Tumor markers tests (cancer biomarkers)

- Key Takeaways for Patients

- Tumor Markers Overview

- What are Tumor Markers?

- Role in Personalized Medicine

- Clinical Uses of Tumor Markers

- Characteristics of an Ideal Tumor Marker

- Limitations and Considerations

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

- Tumor Markers in Monitoring

- Examples of Common Tumor Markers

- The Future of Cancer Biomarkers

- How Tumor Marker Tests are Performed

- Glossary of Tumor Marker Terms

- References

A Quick Guide for Patients

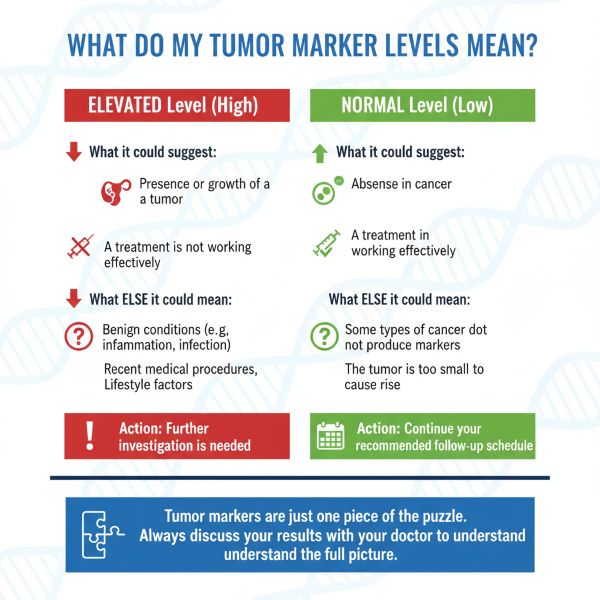

- Not a Standalone Test: Tumor marker results are never used alone. They are one piece of a larger puzzle that includes your symptoms, imaging scans, and biopsies.

- High Levels Don't Always Mean Cancer: Many non-cancerous conditions (like inflammation or infection) can raise tumor marker levels. A high result is a signal to investigate further, not a final diagnosis.

- Normal Levels Don't Rule Out Cancer: Some cancers don't produce markers, or levels may be normal in the early stages. Always follow your doctor's full monitoring plan.

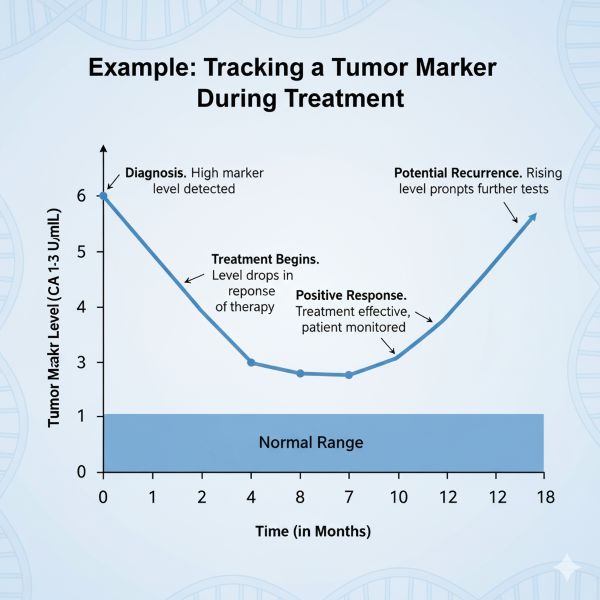

- The Trend is What Matters: For monitoring, a single result is less important than the trend over time. A consistent rise or fall in levels provides the most useful information.

Tumor Markers Overview

Cancer remains a major global health challenge, being a leading cause of mortality after cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. While advances in prevention and treatment are ongoing, early diagnosis is critical for improving outcomes. Unfortunately, many cancers are detected at later stages when they have already spread (generalized or metastasized), making successful treatment more difficult.

Detecting malignant tumors in their early stages significantly increases the likelihood of successful treatment, potentially leading to cure in up to 90% of cases. In oncology, laboratory tests that measure specific substances known as tumor markers (or cancer biomarkers) play an important role alongside imaging and pathology in the management of cancer patients.

These markers can aid in screening high-risk individuals, supporting diagnosis, determining prognosis, monitoring treatment effectiveness, and detecting cancer recurrence or metastasis earlier than might be possible with imaging or clinical symptoms alone.

What are Tumor Markers?

