Varicocele

- Understanding Varicocele

- Anatomical Features and Pathophysiology of Varicocele

- Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Varicocele

- Diagnosis of Varicocele

- Treatment of Varicocele

- Potential Complications and Impact on Fertility

- Differential Diagnosis of Scrotal Swelling/Pain

- When to Consult a Urologist

- References

Understanding Varicocele

Varicocele is defined as an abnormal dilation (expansion) and tortuosity (lengthening and twisting) of the pampiniform plexus of veins within the spermatic cord. The spermatic cord contains the structures that run to and from the testicle, including the vas deferens, arteries, nerves, and veins.

Definition and Prevalence

A slight, asymptomatic expansion of the veins of the spermatic cord, particularly on the left side, is relatively common and often does not produce subjective symptoms or require treatment. However, more significant varicoceles can lead to discomfort, testicular atrophy, and impaired fertility. Varicoceles are found in approximately 15% of the general male population and are a common identifiable cause of male infertility, found in about 35-40% of men with primary infertility and up to 80% of men with secondary infertility.

Primary vs. Secondary Varicocele

Varicoceles can be classified as:

- Primary (Idiopathic) Varicocele: This is the most common type and is usually due to incompetent or absent valves in the testicular (internal spermatic) vein, leading to retrograde (backward) blood flow and venous pooling. It predominantly affects the left side (around 85-90% of cases).

- Secondary Varicocele: This type is less common and results from compression or obstruction of the testicular vein along its course, impairing blood outflow. This can be caused by an abdominal or retroperitoneal mass, such as a tumor in the renal area (e.g., renal cell carcinoma compressing the left renal vein into which the left testicular vein drains), retroperitoneal fibrosis, or other masses. A new-onset varicocele, especially on the right side or one that does not decompress when lying down, should raise suspicion for a secondary cause.

Contributing Factors and Onset

Varicoceles most often develop during puberty, a period of rapid growth and hormonal changes. Factors considered to contribute to the occurrence or exacerbation of varicocele include:

- Hard Physical Labor or Strenuous Activity: Activities that increase intra-abdominal pressure.

- Prolonged Standing or Tiring Walking: Can increase hydrostatic pressure in the testicular veins.

- Adolescent Development: The onset of the disease in adolescence is sometimes associated with increased blood flow to the genitals during periods of growth and sexual arousal, potentially stressing the venous system.

- Genetic Predisposition: A family history may increase risk.

- Anatomical Factors: (Discussed further below).

Anatomical Features and Pathophysiology of Varicocele

Venous Anatomy of the Spermatic Cord

Several anatomical features of the veins of the spermatic cord (pampiniform plexus) contribute to the higher incidence of varicocele, especially on the left side:

- Valvular Incompetence: These veins often have imperfectly constructed or absent valves, particularly in the groin area, which normally prevent backward blood flow.

- Lack of Muscular Support: The veins of the spermatic cord run within loose connective tissue and do not receive the same degree of support from contracting muscles for venous emptying as do the veins of the extremities.

- Left-Sided Predominance – Anatomical Factors:

- The left testicular (internal spermatic) vein is longer than the right and drains into the left renal vein at a right angle (90 degrees). This perpendicular insertion can create higher hydrostatic pressure and impede smooth drainage compared to the right testicular vein, which drains obliquely into the inferior vena cava (IVC).

- The left testicle usually hangs slightly lower than the right, meaning the blood column pressure on the left side may be inherently higher.

- The left testicular vein can be compressed between the superior mesenteric artery and the aorta (the "nutcracker phenomenon"), or by a loaded sigmoid colon during constipation, further impairing drainage.

Any condition leading to diseases of the vascular system, particularly infections and intoxications, can potentially contribute to the onset of varicocele by weakening venous walls or damaging valves.

Pathological Changes and Impact on Testicles

The varicocele often begins with dilation of the anterior bundle of veins in the pampiniform plexus, but in advanced cases, the posterior bundle is also affected. Typically, the condition is limited to the veins of the spermatic cord, but sometimes painful changes can extend to the veins of the scrotal skin and penis. Occasionally, the veins within the testicle itself (intratesticular varicocele) are affected.

The stretched, convoluted, blood-filled veins of the cord sag under gravity, often forming a palpable "bag of worms" below and around the testicle. In severe cases, this can alter the position of the testicle, bringing it closer to a horizontal lie.

Impaired blood circulation and venous stasis due to varicocele can lead to several adverse effects on the testicle:

- Increased Scrotal Temperature: Pooling of warmer venous blood can elevate testicular temperature, impairing spermatogenesis (sperm production) and sperm quality.

