Head Injury (Brain Injury)

- Facts

- Causes

- Symptoms/Signs

- Glasgow Coma Scale

- When to Seek Care

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Prognosis

- Prevention

- Head Injuries in Infants

Facts you should know about head injuries

- Traumatic brain injuries (TBI) account for thousands of deaths each year in the U.S. As well, significant numbers of people suffer temporary or permanent disability due to brain injury.

- Head injury does not necessarily mean brain injury. The bony skull protects the brain. Scalp lacerations or skull fractures may or may not have associated brain injury.

- Bleeding into and surrounding the brain usually occurs at the time of injury and over time may continue so that there is increasing pressure within the skull. However, symptoms may develop immediately or appear gradually over time.

- Medical care should be sought for any patient who is not fully awake after an injury. Activate emergency medical services or call 9-1-1.

- Computerized tomography looks for bleeding and swelling in the brain.

- Not all patients with minor head injuries require CT scanning.

- Bleeding in the brain may require neurosurgery to remove blood clots and relieve pressure on the brain.

- Not all brain injuries require neurosurgery.

- Prevention is key to avoiding head injury. The use of bicycle helmets, motorcycle helmets, and seat belts can decrease the risk of head injury.

What is a head injury?

While head injuries are one of the most common causes of death and disability in the United States, many patients with head injuries are treated and released from the emergency department after receiving treatment. Brain injury may be caused by a direct blow to the head, but shaking may also cause damage. The head is perched on the neck, and rapid acceleration or deceleration of the head can cause the brain to be damaged. The face and jaw are located in the front of the head, and brain injury may also be associated with injuries to these structures. It is also important to note that a head injury does not always mean that there is also a brain injury.

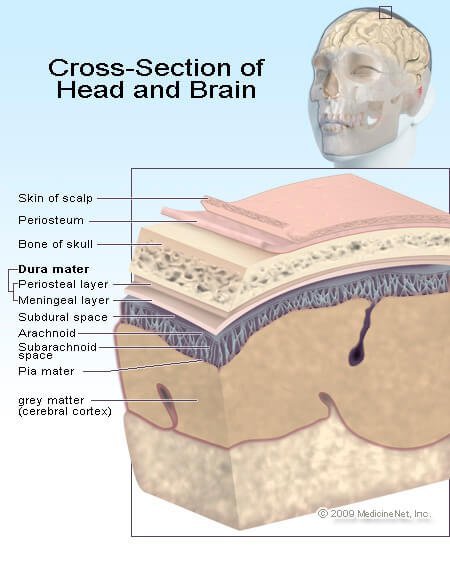

The brain is a soft and pliable structure that is almost jelly-like in feel and is surrounded by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) contained between layers of meninges, thin layers of tissue that cover the brain. There are three layers of meninges: 1) the pia mater, 2) the arachnoid mater, and 3) the dura mater. The CSF is present in the space beneath the arachnoid layer called the subarachnoid space.

The dura mater is very thick and has septae, or partitions, that help support the brain within the skull. The septae attach to the inner lining of the bones of the skull. The dura mater also helps support the large veins that return blood from the brain to the heart.

The spaces between the meninges are usually very small and compressed, but they can fill with blood when trauma occurs. This buildup of blood takes up space and increases pressure within the skull, potentially pressing into brain tissue and causing damage.

The skull protects the brain from trauma but it does not absorb much impact from a blow. Direct blows may cause fractures of the skull. There can be a contusion or bruising and bleeding to the brain tissue directly beneath the injury site. However, the brain can bounce around, or slosh, inside the skull and because of this, the brain injury may not necessarily be located directly below the trauma site. A contre-coup injury describes the situation in which the brain is damaged when the initial blow to the head causes the brain to bounce away from that forceful blow and hit the skull directly opposite the trauma site. Acceleration/deceleration and rotation are the common types of forces that can cause injuries away from the area of the skull that received the trauma.

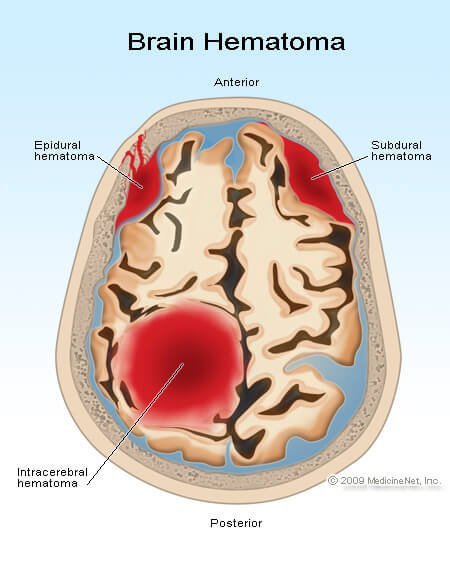

Head injuries due to bleeding are often classified by the location of the blood within the skull.

