricture Formation: Rarely, impacted stones can cause ureteral scarring and narrowing.

When to Consult a Urologist

Medical attention should be sought, and consultation with a urologist is often necessary, if:

- Severe pain suggestive of renal colic occurs.

- There is visible blood in the urine.

- Symptoms of a urinary tract infection (fever, chills, painful urination) accompany flank pain.

- Pain is not relieved by simple analgesics.

- There is inability to pass urine.

- Nausea and vomiting are persistent and prevent oral intake.

- A known stone sufferer experiences a change in their usual symptom pattern.

- Recurrent stone formation occurs, necessitating metabolic evaluation and preventive strategies.

A urologist specializes in diagnosing and managing kidney stones and can offer a range of treatments from medical therapy to minimally invasive procedures.

References

- Pearle MS, Goldfarb DS, Assimos DG, et al. Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2014 Aug;192(2):316-24.

- Türk C, Petřík A, Sarica K, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urolithiasis. European Association of Urology; 2023. (Refer to the latest EAU guidelines).

- Fink HA, Wilt TJ, Eidman KE, et al. Medical management to prevent recurrent nephrolithiasis in adults: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Apr 16;158(8):535-43.

- Moe OW. Kidney stones: pathophysiology and medical management. Lancet. 2006 Jan 28;367(9507):333-44.

- Preminger GM, Tiselius HG, Assimos DG, et al. 2007 guideline for the management of ureteral calculi. J Urol. 2007 Dec;178(6):2418-34.

- Scales CD Jr, Smith AC, Hanley JM, Saigal CS; Urologic Diseases in America Project. Prevalence of kidney stones in the United States. Eur Urol. 2012 Jul;62(1):160-5.

- Worcester EM, Coe FL. Nephrolithiasis. Prim Care. 2008 Jun;35(2):369-91, vii.

See also

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- Cystitis (Bladder Infection)

- Hydrocele (Testicular Fluid Collection)

- Kidney Stones (Urolithiasis)

- Kidney (Urinary) Syndromes & Urinalysis Findings

- Bilirubinuria and Urobilinogenuria

- Cylindruria (Casts in Urine)

- Glucosuria (Glucose in Urine)

- Hematuria (Blood in Urine)

- Hemoglobinuria (Hemoglobin in Urine)

- Ketonuria (Ketone Bodies in Urine)

- Myoglobinuria (Myoglobin in Urine)

- Proteinuria (Protein in Urine)

- Porphyrinuria (Porphyrins in Urine) & Porphyria

- Pyuria (Leukocyturia - WBCs in Urine)

- Orchitis & Epididymo-orchitis (Testicular Inflammation)

- Prostatitis (Prostate Gland Inflammation)

- Pyelonephritis (Kidney Infection)

- Hydronephrosis & Pyonephrosis

- Varicocele (Enlargement of Spermatic Cord Veins)

- Vesiculitis (Seminal Vesicle Inflammation)