Breast diseases

- Understanding Breast Mastopathy (Fibrocystic Breast Changes)

- Breast Cysts

- Fibroadenoma of the Breast

- Breast Calcifications

- Intraductal Papilloma of the Mammary Gland

- Malignant Tumors (Cancer) of the Mammary Glands

- Screening and Diagnosis of Breast Diseases

- Differential Diagnosis of Breast Lumps and Symptoms

- When to Consult a Specialist

- References

Understanding Breast Mastopathy (Fibrocystic Breast Changes)

Breast mastopathy, also commonly referred to as fibrocystic breast disease or fibrocystic changes, is a benign (non-cancerous) condition characterized by lumpy, tender breast tissue. It is a very common condition, affecting many women, particularly during their reproductive years.

Symptoms and Hormonal Influence

The main symptoms of mastopathy include:

- Palpable Lumps and/or Nodules: Women may feel one or more lumps or nodular areas in their breasts, which can vary in size and shape. These areas may feel "ropy" or "cobblestone-like."

- Breast Pain or Tenderness (Mastalgia): This is a common symptom, often cyclical and worsening in the days leading up to menstruation. The lumps or nodular areas may become more prominent and painful during this premenstrual phase. With the onset of menstruation, the pain and lumpiness often subside quickly. This cyclical nature is due to the influence of hormonal changes (estrogen and progesterone) on breast tissue throughout the menstrual cycle.

- Nipple Discharge: Less frequently, mastopathy can be associated with nipple discharge. The discharge can be of a varied nature (e.g., clear, yellowish, greenish, milky). However, dark or bloody nipple discharge is a more concerning sign and may indicate a more advanced pathology or a different underlying condition, warranting prompt medical evaluation.

In many cases, these symptoms do not cause significant concern for women, and often patients may not pay special attention to them, especially if they are mild or cyclical. However, sometimes the pathological formations in breast mastopathy can be persistently painful on palpation, regardless of the menstrual cycle. The consistency of these seals can vary, and they may feel like limited, mobile formations. With more pronounced forms of mastopathy, particularly with the development of nodular mastopathy, painful sensations can radiate to the axillary (armpit) region. In such cases, even the slightest touch to the chest can become painful.

Depending on the clinical manifestations and the nature of the tissue changes, breast mastopathy is broadly classified into two main types: diffuse mastopathy and nodular mastopathy.

Diffuse Breast Mastopathy and its Types

Diffuse mastopathy involves widespread changes throughout the breast tissue. Depending on the predominant type of altered breast tissue, the following forms of diffuse mastopathy are distinguished:

- Diffuse Fibrocystic Mastopathy with Predominance of the Cystic Component: Characterized by multiple small to medium-sized cysts scattered throughout the breast tissue.

- Diffuse Fibrocystic Mastopathy with Predominance of the Fibrous Component (Fibrous Mastopathy): Marked by an increase in fibrous connective tissue, leading to firm, dense areas.

- Diffuse Fibrocystic Mastopathy with Predominance of the Glandular Component (Adenosis): Involves an increase in the number and size of breast lobules and ducts.

- Mixed Form of Diffuse Fibrocystic Mastopathy: A combination of cystic, fibrous, and glandular changes.

- Sclerosing Adenosis of the Breast: A specific type characterized by an increase in glandular elements (adenosis) along with stromal fibrosis and sclerosis, which can sometimes mimic cancer on imaging or palpation.

Nodular Breast Mastopathy

Nodular mastopathy is characterized by the presence of one or more discrete, palpable nodules or dominant lumps within the breast. These nodules are often more well-defined than the generalized lumpiness of diffuse mastopathy. While most forms of mastopathy are benign, the presence of certain types of nodular mastopathy, particularly those with atypical cellular changes (atypical hyperplasia) on biopsy, is considered a risk factor for the subsequent development of malignant breast pathology (breast cancer) in women.