- Epidural hematoma: With an epidural hematoma, the bleeding is located between the dura mater and the skull (epi=outside). This injury most often occurs along the side of the head where the middle meningeal artery runs in a groove along the temporal bone. This bone is relatively thin and offers less protection than other parts of the skull. As the bleeding continues, the hematoma or clot expands. There is little space in the skull for the hematoma to grow and as it expands, the adjacent brain tissue is compressed. With increased pressure the brain begins to shift and becomes compressed against the bones of the skull. The pressure tends to build quickly because the septae that attach the dura to the skull bones create small spaces that trap blood. Symptoms of head injury and decreased level of consciousness occur as the pressure increases.

- Subdural hematoma: A subdural hematoma is located beneath the dura mater (sub=below), between it and the arachnoid layer. Blood in this space is able to dissipate into a larger space because there are no septae limiting the blood flow. However, after a period of time, the amount of bleeding may cause increased pressure and cause symptoms similar to those seen with an epidural hematoma.

- Subarachnoid bleed: Subarachnoid bleeding occurs in the space beneath the arachnoid layer where the cerebrospinal fluid is located. Often there is intense headache and vomiting with subarachnoid bleeding. Because this space connects with the spinal canal, pressure buildup tends not to occur. However, this injury often occurs in combination with the other types of bleeding in the brain and the symptoms may be compounded.

- Intracerebral bleed: Intracerebral bleeding occurs within the brain tissue itself. Sometimes the amount of bleeding is small, but like bruising in any other part of the body, swelling or edema may occur over a period of time, causing a progressive decrease in the level of consciousness and other symptoms of head injury.

- Sheer injury: Sometimes, the damage is due to sheer injury, where there is no obvious bleeding in the brain, but instead the nerve fibers within the brain are stretched or torn. Another term for this type of injury is diffuse axonal injury.

- Edema: All injuries to the brain may also cause swelling or edema, no different than the swelling that surrounds a bruise on an arm or leg. However, because the bones of the skull cannot stretch to accommodate the extra volume caused by swelling, the pressure increases inside the skull and causes the brain to compress against the skull.

- Skull fracture: The bones of the skull are classified as flat bones, meaning that they do not have an inside marrow. It takes a significant amount of force to break the skull, and the skull does not absorb any of that impact. It is often transmitted directly to the brain.

Skull fractures are described by which bone is broken, whether there is an associated laceration of the scalp (open fracture), and whether the bone is depressed and potentially pushed into the brain tissue.

Brain injuries often occur in combination with one another. The effects of brain injury depend upon the amount of brain tissue damaged and the level of pressure within the skull and its effects on the brain.

What are the causes of head injury?

By definition, trauma is required to cause a head injury, but that trauma does not necessarily need to be violent. Falling down a few steps or falling into a hard object may be enough to cause damage. Motor vehicle crashes account for about 17% of traumatic brain injuries, while 35% are from falls. The majority of head injuries occur in males.

Penetrating head injuries describe those situations in which the injury occurs due to a projectile, for example a bullet, or when an object is impaled though the skull into the brain.

Closed head injuries refer to injuries in which no lacerations are present.

The brain may also be injured without a direct blow to the skull. If there is trauma in which the head shakes back and forth, it may cause the brain to shake and slosh around inside the skull and become injured.

What are the symptoms of a head injury?

The symptoms of head injury can vary from almost none to loss of consciousness and coma. As well, the symptoms may not necessarily occur immediately at the time of injury. While a brain injury occurs at the time of trauma, it may take time for enough swelling or bleeding to occur to cause symptoms that are recognizable.

Initial symptoms may include a change in mental status, meaning an alteration in the wakefulness of the patient. There may be loss of consciousness, lethargy, and confusion.

Head injury symptoms may also include:

- vomiting,

- difficulty tolerating bright lights,

- leaking cerebrospinal fluid from the ear or nose,

- bleeding from the ear,

- speech difficulty,

- paralysis,

- difficulty swallowing, and

- numbness of the body.

Some of these symptoms are similar to those of a stroke. Other symptoms may be subtler and include

- nausea,

- dizziness,

- irritability,

- change in personality,

- sleep changes, including insomnia or persistent sleepiness,

- difficulty concentrating and thinking, and

- amnesia.

Late signs of significant head injury and raised pressure within the brain and skull include a dilated pupil, high blood pressure, low pulse rate, and abnormal breathing pattern. These are critical changes in the physical examination and indicate that brain death may be near.