The terms "tumor markers" or "cancer biomarkers" encompass a broad and diverse group of biological substances that are produced either by cancer cells themselves or by the body in response to cancer. Their presence, or changes in their levels, can be correlated with the existence or progression of a malignant process.

These markers can have various biochemical characteristics, including:

- Oncofetal Antigens: Proteins normally produced during fetal development but re-expressed by some cancer cells (e.g., AFP, CEA).

- Oncoplacental Antigens: Proteins normally produced by the placenta (e.g., hCG).

- Tumor-Associated Antigens: Often glycoproteins or mucins overexpressed or altered on the surface of cancer cells (e.g., CA 15-3, CA 125, CA 19-9, MCA).

- Enzymes: Isoenzymes produced in higher amounts by certain tumors (e.g., NSE, LDH, PSA - prostatic acid phosphatase less used now).

- Hormones: Produced ectopically by non-endocrine tumors or excessively by endocrine tumors (e.g., Calcitonin in MTC, hCG).

- Oncogene Products or Related Proteins: Proteins related to cancer-causing genes (e.g., HER2 in tissue).

- Plasma Proteins: Specific proteins whose levels change significantly (e.g., Beta-2 Microglobulin in myeloma/lymphoma).

- Metabolic Products.

- Bioactive Peptides.

- Genetic Markers: Mutations or alterations in DNA/RNA found in tumor tissue or circulating in blood (liquid biopsy) - an expanding area.

These markers are typically measured in blood (serum or plasma), urine, or tumor tissue itself.

The Role of Biomarkers in Personalized Medicine

Beyond traditional tumor markers, the field is rapidly advancing with genetic and molecular biomarkers. These markers, such as KRAS, BRAF, and HER2, provide critical information about the specific genetic makeup of a tumor. This allows oncologists to move beyond one-size-fits-all treatments and select highly specific targeted therapies or immunotherapies that are most likely to be effective against a patient's unique cancer, minimizing side effects and improving outcomes.

Clinical Uses of Tumor Markers

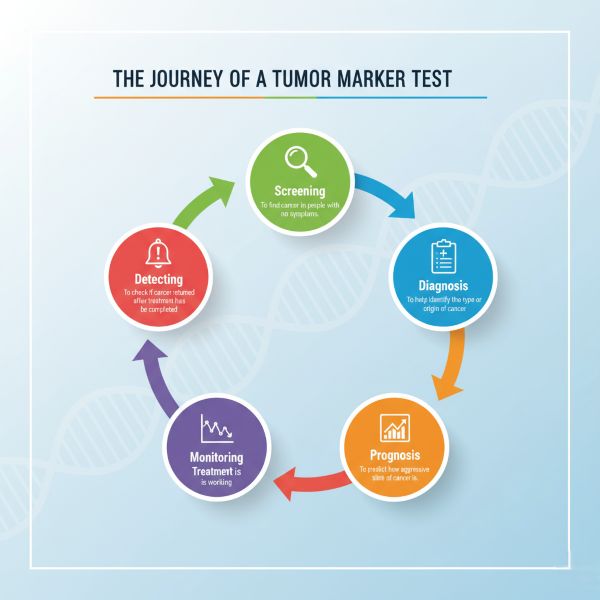

Tumor markers have several potential applications in oncology, although their utility varies greatly depending on the specific marker and cancer type:

- Screening: Detecting cancer in asymptomatic individuals. Only a few markers are suitable for screening specific high-risk populations (e.g., PSA for prostate cancer - controversial, AFP for HCC in cirrhosis patients, low-dose CT for lung cancer screening - not a blood marker). Most markers lack the specificity needed for general population screening.

- Diagnosis: Helping to establish a diagnosis, often in conjunction with imaging and biopsy. Few markers are diagnostic on their own, but some (like very high AFP/hCG for GCTs, high Calcitonin for MTC) can be highly suggestive. They can sometimes aid in differential diagnosis when the primary tumor site is unknown (e.g., NSE suggests neuroendocrine origin).

- Staging & Prognosis: The level of a tumor marker at diagnosis can sometimes correlate with the stage (extent) of the cancer and provide prognostic information (predicting likely outcome or aggressiveness).

- Monitoring Treatment Effectiveness: A significant decrease in an elevated marker level after treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, radiation) typically indicates a positive response. Failure to decline or subsequent increases suggest treatment resistance or failure.

- Detecting Recurrence: A rise in tumor marker levels during follow-up after initial remission can be the earliest sign of cancer recurrence or metastasis, often preceding clinical symptoms or imaging findings. This allows for earlier initiation of salvage therapy.