Breast Cysts

Formation and Characteristics

A breast cyst is a common benign, fluid-filled sac that develops within the breast tissue, bounded by a connective tissue capsule. Breast cysts are a frequent manifestation of fibrocystic breast changes (mastopathy), occurring in both nodular and diffuse forms.

A breast cyst typically forms as a result of the dilation (expansion) of one of the breast ducts or lobules. Subsequent accumulation of fluid (secretions) within this dilated space, coupled with the formation of a fibrous capsule around it, leads to the cyst. The fluid within simple cysts is usually clear or straw-colored.

Breast cysts can vary in shape, being round, oval, or sometimes irregular. Their size can range from a few millimeters (microcysts, often not palpable) to 5 centimeters or more in diameter (giant cysts, easily palpable). On ultrasound, a typical simple breast cyst is characterized by smooth, even inner walls and an anechoic (fluid-filled) appearance.

An atypical or complex breast cyst may have internal septations, thickened walls, or intracystic growths (papillary projections) on its walls that protrude into the cyst cavity. These features may warrant further investigation (e.g., aspiration, biopsy) to rule out malignancy, although most are still benign.

Breast cysts can occur as single lesions or, more commonly, as multiple cysts (polycystic changes). In cases of polycystic mammary glands, numerous cysts of different sizes can merge and form multi-chambered clusters. As a result, the altered cystic tissue can occupy a significant portion (more than half) of the breast tissue and may lead to breast deformation or discomfort. Breast cysts are a fairly common pathology, particularly prevalent in premenopausal women, often in the age range of 35-55 years, and are less common in nulliparous women compared to those who have had children, though they can occur in any woman.

Fibroadenoma of the Breast

Nature and Clinical Features

A fibroadenoma of the breast is the most common type of benign breast tumor, composed of both fibrous (stromal) and glandular (epithelial) tissue. Fibroadenomas are considered a form of nodular mastopathy in women. Their development is often influenced by hormonal factors, particularly estrogen. Hormonal imbalances, such as those that may be present in some patients with menstrual irregularities (dysmenorrhea), can create a favorable background for the occurrence or growth of breast fibroadenomas.

Clinically, a fibroadenoma of the breast typically presents as a firm, well-defined, rounded or oval-shaped lump (knot) that is dense on palpation. When examined by a mammologist or physician, a fibroadenoma usually feels like a painless (though sometimes slightly tender), elastic or rubbery, smooth-surfaced formation. A key characteristic is its high mobility within the breast tissue; it is often described as being "slippery" or "mouse-like" as it can be easily moved around and is not attached to the overlying skin or underlying chest wall. The size of a fibroadenoma can range from very small (e.g., 0.5 cm) up to 5-7 cm in diameter, or occasionally larger (giant fibroadenoma). It is fibroadenomas that are most often self-detected as a palpable lump by young women, often those also experiencing menstrual irregularities.

While fibroadenomas are benign and do not typically increase the risk of breast cancer, any new breast lump should be evaluated by a healthcare professional to confirm the diagnosis and rule out malignancy.

Breast Calcifications

Detection and Significance

Breast calcifications are small, limited accumulations or deposits of calcium salts within the breast tissue. These are a very common finding on mammograms and are usually not palpable (cannot be felt as a lump) in the breast tissue. Mammography is highly effective at detecting and characterizing breast calcifications.

The significance of breast calcifications depends largely on their size, shape, pattern, and distribution:

- Macrocalcifications: These are larger, coarser calcifications (typically >0.5 mm). They are almost always benign and are commonly associated with aging, previous injuries, inflammation, or benign conditions like fibroadenomas or cysts. They usually do not require further investigation beyond routine screening.