- Hypoxia and Oxidative Stress: Venous stasis can lead to reduced oxygen supply and accumulation of metabolic waste products, causing oxidative stress.

- Reflux of Adrenal/Renal Metabolites: On the left side, reflux of adrenal or renal metabolites down the testicular vein into the pampiniform plexus has been postulated to have detrimental effects.

- Testicular Atrophy: These factors can lead to degenerative processes within the testicle itself, potentially resulting in its atrophy (shrinkage) and impaired function. During the period of illness, the affected testicle may feel flabby or have a reduced consistency.

- Associated Hydrocele: Swelling of the testicle or a reactive hydrocele (fluid collection around the testicle) can be a concomitant phenomenon.

Often, individuals with varicocele may also exhibit varicosities (dilated veins) in other areas of the body, such as the limbs or rectum (hemorrhoids), suggesting a possible systemic predisposition to venous insufficiency. Pathohistological changes in the veins of the spermatic cord with varicocele are similar to those observed in varicose veins of the extremities, including thinning of the venous wall, loss of elastic fibers, and smooth muscle atrophy.

Symptoms and Clinical Presentation of Varicocele

In many cases, especially with small varicoceles (Grade 1), individuals experience mild or no pain and the condition may be discovered incidentally during a physical examination or fertility evaluation.

In more advanced or symptomatic cases of varicocele, patients may complain of:

- Scrotal Heaviness or Dull Ache: A feeling of heaviness, dragging, or a dull, aching pain in the scrotum, particularly on the affected side.

- Pain Characteristics: The discomfort often worsens with prolonged standing, physical exertion, or during hot weather, and is typically relieved by lying down (which allows the veins to drain more easily).

- Pain Radiation: Pain may radiate to the groin, perineum, or lower back.

- Visible or Palpable Swelling: A soft, non-tender swelling ("bag of worms") along the spermatic cord, which consists of the bundle of dilated, convoluted veins. This swelling typically increases in the standing position or with Valsalva maneuver (straining) and decreases or disappears when lying down.

- Testicular Atrophy: The affected testicle may be smaller or softer than the contralateral one.

- Infertility: Varicocele is a common correctable cause of male infertility due to its adverse effects on sperm production and quality.

- Psychological Impact: Occasionally, patients with varicocele may experience anxiety, hypochondria, or concerns about sexual function (though direct impotence is not typically caused by varicocele itself unless psychological factors are significant).

On examination, the varicocele is typically more prominent when the patient is standing. Careful pressure can often decompress the bundle of dilated veins, making the swelling temporarily less apparent. The corresponding half of the scrotum may appear elongated or pear-shaped due to the sagging varicocele.

Diagnosis of Varicocele

The diagnosis of varicocele is primarily based on physical examination, often supplemented by imaging if needed.

- Physical Examination:

- Performed with the patient in both standing and supine (lying down) positions.

- Inspection for visible scrotal asymmetry or dilated veins.

- Palpation of the spermatic cord to detect the characteristic "bag of worms" feel of a varicocele.

- The Valsalva maneuver (asking the patient to bear down) can accentuate the varicocele by increasing intra-abdominal pressure and venous reflux.

- **Grading of Varicocele (Clinical):**

- Grade 1 (Small): Palpable only during Valsalva maneuver.

- Grade 2 (Moderate): Palpable at rest (without Valsalva) but not visible.

- Grade 3 (Large): Easily visible through the scrotal skin at rest.

- Assessment of testicular size and consistency to check for atrophy.

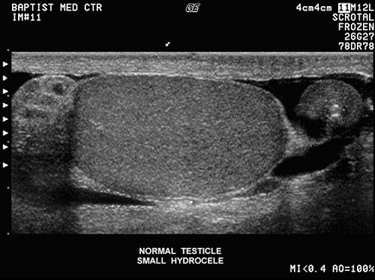

- Scrotal Doppler Ultrasound: This is the imaging modality of choice to confirm the diagnosis, especially for subclinical varicoceles (not easily palpable), to assess the degree of venous dilation (vein diameter >2.5-3 mm is often considered abnormal), and to detect reflux of blood in the testicular veins during Valsalva maneuver. It can also evaluate testicular volume and rule out other scrotal pathologies.

- Semen Analysis: If infertility is a concern, semen analysis is performed to evaluate sperm count, motility, morphology, and other parameters. Typical findings in varicocele-associated infertility include oligospermia (low sperm count), asthenospermia (poor motility), and teratospermia (abnormal morphology), often referred to as the "stress pattern."