Characteristics of an Ideal Tumor Marker

The "ideal" tumor marker would possess several key characteristics, though no current marker meets all these criteria perfectly:

- High Specificity: Found only in patients with a specific type of cancer and not in healthy individuals or those with benign diseases (minimizing false positives).

- High Sensitivity: Detectable even when the tumor is very small (early stage) and present in almost all patients with that cancer (minimizing false negatives).

- Organ Specificity: Produced only by the tumor originating in a specific organ.

- Correlation with Tumor Burden: Levels should directly correlate with the amount of cancer present (tumor size, stage).

- Correlation with Treatment Response: Levels should accurately reflect the success or failure of treatment.

- Prognostic Value: Levels should help predict the likely course and outcome of the disease.

- Predictive Value: Levels might help predict whether a patient will respond to a specific therapy.

- Easy and Reliable Measurement: Test should be reproducible, readily available, and relatively inexpensive.

Limitations and Considerations

It is crucial to understand the limitations when using tumor markers:

- Lack of Specificity: Many tumor markers can be elevated in benign (non-cancerous) conditions (e.g., inflammation, infection, liver or kidney disease), leading to false-positive results and unnecessary anxiety or further testing.

- Lack of Sensitivity: Not all cancers of a specific type produce the associated marker, and levels may not be elevated in early-stage disease, leading to false-negative results. A normal tumor marker level does not rule out cancer or recurrence.

- Lead-Time Bias: Detecting recurrence earlier with a marker might not always translate into improved survival if effective salvage therapy is not available.

- Heterogeneity: Tumors can be diverse, and not all cells within a tumor may produce the marker consistently.

- Combination Testing: Due to the limitations of single markers, using a panel of several different markers is sometimes employed to improve sensitivity or specificity for certain cancers (e.g., AFP + hCG for germ cell tumors).

Therefore, tumor marker results must always be interpreted in the context of the patient's overall clinical picture, including history, physical examination, imaging studies, and pathology results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

If my tumor marker level is high, does it definitely mean I have cancer?

Not necessarily. Many tumor markers can be elevated due to benign (non-cancerous) conditions like inflammation, infection, or other diseases. A high level is a signal for your doctor to conduct further tests, such as imaging or a biopsy, to determine the cause. It is a piece of the puzzle, not a final answer.

What does a normal tumor marker level mean?

A normal level is a good sign, but it does not completely rule out cancer. Some cancers do not produce markers, or the tumor may be too small to cause a detectable increase. That is why doctors rely on a combination of tests and regular follow-ups, not just tumor markers.

Why do I need to repeat the test? Isn't one result enough?

In cancer monitoring, the trend is more important than a single result. A series of tests over time shows your doctor whether the marker level is rising, falling, or stable. A falling level suggests treatment is working, while a consistently rising level may be the earliest sign of recurrence.

Tumor Markers in Monitoring

One of the most valuable applications of tumor markers is in monitoring patients already diagnosed with cancer.

- Baseline Level: Establishing a baseline level before starting treatment is important.

- Post-Treatment Decline: The rate at which a marker level decreases after surgery or during chemo/radiotherapy can indicate treatment effectiveness and predict prognosis. The time it takes for the marker to return to normal (its half-life) is relevant.

- Surveillance for Recurrence: Serial measurements during follow-up can detect a rise in marker levels, often signalling recurrence before it becomes clinically apparent. This requires consistent testing intervals and careful interpretation of trends rather than single values.

- Reliability for Action: Ideally, a rising marker indicative of relapse should be reliable enough to prompt further investigation (e.g., imaging) or even treatment decisions, sometimes even before definitive radiological or cytological confirmation (though this depends heavily on the specific marker and clinical context).

Examples of Common Tumor Markers

Below are Tumor Markers Table commonly used in clinical practice:

| Tumor Marker | Associated Cancers/Conditions | Normal Adult / Pregnancy Levels | Interpretation and Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) | Liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma), germ cell tumors (e.g., testicular, ovarian), yolk sac tumors | Normal: <10 ng/mL Pregnancy: Elevated (10–150 ng/mL in second trimester) |

Notes: Also elevated in non-cancerous conditions like hepatitis or pregnancy. |

| Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) | Germ cell tumors (e.g., testicular, ovarian), gestational trophoblastic disease (e.g., choriocarcinoma, molar pregnancy) | Normal: <5 mIU/mL (non-pregnant) Pregnancy: Highly elevated (e.g., 10,000–200,000 mIU/mL) |