Coma may be present if the patient doesn't awaken completely and is defined as a prolonged episode of altered level of consciousness. There are different levels of coma, and the Glasgow coma scale is one way of measuring its depth.

What is the Glasgow coma scale?

The Glasgow Coma Scale was developed to provide health care practitioners a simple way of measuring the depth of coma based upon observations of eye opening, speech, and movement. Patients in the deepest level of coma:

- do not respond with any body movement to pain,

- do not have any speech, and

- do not open their eyes.

Those in lighter comas may offer some response, to the point they may even seem awake, yet meet the criteria of coma because they do not respond normally to their environment.

| Eye Opening | |

| Spontaneous | 4 |

| To loud voice | 3 |

| To pain | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Verbal Response | |

| Oriented | 5 |

| Confused, Disoriented | 4 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Incomprehensible words | 2 |

| None | 1 |

| Motor Response | |

| Obeys commands | 6 |

| Localizes pain | 5 |

| Withdraws from pain | 4 |

| Abnormal flexion posturing | 3 |

| Extensor posturing | 2 |

| None | 1 |

An awake person has a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15, while a person who is dead would have a score of 3. The abnormal motor responses of flexion and extension describe arm and leg movement when a painful stimulus is applied. The term "decorticate" means that the cortex of the brain, the part that deals with movement, sensation, and thinking, is not working. "Decerebrate" means that the cerebrum (the whole brain), the cortex, and the brainstem that controls basic bodily functions like breathing and heartbeat, is not working.

The scale is used as part of the initial evaluation of a patient, but does not assist in making the diagnosis as to the cause of coma. Since it "scores" the level of coma, the Glasgow Coma Scale can be used as a standard method for pre-hospital emergency providers to determine the severity of head injury. It also allows the next provider in the chain of care to compare their assessment to the previous one. In this way, there is a standard score to determine whether the patient is improving or decompensating from the injury scene during the transitions to the ER, to the operating room, or ICU.

When should I contact a doctor about a head injury?

It is not normal to be unconscious or not fully awake. Emergency medical services (call 9-1-1 in your areas if it is available) should be activated for persons who have sustained an injury.

Because head injuries may also be associated with neck injuries, victims should not be moved unless they are in harm's way. If possible, it is important to wait for trained medical personnel to help with immobilizing and moving the patient.

If the patient is awake and feeling normal, it may be worthwhile seeking medical care if there was significant trauma. These patients may be considered to have a minor head injury or concussion. There is a significant amount of research that has been done to decide which people with head injuries should be admitted to the hospital for observation or have a CT (computerized tomography) scan of the head to look for bleeding.

Many guidelines exist to help a physician decide who might have a brain injury associated with a head injury. These guidelines (Ottawa or Canadian CT rules, New Orleans CT rules) apply to people ages 16 to 65 who are fully awake and have a Glasgow coma scale of 15. Potential brain injury may exist if the patient had any of the following:

- amnesia to events preceding the injury,

- vomiting,

- alcohol or drug intoxication,

- seizure,

- trauma above the collarbones,

- significant headache, and

- dangerous mechanism of injury like a fall from more than five stairs or being hit by a car.

Those older than 65 years of age are at increased risk of bleeding from head injury because the aging brain shrinks away from the skull, causing the veins that bridge from the skull to the brain surface to be more easily torn.

The rules deciding what patient might need a CT scan do not apply when the patient is taking a blood thinner or anti-platelet medication. Even minor injury may cause significant bleeding within the skull, potentially causing brain injury.

- Examples of blood thinners include warfarin (Coumadin), heparin, apixaban (Eliquis), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), and dabigatran (Pradaxa).

- Examples of anti-platelet medications include clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient), and ticagrelor (Brilinta).

How do medical professionals diagnose a head injury?

As with most injuries and illnesses, finding out what happened to the patient is very important. The health care professional will take a history of the events. The information may be provided by the patient, people who witnessed the event, emergency medical personnel, and if applicable, the police. The circumstances are very important since it is important to find out the severity and intensity of the trauma sustained by the head. Please be aware, even small head bumps or shaking can cause a brain injury.

In all trauma patients, especially those who have an injury around the collarbone, care needs to be taken to consider whether a neck or cervical spine injury has occurred. Often the neck is immobilized until this concern can be addressed.

Physical examination begins with assessing the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation) to make certain that the patient is stable and does not need emergent life-saving interventions. This is especially important in those patients who are unconscious and may not be able to maintain their own airway or breathe on their own.

If the patient is not fully awake, the examination will initially try to determine the level of coma. The Glasgow Coma Scale number is useful in tracking whether the patient is improving or declining in function over time.

If no other injuries are found on examining the body, attention will be paid to the head and the neurologic exam.