- Microcalcifications: These are tiny specks of calcium, often smaller than 0.5 mm. While most microcalcifications are also benign, certain patterns of microcalcifications found during mammography can be suspicious. For example, clusters of pleomorphic (varying in shape and size), linear, or branching microcalcifications may indicate excessive activity of breast tissue cells (e.g., ductal carcinoma in situ - DCIS, an early non-invasive form of breast cancer) and are often considered by a mammologist as an early manifestation of a potentially cancerous process in a woman. Such findings typically warrant further evaluation, such as magnification views on mammography, ultrasound, or biopsy (e.g., stereotactic core biopsy).

It is important to note that the presence of calcifications does not automatically mean cancer, but specific types and patterns require careful assessment by a radiologist specializing in breast imaging.

Intraductal Papilloma of the Mammary Gland

Characteristics and Diagnosis

An intraductal papilloma is a benign (non-cancerous) tumor that grows within a milk duct of the breast. It is composed of glandular tissue along with fibrous tissue and blood vessels, forming a wart-like growth that projects into the lumen of the duct.

Key features of intraductal papillomas include:

- Size: They can range in size from a few millimeters up to several centimeters.

- Location: Most commonly located in the large milk ducts near the nipple (central papillomas), but can also occur in smaller ducts further from the nipple (peripheral papillomas).

- Occurrence: Intraductal papillomas can occur in women at any age, from puberty through to postmenopausal years, but are most common in women aged 35-55.

- Symptoms: The main and most common complaint of patients with this breast disease is nipple discharge. The discharge can vary in character:

- It may be clear, serous (straw-colored), or greenish.

- It is often bloody or blood-tinged (sanguineous or serosanguineous), which can be alarming.

- The discharge is typically spontaneous and may be from a single duct opening on the nipple.

- Number: They can be solitary (single papilloma) or multiple (papillomatosis). Multiple peripheral papillomas may carry a slightly increased risk of future breast cancer, whereas solitary central papillomas generally do not.

The most informative diagnostic method for suspected intraductal papilloma of the mammary gland is ductography (galactography). This involves cannulating the discharging duct opening on the nipple and injecting a small amount of contrast agent, followed by mammography. The contrast outlines the duct system and can reveal filling defects corresponding to the papilloma(s) within the duct lumen. Ultrasound can also be helpful in identifying intraductal masses. Biopsy (often via ductoscopy or surgical excision) is necessary to confirm the diagnosis and rule out atypia or malignancy, as some rare forms of papillary cancer can mimic benign papillomas.

Malignant Tumors (Cancer) of the Mammary Glands

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Breast cancer is a significant global health concern and one of the most common cancers affecting women. In Russia, for example, official statistics indicate that more than 34,000 new cases of breast cancer are detected annually, with an observed trend towards a decline in the age of onset among patients. The first peak in the incidence of breast cancer among women often occurs in the reproductive period, typically between the ages of 30 and 40 years. During this period, the number of cases can be around 80-100 per 100,000 women. In subsequent years of life, an increase in the incidence of breast cancer is noted; for instance, if approximately 180 cases per 100,000 women are recorded at age 50, this figure can rise to about 250 cases per 100,000 women after the age of 65.

According to projections by the World Health Organization (WHO), it was estimated that by the end of the previous century, about 750,000 women would suffer from breast cancer annually worldwide, potentially making it a leading cause of death in women aged 40 to 55 years. (Note: Current global incidence is much higher now, exceeding 2 million new cases annually).

Currently, it is generally accepted that breast cancer occurs 3-5 times more frequently against the background of pre-existing benign diseases of the mammary glands and is estimated to be 30-40 times more common in women with nodular forms of mastopathy that exhibit proliferative changes in the mammary gland epithelium (e.g., atypical hyperplasia). In this regard, it is evident that in recent years, clinical and research interest in benign breast diseases has increased significantly. Effectively managing and reducing the incidence of high-risk mastopathy is considered a real pathway to potentially reducing the overall incidence of breast cancer in women.