Notes: Useful for monitoring treatment response in these cancers. |

| Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) | Colorectal cancer, lung cancer, breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer | Normal: <5 ng/mL (non-smokers); <10 ng/mL (smokers) Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Non-specific; also elevated in benign conditions like smoking or inflammatory bowel disease. |

| CA 15-3 / CA 27.29 / CA 549 | Breast cancer | Normal: <30 U/mL (CA 15-3); <40 U/mL (CA 27.29); <10 U/mL (CA 549) Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Primarily used for monitoring advanced breast cancer and treatment response. |

| CA 19-9 | Pancreatic cancer, biliary tract cancer (cholangiocarcinoma), gastric cancer, colorectal cancer | Normal: <37 U/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Limited specificity; can be elevated in benign pancreatic or biliary diseases. |

| CA 125 | Ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer | Normal: <35 U/mL Pregnancy: May be mildly elevated |

Notes: Also elevated in benign conditions like endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease. |

| Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) | Prostate cancer | Normal: <4 ng/mL (age-dependent) Pregnancy: Not applicable (male-specific) |

Notes: Used for screening, diagnosis, and monitoring; elevated in benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or prostatitis. |

| Calcitonin | Medullary thyroid cancer | Normal: <10 pg/mL (men); <5 pg/mL (women) Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Highly specific; also used to monitor recurrence post-treatment. |

| Thyroglobulin (Tg) | Differentiated thyroid cancer (post-thyroidectomy) | Normal: <1 ng/mL (post-thyroidectomy) Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Used to monitor for recurrence; requires absence of thyroid tissue. |

| Neuron-specific enolase (NSE) | Small cell lung cancer, neuroblastoma, neuroendocrine tumors | Normal: <13 ng/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Useful for prognosis and monitoring treatment response. |

| Cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) | Non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancers | Normal: <3.3 ng/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Useful for prognosis in lung cancer. |

| Squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC) | Cervical cancer, squamous cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, esophageal cancer | Normal: <1.5 ng/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Limited sensitivity for early-stage disease. |

| β-2 microglobulin (B2M) | Multiple myeloma, lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Normal: <2.5 mg/L Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Also used to assess kidney function and prognosis in hematologic malignancies. |

| Mucin-like carcinoma-associated antigen (MCA) | Breast cancer | Normal: <11 U/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Less commonly used; often combined with other markers like CA 15-3. |

| S100 protein | Melanoma, schwannomas, some sarcomas | Normal: <0.15 µg/L Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Less common as a blood marker now; more often used in tissue staining. |

| Tissue polypeptide antigens (TPA, TPS) | Various cancers (measure cell proliferation; non-specific) | Normal: <80 U/L (TPA); <3 U/L (TPS) Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Limited specificity; used in combination with other markers. |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | Lymphoma, leukemia, germ cell tumors, melanoma, neuroblastoma | Normal: 140–280 U/L (varies by lab) Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Non-specific; elevated in many cancers and non-cancerous conditions (e.g., hemolysis, tissue damage). |

| Chromogranin A (CgA) | Neuroendocrine tumors (e.g., carcinoid tumors, pheochromocytoma, pancreatic NETs) | Normal: <100 ng/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Highly sensitive for neuroendocrine tumors; used for diagnosis and monitoring. |

| BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation-associated markers (ctDNA) | Breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer | Normal: Not detectable in healthy individuals Pregnancy: Not applicable |

Notes: Emerging use in liquid biopsies to detect mutations for targeted therapies. |

| KRAS mutation (ctDNA) | Colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, non-small cell lung cancer | Normal: Not detectable in healthy individuals Pregnancy: Not applicable |

Notes: Used in liquid biopsies for prognosis and guiding targeted therapy (e.g., anti-EGFR therapies). |

| HER2/neu (serum) | Breast cancer, gastric cancer | Normal: <15 ng/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Measures soluble HER2 protein; used for monitoring HER2-positive cancers. |

| Estrogen receptor (ER) / Progesterone receptor (PR) (CTCs) | Breast cancer | Normal: Not detectable in healthy individuals Pregnancy: Not applicable |

Notes: Emerging in liquid biopsies to assess hormone receptor status for treatment planning. |

| HE4 (Human Epididymis Protein 4) | Ovarian cancer | Normal: <150 pmol/L Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Often used with CA 125 for improved specificity in ovarian cancer diagnosis. |

| ProGRP (Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide) | Small cell lung cancer, neuroendocrine tumors | Normal: <50 pg/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: More specific than NSE for small cell lung cancer. |

| BRAF mutation (ctDNA) | Melanoma, colorectal cancer, papillary thyroid cancer | Normal: Not detectable in healthy individuals Pregnancy: Not applicable |