- Hormonal Evaluation: Serum follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and testosterone levels may be checked if testicular dysfunction or infertility is significant. Elevated FSH can indicate primary testicular damage.

- Further Imaging (for suspected secondary varicocele): If a secondary varicocele is suspected (e.g., acute onset, right-sided, non-decompressible supine), imaging of the abdomen and retroperitoneum (e.g., ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI) is necessary to rule out a compressive mass or renal tumor.

Treatment of Varicocele

The management of varicocele depends on the presence and severity of symptoms, testicular atrophy, semen abnormalities, and the patient's fertility goals. Gradations in treatment are possible depending on the development of painful symptoms.

Conservative Management

For asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic varicoceles, especially in individuals not concerned about fertility, conservative management may be appropriate. This includes:

- Observation and Reassurance.

- Scrotal Support: Wearing a well-adapted suspensory or snug-fitting underwear to provide support and alleviate discomfort or heaviness. The suspensory should be worn so that there is no undue pressure on the groin area.

- Lifestyle Modifications: Avoiding activities that exacerbate discomfort (e.g., prolonged standing, heavy lifting). Eliminating constipation.

- Pain Relief: NSAIDs for occasional pain.

First of all, with varicocele, it is necessary to eliminate factors that complicate the outflow of blood from the veins of the spermatic cord, such as chronic constipation or prolonged physical fatigue.

Surgical Interventions (Varicocelectomy)

If conservative measures are ineffective, or if there is significant pain, testicular atrophy (especially progressive atrophy in adolescents), or abnormal semen parameters in an infertile man, surgical intervention (varicocelectomy) is necessary. The goal of surgery is to ligate or occlude the dilated testicular veins, thereby preventing retrograde blood flow and venous pooling.

Several surgical approaches exist, with the most common method to date being the **excision or ligation of the dilated veins of the spermatic cord**. Common techniques include:

- Inguinal or Subinguinal Microsurgical Varicocelectomy: Considered by many as the gold standard due to high success rates and low complication rates. Performed through a small incision in the groin, using an operating microscope to meticulously identify and ligate all internal spermatic veins and collateral veins while preserving the testicular artery, vas deferens, and lymphatic vessels.

- Laparoscopic Varicocelectomy: A minimally invasive approach where veins are clipped or ligated intra-abdominally.

- Retroperitoneal (Palomo) Approach: High ligation of the testicular vein, less common now.

Historically, an operation for varicocele involved exposing the spermatic cord, isolating the bundle of dilated veins from the artery and vas deferens, and excising this bundle between two ligatures. The lower segment was sometimes pulled upwards to elevate the testicle, which is often lowered in this disease. While this surgery for varicocele was usually beneficial, it could lead to long-term issues in the postoperative period, such as swelling of the cord tissue and associated pain. Relapses of varicocele were also possible. Furthermore, dissection of veins with inevitable trauma to other elements of the spermatic cord could adversely affect blood circulation and lymphatic drainage in the testicle itself, potentially leading to hydrocele formation or testicular damage.

Percutaneous Embolization

This is a minimally invasive radiological procedure where a catheter is inserted (usually via the femoral or jugular vein) and advanced to the testicular vein under fluoroscopic guidance. Small coils or sclerosing agents are then deployed to occlude the incompetent veins. It is an alternative to surgery, particularly for recurrent varicoceles or patients who prefer a less invasive option, but availability and expertise may vary.

Potential Complications and Impact on Fertility

If left untreated, significant varicoceles can lead to:

- Male Infertility: Impaired sperm production (count, motility, morphology) due to increased testicular temperature, hypoxia, and oxidative stress. Varicocele repair can improve semen parameters and pregnancy rates in some infertile men.

- Testicular Atrophy: Shrinkage of the affected testicle. Repair in adolescents with testicular atrophy may allow for catch-up growth.

- Chronic Scrotal Pain or Discomfort.

- Hypogonadism (Low Testosterone): In some cases, varicoceles may be associated with impaired Leydig cell function and reduced testosterone production.

Complications of varicocele treatment (surgery or embolization) can include:

- Hydrocele formation (common after some older surgical techniques, less so with microsurgery).

- Persistence or recurrence of varicocele.

- Testicular artery injury (rare with microsurgery).

- Infection, bleeding, chronic pain.

- Complications related to anesthesia.