Heredity in Breast Cancer

Hereditary factors play a significant role in a subset of breast cancer cases. The incidence of hereditary breast cancer is estimated to be around 5-10% of all diagnosed cases. The likelihood of developing the disease increases significantly depending on the number of first-degree relatives (mother, sister, daughter) who have had breast cancer, particularly if they were diagnosed at a young age (e.g., before 40 or 50 years). Mutations in specific genes, most notably BRCA1 and BRCA2, are responsible for a large proportion of hereditary breast and ovarian cancers. Other genes like TP53, PTEN, ATM, CHEK2, PALB2, etc., also contribute to inherited predisposition.

Other Breast Cancer Risk Factors

Besides heredity, numerous other factors can increase a woman's risk of developing breast cancer:

- Age: Risk increases with age, with most breast cancers occurring in women over 50.

- Reproductive History:

- Early menarche (onset of menstruation before age 12).

- Late menopause (after age 55).

- Nulliparity (absence of childbirth) or late first full-term pregnancy (e.g., after age 30).

- Not breastfeeding or breastfeeding for a shorter duration.

- Hormonal Factors: Prolonged exposure to estrogen, such as through long-term use of combined hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or certain oral contraceptives (though the risk is complex and varies).

- Personal History of Breast Conditions: Previous diagnosis of certain benign breast diseases with atypia (e.g., atypical ductal hyperplasia, atypical lobular hyperplasia) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). A personal history of invasive breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) increases risk in the other breast or for recurrence.

- Lifestyle Factors:

- Obesity, especially after menopause.

- Lack of physical activity.

- Alcohol consumption.

- Diet (some studies suggest links with high-fat diets, though evidence is mixed).

- Radiation Exposure: High-dose radiation therapy to the chest, especially at a young age.

- Dense Breast Tissue: Women with dense breasts on mammography have a higher risk.

- Associated Medical Conditions: Certain conditions like endometriosis, uterine fibroids, hypothyroidism, or chronic autoimmune thyroiditis have been investigated for potential links, though these are not as strongly established as primary risk factors.

Common Symptoms of Breast Cancer

Early breast cancer may not cause any symptoms, which is why screening is important. When symptoms do occur, they can include:

- A New Lump or Mass: The most common symptom. A breast cancer lump is often hard, painless (though it can be tender), and has irregular edges, but it can also be soft, round, and tender.

- Swelling: Swelling of all or part of a breast (even if no distinct lump is felt).

- Skin Changes:

- Skin dimpling or puckering (retraction), sometimes resembling an orange peel (peau d'orange).

- Redness, scaling, or thickening of the skin of the breast or nipple.

- Nipple Changes:

- Nipple retraction (turning inward).

- Nipple discharge other than breast milk, especially if it is bloody, clear, or occurs from only one duct.

- Irritation, crusting, soreness, or ulceration of the skin of the nipple or areola (Paget's disease of the nipple).

- Breast or Nipple Pain: While pain is not a common early symptom of breast cancer, persistent localized pain should be evaluated.

- Deformation of the Mammary Gland: Changes in the size or shape of the breast.

- Enlargement of Axillary Lymph Nodes: Swollen lymph nodes under the arm or around the collarbone.

Screening and Diagnosis of Breast Diseases

Screening Recommendations for Suspected Breast Cancer

Regular breast screening aims to detect breast cancer at an early stage when treatment is most effective. An examination of the mammary glands by a healthcare professional is typically carried out in the first phase of the menstrual cycle (ideally days 6-12 of the cycle, when breasts are least tender and lumpy for premenopausal women).

To date, several preventive examination algorithms are recommended by Russian, European, and other international associations of mammologists and oncologists. General guidelines often include:

- Breast Self-Awareness: Women should be familiar with the normal look and feel of their breasts and report any changes to their doctor promptly.

- Clinical Breast Examination (CBE): Performed by a healthcare professional, often recommended every 1-3 years for women in their 20s and 30s, and annually for women 40 and older.