Notes: Used in liquid biopsies to guide targeted therapies (e.g., BRAF inhibitors). |

| ALK rearrangement (ctDNA) | Non-small cell lung cancer, anaplastic large cell lymphoma | Normal: Not detectable in healthy individuals Pregnancy: Not applicable |

Notes: Guides use of ALK inhibitors in targeted therapy. |

| PD-L1 expression (CTCs or serum) | Non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, bladder cancer | Normal: Varies by assay Pregnancy: Not applicable |

Notes: Emerging marker for predicting response to immunotherapy (e.g., checkpoint inhibitors). |

| Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) | Small cell lung cancer, neuroendocrine tumors | Normal: <50 pg/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Less commonly used than ProGRP but relevant in specific contexts. |

| Osteopontin | Lung cancer, mesothelioma, breast cancer | Normal: <50 ng/mL Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Investigational; may indicate tumor progression or metastasis. |

| Mesothelin | Mesothelioma, pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer | Normal: <2.5 nmol/L Pregnancy: Not significantly elevated |

Notes: Emerging marker, especially for mesothelioma diagnosis and monitoring. |

Additional Notes

- Normal Adult Levels: Values are approximate and may vary by laboratory standards or assay used. Always consult lab-specific reference ranges.

- Pregnancy Levels: Most tumor markers are not significantly elevated in pregnancy except AFP and hCG, which are naturally elevated due to fetal/placental production.

- Tumor Marker Interpretation: Markers are primarily used for monitoring treatment response, detecting recurrence, or assessing prognosis rather than primary diagnosis, except in specific cases (e.g., PSA, calcitonin). Elevated levels in non-cancerous conditions reduce specificity. The interpretation follows the AFP example with very high, moderately elevated, and slight elevation categories.

- Highlighted Markers: Markers with an asterisk (*) are the additional ones not in the original list, reflecting emerging or less commonly used markers in clinical practice.

- Emerging Markers: Liquid biopsies (e.g., ctDNA, CTCs) are increasingly used for genetic mutations (e.g., KRAS, BRAF, ALK) to guide personalized therapies.

The Future of Cancer Biomarkers

The field of oncology is constantly evolving, and the future of tumor markers is incredibly promising. New technologies are being developed to provide even more precise and timely information:

- Advanced Liquid Biopsies: Beyond just identifying single gene mutations, newer liquid biopsies can analyze patterns of DNA fragments (ctDNA), detect circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and even assess proteins and RNA, giving a comprehensive, real-time picture of the cancer.

- Proteomics and Metabolomics: These fields study the proteins and metabolic products in the body. Analyzing complex patterns of these molecules could lead to new biomarker panels that are far more sensitive and specific for early cancer detection.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): As biomarker data becomes more complex, AI and machine learning algorithms are being developed to analyze vast amounts of information. This can help identify subtle patterns that are invisible to the human eye, improving diagnostic accuracy and predicting treatment response more effectively.

How Tumor Marker Tests are Performed

- Sample Type: Most commonly blood (serum or plasma). Can also be urine, other body fluids (like CSF, pleural fluid), or tumor tissue itself (e.g., for hormone receptors, HER2, genetic mutations).

- Preparation: Usually no special preparation (like fasting) is needed for most blood-based tumor marker tests. Follow specific instructions from your doctor or the laboratory.

- Collection: Standard venipuncture (blood draw), urine collection, or biopsy procedure.

- Analysis: Performed in a clinical laboratory using various techniques, most often immunoassays (like ELISA, CLIA) that use antibodies to detect and quantify the marker.

Your Health is a Dialogue

This information is for educational purposes only and should not replace professional medical advice. Tumor marker results can be complex. Please discuss your results and any questions you have with your healthcare provider to understand what they mean for your specific situation.

Glossary of Tumor Marker Terms

- Adenocarcinoma:

- A type of cancer that forms in mucus-secreting glands throughout the body.

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP):

- An oncofetal antigen tumor marker primarily associated with liver cancer and germ cell tumors.

- ALK rearrangement (ctDNA):

- A genetic alteration (rearrangement) in the ALK gene, detected in circulating tumor DNA, which can indicate suitability for certain targeted therapies, especially in non-small cell lung cancer.