The skull may be examined for signs of trauma, including bruising (contusion) and swelling (hematoma). Palpating or feeling the skull may find evidence of a fracture. If a laceration is present, it is important to know if there is a broken bone beneath it. The face may be examined as well, since the face provides protection to the front of the head.

The health care professional may also examine the patient for evidence of a basilar skull fracture, in which an injury has occurred to the bones that support the brain. Signs of this type of fracture include:

- bruising of the tissues around the eyes (called raccoon eyes),

- bruising behind the ear (Battle's sign),

- bleeding from the ear canal, or

- cerebrospinal fluid leaking from the ear or nose.

The neurologic exam may include evaluation of the cranial nerves, the short nerves that leave the brain and control the face muscles, eye movements, swallowing, hearing, and sight, among other functions.

The exam may include evaluation of muscle tone and strength of the arms and legs; sensation in the extremities (including light touch, pain, and vibration); and if the neck is determined not to be injured, the patient's ability to walk may be assessed.

Depending upon the findings of the physical examination, a CT scan may be needed to look for bleeding in the brain.

It is important to remember that injuries to other parts of the body may also be present, and the evaluation of the head injury may occur at the same time as the evaluation of other injuries.

How is a head injury treated?

The treatment of a head injury depends upon the type of injury. For patients with minor head injuries (concussions), nothing more may be needed other than observation and symptom control. Headache may require pain medication. Nausea and vomiting may require medications to control these symptoms.

Bleeding

Intracerebral bleeding or bleeding in the spaces surrounding the brain require a neurosurgical consultation, although not all bleeding requires an operation. The decision to operate will be individualized based upon the injury and the patient's medical status.

One option may include craniotomy, drilling a hole into the skull or removing part of one of the skull bones to remove or drain a blood clot, and thereby relieve pressure on brain tissue.

Other times, the treatment is supportive, and there may be a need to monitor the pressure within the brain. The neurosurgeon may place a pressure monitor through a drilled hole through the skull to monitor the pressure. The slang term for this procedure is "placing a bolt."

Supportive care is often required for those patients with significant amounts of bleeding in their brain and who are in coma. Many times, the patient requires intubation to help control breathing and to protect them from vomiting and aspirating vomit into the lungs. Medications may be used to sedate the patient for comfort and to prevent injury if the bleeding causes combativeness. Medications may also be used to try to control swelling in the brain if necessary.

What is the prognosis for a head injury?

The goal for the treatment of any patient is to return to the level of function that they had prior to the injury. This maybe a challenge with head injury, and the return of function depends upon the severity of the injury to the brain.

How can a head injury be prevented?

Prevention is the best way to treat a head injury.

- In sporting activities, the use of a helmet may help decrease the risk of injury. Similarly, wearing a helmet while riding a motorcycle or bicycle helps minimize the risk of brain injury. Seatbelts can help prevent a head injury during a motor vehicle crash.

- Since alcohol is a risk factor for falls and other injuries, it should be used responsibly.

- Falls are a concern in the elderly. Homes can be made less fall-prone by installing assist devices on walls and in bathrooms. Loose floor coverings such as area rugs should be avoided, since walking from one floor covering to another increases the risk of falls. If needed, canes and walkers may be helpful as walking assistive devices.

What about a head injury in infants and young children?

A minor head injury in an infant is described by the American Academy of Pediatrics as the following, "A history or physical signs of blunt trauma to the scalp, skull, or brain in an infant or child who is alert or awakens to voice or light touch."

In children and infants younger than 2 years of age, it is more difficult to assess their mental status and guidelines that work for adults do not necessarily apply to this age group. The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) has developed an algorithm that helps decide when a CT scan of the head might be appropriate.

For children younger than 2 years of age:

CT scan is recommended for those patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale of less than 15, altered mental status, or a palpable skull fracture.

For those with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15 but with an occipital, temporal, or parietal hematoma (that is swelling on the back or side of the head), significant trauma, or loss of consciousness for greater than 5 seconds, or for those not acting normally according to their parents, a CT scan may be considered based upon the following:

- physician experience,

- multiple physical findings,

- worsening symptoms during observation in the ER,

- age less than 3 months, or

- parental preference.

In some situations, observation instead of CT scan may be appropriate. For all others, CT scan is not recommended.

For children older than 2 years of age:

CT scan is recommended for those patients with a Glasgow Coma Scale of less than 15, altered mental status, or a basilar skull fracture.

For patients with loss of consciousness, vomiting, severe headache, or a severe mechanism of injury, a CT scan may be considered based upon the following:

- physician experience,

- multiple physical findings,

- worsening symptoms during observation in the ER, or

- parental preference.

In some situations, observation instead of CT scan may be appropriate. For all others, CT scan is not recommended.