- Mammography:

- For women at average risk, screening mammography is generally recommended starting at age 40 or 50, repeated annually or biennially. Specific starting ages and intervals vary by guideline (e.g., some Russian guidelines suggested mammography once every 2 years from age 35 in the absence of specific indications for more frequent exams, and annually after 50 years). Current international guidelines often recommend starting annual or biennial screening between ages 40-50 and continuing until at least age 74-75, or as long as the woman is in good health.

- Women at high risk (e.g., strong family history, known genetic mutations like BRCA) may need to start screening earlier, include MRI, and be screened more frequently, as per their doctor's advice.

The exceptions for routine mammography are lactating or pregnant women, and adolescents, for whom mammography is prescribed only for strict indications (e.g., a suspicious palpable mass). As a rule, mammography of the mammary glands is performed in 2 projections (craniocaudal - CC, and mediolateral oblique - MLO) and, for premenopausal women, optimally scheduled during the 5th to 12th day of the menstrual cycle.

It must be remembered that the survival rate for stage I breast cancer is very high (often cited around 98-99%), which is why regular screening and early detection are so critically important.

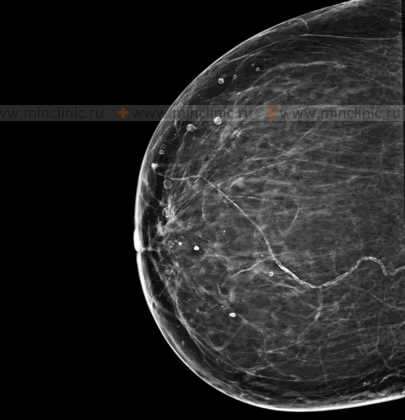

Diagnostic Methods: Mammography and Ultrasound

The main method for objectively assessing the condition of the mammary glands, particularly for screening, is X-ray examination, known as mammography. This imaging technique allows for the timely recognition of pathological changes in the mammary glands in a high percentage of cases (e.g., 95-97%). It is this quality, in contrast to some other diagnostic methods, that makes mammography the leading screening method for breast cancer. Approximately 80% of non-palpable neoplasms (cancers too small to be felt) in the mammary glands are detected during primary screening mammography.

Annual mammogram screening of the mammary glands is a crucial tool that can detect non-palpable (unable to be felt) Stage 1 breast cancer in a high percentage of women (e.g., historically cited as 93% in some cohorts), significantly improving prognosis.

The high diagnostic value of mammography and the use of modern equipment with minimum radiation doses make it possible to achieve a significant reduction in breast cancer mortality through early detection.

Ultrasound of the mammary glands is another important diagnostic tool. It is often used:

- As a supplementary examination to mammography, especially in women with dense breast tissue (where mammography may be less sensitive).

- To differentiate between cystic (fluid-filled) and solid masses found on mammography or clinical examination.

- As the primary imaging modality in younger women (e.g., under 30 or 35), pregnant or lactating women, due to the absence of ionizing radiation.

- To guide biopsy procedures (e.g., ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the breasts is a more specialized imaging technique. It is typically used:

- For screening high-risk women (e.g., those with BRCA mutations).

- To evaluate the extent of cancer after a new diagnosis.

- To assess treatment response.

- To evaluate breast implant integrity.

- When other imaging results are inconclusive.

If any suspicious findings are detected through these methods, a biopsy (e.g., fine needle aspiration, core needle biopsy, or surgical biopsy) is usually necessary to obtain tissue for histological examination and definitive diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis of Breast Lumps and Symptoms