- Baseline Level:

- The initial measurement of a tumor marker level taken before treatment begins, used as a reference point to track changes over time.

- Benign:

- Not cancerous; does not spread to other parts of the body.

- Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH):

- A non-cancerous enlargement of the prostate gland.

- Beta-2 Microglobulin (B2M):

- A plasma protein tumor marker often elevated in multiple myeloma, lymphoma, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

- Biopsy:

- A medical procedure involving the removal of a small piece of tissue from the body for examination under a microscope to detect or determine the extent of a disease.

- Biomarker:

- A measurable indicator of some biological state or condition. In oncology, "cancer biomarker" is often used interchangeably with "tumor marker."

- BRAF mutation (ctDNA):

- A specific genetic change in the BRAF gene, detected in circulating tumor DNA, which can guide targeted therapies, particularly in melanoma and colorectal cancer.

- BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation (ctDNA):

- Genetic mutations in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, detected in circulating tumor DNA, associated with an increased risk of breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, and can inform treatment decisions.

- C-cell Hyperplasia:

- An increase in the number of C cells (parafollicular cells) in the thyroid, which can be a precursor to medullary thyroid cancer.

- Calcitonin:

- A hormone that functions as a tumor marker, highly specific for medullary thyroid cancer.

- Cancer Associated Antigens (CA 15-3, CA 19-9, CA 125, CA 549):

- Glycoproteins or mucins overexpressed on the surface of certain cancer cells, used as tumor markers for various cancers like breast (CA 15-3, CA 549), pancreatic/biliary (CA 19-9), and ovarian (CA 125).

- Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA):

- An oncofetal antigen tumor marker often associated with colorectal, lung, and breast cancers, though it lacks specificity.

- Checkpoint Inhibitors:

- A type of immunotherapy drug that blocks proteins (checkpoints) on immune cells or cancer cells, allowing the immune system to better recognize and attack cancer.

- Cholangiocarcinoma:

- A type of cancer that forms in the bile ducts, which are tubes that carry digestive fluid (bile) from the liver to the small intestine.

- Chromogranin A (CgA):

- A protein tumor marker highly sensitive for neuroendocrine tumors.

- Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA):

- Fragments of DNA released by cancer cells into the bloodstream, which can be analyzed to detect genetic mutations or other alterations.

- Clinical Context:

- Refers to all relevant information about a patient, including their medical history, symptoms, physical examination, and other test results, which must be considered when interpreting tumor marker levels.

- Cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1):

- A protein fragment tumor marker used primarily for non-small cell lung cancer, bladder cancer, and head and neck cancers.

- Diagnosis:

- The process of identifying the nature and cause of a disease or condition.

- Differentiated Thyroid Cancer:

- Cancers that originate from the follicular cells of the thyroid gland, such as papillary and follicular thyroid cancer.

- Ectopically:

- Refers to the production of a substance by cells or tissues where it is not normally produced (e.g., hormones produced by non-endocrine tumors).

- ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay):

- A laboratory test that uses antibodies and color change to detect and quantify a substance, such as a tumor marker.

- Endometriosis:

- A benign (non-cancerous) condition in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus.

- Estrogen Receptor (ER) / Progesterone Receptor (PR) (CTCs):

- Proteins found in circulating tumor cells (CTCs) that indicate whether a breast cancer is sensitive to estrogen or progesterone, guiding hormone therapy.

- False Negative:

- A test result that indicates a person does not have a disease or condition when they actually do.

- False Positive:

- A test result that indicates a person has a disease or condition when they actually do not.

- Fasting:

- Not eating or drinking for a certain period before a medical test.

- Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP):

- A tumor marker associated with small cell lung cancer and neuroendocrine tumors.

- Genetic Markers:

- Alterations in DNA or RNA that can be used to identify individuals at risk of disease, diagnose disease, or predict response to treatment.

- Germ Cell Tumors (GCTs):

- Cancers that begin in germ cells (reproductive cells) and can occur in the testes, ovaries, or other parts of the body.

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease:

- A group of rare tumors that form during pregnancy inside the uterus.

- Half-life:

- The time it takes for the concentration of a substance (like a tumor marker) in the body to decrease by half.

- HE4 (Human Epididymis Protein 4):

- A protein tumor marker primarily used in conjunction with CA 125 to improve specificity for ovarian cancer diagnosis and monitoring.

- Hepatitis:

- Inflammation of the liver, often caused by a viral infection.

- Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC):

- The most common type of primary liver cancer.