Differential Diagnosis of Scrotal Swelling/Pain

A varicocele needs to be differentiated from other causes of scrotal swelling or pain:

| Condition | Key Differentiating Features |

|---|---|

| Varicocele | Soft, "bag of worms" feel along spermatic cord, increases with standing/Valsalva, decreases supine. Usually left-sided. Doppler US shows dilated veins with reflux. |

| Hydrocele | Fluid collection around testis; smooth, fluctuant scrotal swelling. Transilluminates. Usually painless unless tense or infected. |

| Spermatocele (Epididymal Cyst) | Smooth, firm, cystic mass usually at the head of the epididymis, separate from testis. Often asymptomatic. |

| Epididymitis/Orchitis | Acute onset of pain, swelling, redness, warmth of epididymis and/or testis. Often with fever, urinary symptoms. Doppler US shows increased blood flow. |

| Testicular Torsion | Sudden, severe testicular pain, nausea/vomiting. Testis often high-riding, transverse. Absent cremasteric reflex. Doppler US shows absent/decreased blood flow. **Surgical emergency.** |

| Inguinal Hernia | Swelling in groin/scrotum, may extend into scrotum. Reducible (often). Bowel sounds may be heard. Increases with coughing/straining. |

| Testicular Tumor | Firm, often painless mass within the testis. Does not transilluminate. US is key for diagnosis. |

When to Consult a Urologist

Consultation with a urologist is recommended if:

- A varicocele is suspected or detected on self-examination or by a physician.

- There is scrotal pain, discomfort, or a feeling of heaviness.

- One testicle appears smaller than the other (testicular atrophy).

- A couple is experiencing male factor infertility and a varicocele is present.

- An adolescent boy is found to have a varicocele, especially if it is large, associated with pain, or if there is a size discrepancy between the testicles.

- A varicocele appears suddenly, is on the right side only, or does not decompress when lying down (to rule out a secondary cause).

A urologist can confirm the diagnosis, assess the severity, discuss the potential impact on fertility and testicular health, and recommend appropriate management options.

References

- Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Report on varicocele and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2014 Sep;102(3):649-52.

- Agarwal A, Deepinder F, Cocuzza M, et al. Efficacy of varicocelectomy in improving semen parameters: new meta-analytical approach. Urology. 2007 Dec;70(6):1111-7.

- Schlegel PN. Is assisted reproduction the optimal treatment for varicocele-associated male infertility? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Urology. 1997 Jan;49(1):83-90.

- Jarow JP. Effects of varicocele on male fertility. Hum Reprod Update. 2001 Jul-Aug;7(4):469-72.

- European Association of Urology (EAU). Guidelines on Male Infertility. (Refer to latest version).

- Baazeem A, Belzile E, Ciampi A, et al. Effect of varicocelectomy on semen parameters: a meta-analysis. J Urol. 2011 Aug;186(2):571-6.

- Goldstein M, Gilbert BR, Dicker AP, Dwosh J, Gnecco C. Microsurgical inguinal varicocelectomy with delivery of the testis: an artery and lymphatic sparing technique. J Urol. 1992 Dec;148(6):1808-11.

- Cayan S, Kadioglu A, Orhan I, Kandirali E, Tefekli A, Tellaloglu S. The effect of microsurgical varicocelectomy on serum follicle stimulating hormone, testosterone and free testosterone levels in infertile men with varicocele. BJU Int. 1999 Oct;84(6):1046-9.

See also

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH)

- Cystitis (Bladder Infection)

- Hydrocele (Testicular Fluid Collection)

- Kidney Stones (Urolithiasis)

- Kidney (Urinary) Syndromes & Urinalysis Findings

- Bilirubinuria and Urobilinogenuria

- Cylindruria (Casts in Urine)

- Glucosuria (Glucose in Urine)

- Hematuria (Blood in Urine)

- Hemoglobinuria (Hemoglobin in Urine)

- Ketonuria (Ketone Bodies in Urine)

- Myoglobinuria (Myoglobin in Urine)

- Proteinuria (Protein in Urine)

- Porphyrinuria (Porphyrins in Urine) & Porphyria

- Pyuria (Leukocyturia - WBCs in Urine)

- Orchitis & Epididymo-orchitis (Testicular Inflammation)

- Prostatitis (Prostate Gland Inflammation)

- Pyelonephritis (Kidney Infection)

- Hydronephrosis & Pyonephrosis

- Varicocele (Enlargement of Spermatic Cord Veins)

- Vesiculitis (Seminal Vesicle Inflammation)