Many breast conditions can cause lumps or other symptoms. It is crucial to differentiate benign from malignant causes:

| Condition | Common Presenting Features | Diagnostic Clues |

|---|---|---|

| Fibrocystic Changes (Mastopathy) | Lumpy, tender breasts, often cyclical pain/swelling related to menses. May have multiple small cysts or fibrous areas. | Ultrasound often shows cysts/fibroglandular tissue. Mammography may show dense tissue, cysts, benign calcifications. |

| Simple Breast Cyst | Smooth, mobile, often tender, fluid-filled lump. Size can fluctuate. | Clearly defined, anechoic on ultrasound. Can be aspirated (fluid usually clear/straw-colored). |

| Fibroadenoma | Firm, smooth, rubbery, highly mobile, well-defined lump. Common in young women. Usually painless. | Characteristic appearance on ultrasound and mammography. Biopsy confirms benign fibroepithelial lesion. |

| Intraductal Papilloma | Often presents with nipple discharge (serous or bloody), especially from a single duct. May have a small, subareolar lump. | Ductography or ultrasound can identify intraductal mass. Biopsy/excision for diagnosis. |

| Fat Necrosis | Firm lump, may have skin retraction or bruising. Often history of breast trauma or surgery. | Mammography can show oil cysts or suspicious calcifications. Biopsy may be needed to exclude malignancy. |

| Mastitis/Breast Abscess | Localized pain, redness, warmth, swelling, fever. Abscess may feel fluctuant. Often in lactating women. | Clinical diagnosis. Ultrasound can confirm abscess. Aspiration/drainage of pus for culture. |

| Breast Cancer (Malignant Tumor) | Hard, irregular, often painless lump (can be painful). Skin changes (dimpling, redness, peau d'orange), nipple retraction or discharge, axillary lymphadenopathy. | Suspicious findings on mammography/ultrasound/MRI. Biopsy is essential for diagnosis. |

| Benign Breast Calcifications | Usually no symptoms, found on mammogram. | Macrocalcifications or typically benign microcalcifications on mammography. |

| Suspicious Breast Calcifications | Usually no symptoms, found on mammogram. | Clustered, pleomorphic, linear, or branching microcalcifications on mammography. Requires further workup (magnification views, biopsy). |

When to Consult a Specialist

It is crucial for women to consult a healthcare professional (e.g., gynecologist, family doctor, breast specialist, mammologist, or oncologist) if they notice any of the following changes or symptoms:

- Any new lump or thickening in the breast or armpit.

- Changes in the size, shape, or appearance of a breast.

- Skin changes on the breast, such as dimpling, puckering, redness, scaling, or swelling.

- Nipple changes, such as retraction (turning inward), pain, redness, scaling, or discharge other than breast milk (especially if bloody or from one breast).

- Persistent breast pain that is not related to the menstrual cycle.

- Swelling or a lump in the axillary (armpit) area.

Regular screening according to recommended guidelines and prompt evaluation of any breast changes are key to early detection and successful treatment of breast diseases, including breast cancer.

References

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jul;130(1):e1-e16.

- Schnitt SJ, Collins LC. Biopsy interpretation of the breast. 3rd ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2017. (Covers pathology of mastopathy, cysts, fibroadenomas, papillomas, cancer).

- Guray M, Sahin AA. Benign breast diseases: classification, diagnosis, and management. Oncologist. 2006 May;11(5):435-49.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) for Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis. Version [Current Year]. (Refer to latest version on NCCN.org)

- World Health Organization (WHO). Breast cancer. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/breast-cancer (Refer to latest WHO information).

- American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures. [Online]. (Refer to latest version on cancer.org).

- Harvey JA, Mahoney MC, Newell MS, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Breast Pain. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016 Nov;13(11S):e31-e39.

- Lopez-Garcia MA, Geyer FC, Lacroix-Triki M, et al. Breast intraductal papillomas without atypia in core needle biopsies: correlation with findings on subsequent excision. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010 Oct;34(10):1490-7.

See also

- Abscess

- Breast diseases (mastopathy, cyst, calcifications, fibroadenoma, intraductal papilloma, cancer)

- Bursitis

- Furuncle (boil)

- Ganglion cyst

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)

- Ingrown toenail

- Lipoma (fatty tumor)

- Lymphostasis

- Paronychia, panaritium (whitlow or felon)

- Sebaceous cyst (epidermoid cyst)

- Tenosynovitis (infectious, stenosing)