- HER2/neu (serum):

- A tumor marker that measures the soluble portion of the HER2 protein, used for monitoring HER2-positive breast and gastric cancers.

- Heterogeneity:

- The state of being diverse or varied. In cancer, it refers to the variation in characteristics among cancer cells within a single tumor or between different tumors in the same patient.

- Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG):

- An oncoplacental antigen tumor marker, famously known as the pregnancy hormone, but also elevated in germ cell tumors and gestational trophoblastic disease.

- Immunoassays:

- A biochemical test that measures the presence or concentration of a substance, typically using an antibody or antigen as a reactant. Examples include ELISA and CLIA.

- Immunotherapy:

- A type of cancer treatment that helps your immune system fight cancer.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease:

- Chronic inflammation of the digestive tract.

- KRAS mutation (ctDNA):

- A specific genetic change in the KRAS gene, detected in circulating tumor DNA, which can provide prognostic information and predict resistance to certain anti-EGFR targeted therapies in colorectal and pancreatic cancer.

- Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH):

- A non-specific enzyme tumor marker that can be elevated in many cancers (e.g., lymphoma, leukemia, melanoma) and non-cancerous conditions indicating tissue damage.

- Lead-Time Bias:

- An overestimation of survival duration among screening-detected cases compared to symptom-detected cases, purely because screening detects the disease earlier, not necessarily because it improves outcome.

- Liquid Biopsy:

- A non-invasive blood test that can detect cancer cells or DNA from a tumor circulating in the blood, offering an alternative to traditional tissue biopsies for monitoring and guiding treatment.

- Lymphoma:

- A type of cancer that begins in infection-fighting cells of the immune system, called lymphocytes.

- Malignant:

- Cancerous; capable of invading surrounding tissues and spreading to distant parts of the body.

- Medullary Thyroid Cancer (MTC):

- A type of thyroid cancer that develops from the C cells of the thyroid gland.

- Melanoma:

- A serious type of skin cancer that begins in cells that make pigment (melanocytes).

- Mesothelin:

- An emerging tumor marker, especially for the diagnosis and monitoring of mesothelioma, pancreatic cancer, and ovarian cancer.

- Metastasized / Generalized:

- Refers to cancer that has spread from its original site to other parts of the body.

- Mucin-like Carcinoma-Associated Antigen (MCA):

- A tumor marker primarily associated with breast cancer.

- Multiple Myeloma:

- A cancer of plasma cells, a type of white blood cell, found in the bone marrow.

- Neuroblastoma:

- A cancer that develops from immature nerve cells found in several areas of the body, most commonly in the adrenal glands.

- Neuroendocrine Tumors (NETs):

- Tumors that originate from cells that have characteristics of both nerve cells and hormone-producing (endocrine) cells.

- Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE):

- An enzyme tumor marker elevated in small cell lung cancer, neuroblastoma, and other neuroendocrine tumors.

- Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC):

- The most common type of lung cancer, accounting for about 85% of all lung cancers.

- Oncofetal Antigens:

- Proteins normally produced during fetal development but whose production is reactivated by some cancer cells in adults.

- Oncogenes:

- Genes that, when mutated or expressed at high levels, can contribute to the development of cancer.

- Oncoplacental Antigens:

- Proteins normally produced by the placenta, which can be re-expressed by certain cancer cells.

- Oncology:

- The branch of medicine that deals with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cancer.

- Osteopontin:

- An investigational tumor marker that may indicate tumor progression or metastasis in various cancers, including lung and breast.

- Pathology:

- The study of the causes and effects of diseases, especially the examination of medical specimens for diagnostic or forensic purposes.

- PD-L1 Expression (CTCs or serum):

- The presence of PD-L1 protein on circulating tumor cells (CTCs) or in serum, used as a marker to predict the potential response to immunotherapy, such as checkpoint inhibitors.

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease:

- An infection of the female reproductive organs, often leading to inflammation.

- Plasma:

- The clear, yellowish fluid portion of blood in which cells are suspended.

- Prognosis:

- The likely course or outcome of a disease; a forecast of the probable outcome of a disease.

- ProGRP (Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide):

- A tumor marker more specific than NSE for small cell lung cancer.

- Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA):

- A protein produced by cells of the prostate gland, used as a tumor marker for prostate cancer screening, diagnosis, and monitoring, though it can also be elevated in benign conditions.

- Prostatitis:

- Inflammation of the prostate gland.

- Recurrence:

- The return of cancer after a period of remission or after it has been treated.

- Renal Dysfunction:

- Impaired kidney function.

- S100 Protein:

- A tumor marker associated with melanoma, schwannomas, and some sarcomas.

- Salvage Therapy:

- Treatment given after an initial treatment has failed.

- Screening:

- Testing for a disease in people who do not have any symptoms, with the aim of early detection.

- Sensitivity (of a marker):

- The ability of a test to correctly identify individuals who have the disease (minimizing false negatives).

- Serum:

- The fluid portion of blood that remains after blood has clotted (plasma without clotting factors).

- Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC):

- A highly aggressive type of lung cancer.

- Specificity (of a marker):

- The ability of a test to correctly identify individuals who do not have the disease (minimizing false positives).

- Squamous Cell Carcinoma Antigen (SCC):

- A tumor marker used for squamous cell carcinomas, such as those of the cervix, lung, head, and neck.

- Staging:

- The process of determining the extent to which a cancer has developed or spread.

- Targeted Therapies:

- Cancer treatments that use drugs or other substances to precisely identify and attack specific cancer cells while doing less damage to normal cells.

- Thyroglobulin (Tg):

- A protein produced by the thyroid gland, used as a tumor marker to monitor for recurrence of differentiated thyroid cancer after thyroidectomy.

- Thyroidectomy:

- Surgical removal of all or part of the thyroid gland.

- Tissue Polypeptide Antigens (TPA, TPS):

- Tumor markers that measure cell proliferation and are non-specific, used in combination with other markers for various cancers.

- Tumor-Associated Antigens:

- Antigens that are frequently found on cancer cells but also on some normal cells.

- Tumor Burden:

- The total amount of cancer cells in the body.

- Tumor Markers / Cancer Biomarkers:

- Substances produced by cancer cells or by the body in response to cancer, which can be measured in blood, urine, or tissue to aid in cancer management.

- Venipuncture:

- The process of taking blood from a vein.

- Yolk Sac Tumors:

- A type of germ cell tumor, often found in the testes, ovaries, or sacrococcygeal region.

References

- National Cancer Institute (NCI). (n.d.). Tumor Markers. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/diagnosis-staging/diagnosis/tumor-markers-fact-sheet

- American Cancer Society (ACS). (2023). Tumor Markers. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/diagnosis-staging/tests/tumor-markers.html

- Mayo Clinic Staff. (n.d.). Tumor markers: Used to help diagnose cancer. Mayo Clinic Patient Care & Health Information. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/cancer/in-depth/tumor-markers/art-20045438

- Sturgeon, C. M., Hoffman, B. R., Chan, D. W., Ch'ng, S. L., Hammond, E., Hayes, D. F., ... & Diamandis, E. P. (2008). National Academy of Clinical Biochemistry laboratory medicine practice guidelines for use of tumor markers in clinical practice: quality requirements. *Clinical Chemistry*, 54(8), e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2007.094144

- Duffy, M. J. (2007). Role of tumor markers in patients with solid cancers: A critical review. *European Journal of Internal Medicine*, 18(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2006.12.001

See also

- Antiphospholipid syndrome (APS)

- Markers of autoimmune connective tissue diseases (CTDs)

- Biochemical markers of bone remodeling and diseases

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis

- Complete blood count (CBC):

- Lipoprotein(a), Lp(a)

- S100 protein tumormarker - a marker associated with brain injury

- Semen analysis (sperm count test)

- Tumor markers tests (cancer biomarkers):

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)

- ALK rearrangement (ctDNA)

- β-2 microglobulin (beta-2)

- BRAF mutation (ctDNA)

- BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation-associated markers (ctDNA)

- CA 19-9, CA 72-4, CA 50, CA 15-3 and CA 125 tumor markers (cancer antigens)

- Calcitonin

- Cancer associated antigen 549 (CA 549)

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

- Chromogranin A (CgA)

- Cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1)

- Estrogen receptor (ER) / Progesterone receptor (PR) (CTCs)

- Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP)

- HE4 (Human Epididymis Protein 4)

- HER2/neu (serum)

- Human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG)

- KRAS mutation (ctDNA)

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)

- Mesothelin

- Mucin-like carcinoma-associated antigen (MCA)

- Neuron-specific enolase (NSE)

- Osteopontin

- PD-L1 expression (CTCs or serum)

- ProGRP (Pro-gastrin-releasing peptide)

- Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test

- S100 protein tumormarker

- Squamous cell carcinoma antigen (SCC)

- Thyroglobulin (Tg)

- Tissue polypeptide antigens (ТРА, TPS)

- Urinalysis: