Torn Meniscus

- Facts

- What Is It?

- Causes

- Symptoms/Signs

- Diagnosis

- Doctor Specialists

- Treatment

- Surgery

- Recovery

- How to Prevent

Torn meniscus facts

- The medial and lateral menisci are two large C-shaped cartilages that are positioned on the top of the tibia bone at the knee.

- The knee is the largest joint in the body.

- Cartilage within the knee joint helps protect the joint from the stresses placed on it from walking, running, climbing, and bending.

- A torn meniscus occurs because of trauma caused by forceful twisting or hyper-flexing of the knee joint.

- Symptoms of a torn meniscus include knee pain, swelling, popping, and giving way.

- Treatment of a torn meniscus may include observation and physical therapy with muscle strengthening to stabilize the knee joint. When conservative measures are ineffective treatment may include surgery to repair or remove the damaged cartilage.

Introduction to the knee

The knee is the largest joint in the body. The knee allows the leg to bend where the femur (thighbone) attaches to the tibia (shinbone). The knee flexes and extends, allowing the body to perform many activities, from walking and running to climbing and squatting. There are a variety of structures that surround the knee and allow it to bend and that protect the knee joint from injury.

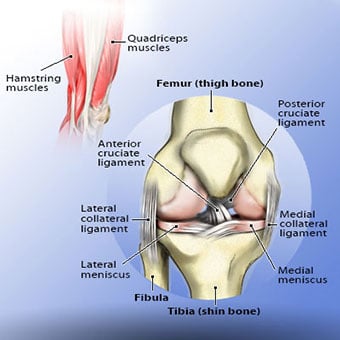

The quadriceps and hamstring muscles are responsible for moving the knee joint. When the quadriceps muscles (located on the front the thigh) contract, the knee extends or straightens. The hamstring muscles, located on the back of the thigh, are responsible for flexing or bending the knee. These muscles are also important in protecting the knee from being injured by acting to stabilize the knee and preventing it from being pushed in directions that it isn't meant to go.

There are four ligaments that also stabilize the knee joint at rest and during movement: the medical and lateral collateral ligaments (MCL, LCL) and the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (ACL, PCL).

Cartilage within the joint provides the cushioning to protect the bones from the routine stresses of walking, running, and climbing. The medial and lateral meniscus are two thicker wedge-shaped pads of cartilage attached to top of the tibia (shin bone), called the tibial plateau. Each meniscus is curved in a C-shape, with the front part of the cartilage called the anterior horn and the back part called the posterior horn.

There is also articular cartilage that lines the joint surfaces of the bones within the knee, including the tibia, femur, and kneecap (patella). The terminology torn knee cartilage refers to damage to one of the C-shaped menisci of the knee between the femur and tibia.

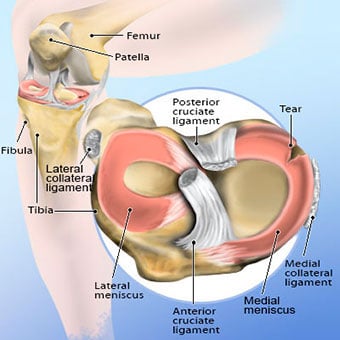

As with any injury in the body, when the meniscus is damaged, irritation occurs. If the surface that allows the bones to glide over each other in the knee joint is no longer smooth, pain can occur with each flexion or extension. The meniscus can be damaged because of a single event or it can gradually wear out because of age and overuse, causing degenerative tears.

What is a torn meniscus?

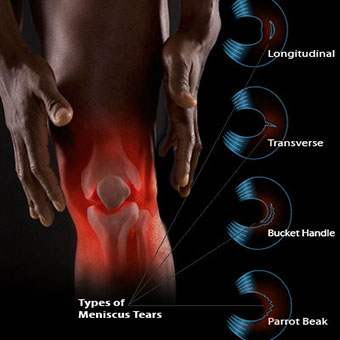

A torn meniscus is damage from a tear in the cartilage that is positioned on top of the tibia to allows the femur to glide when the knee joint moves. Tears are usually described by where they are located anatomically in the C shape and by their appearance (for example, "bucket handle" tear, longitudinal, parrot beak, and transverse). While physical examination may predict whether it is the medial or lateral meniscus that is damaged, a diagnostic procedure, like an MRI or arthroscopic surgery, can locate the specific part of the cartilage anatomy that is torn and its appearance.

Because the blood supply is different to each part of the meniscus, knowing where the tear is located may help decide how easily an injury might heal (with or without surgery). The better the blood supply, the better the potential for recovery. The outside rim of cartilage has better blood supply than the central part of the "C." Blood supply to knee cartilage also decreases with age, and up to 20% of normal blood supply is lost by age 40.

What causes a meniscus to tear?

A forceful twist or sudden stop can cause the end of the femur to grind into the top of the tibia, pinching and potentially tearing the cartilage of the meniscus. This knee injury can also occur with deep squatting or kneeling, especially when lifting a heavyweight. Meniscus tear injuries often occur during athletic activities, especially in contact sports like football and hockey. Motions that require pivoting and sudden stops, in sports like tennis, basketball, and golf, can also cause meniscus damage. The sports injury does not have to occur during a game but can also occur in practice, where the same motions lead to meniscus damage.

The risk of developing a torn meniscus increases with age because cartilage begins to gradually wear out, losing its blood supply and its resilience. Increasing body weight also puts more stress on the meniscus. Routine daily activities like walking and climbing stairs increase the potential for wear, degeneration, and tearing. It is estimated that six out of 10 patients older than 65 years have a degenerative meniscus tear. Many of these tears may never cause problems.

Because some of the fibers of the cartilage are interconnected with those of the ligaments that surround the knee, meniscus injuries may be associated with tears of the collateral and cruciate ligaments, depending upon the mechanism of injury.

While the normal cartilage is "C" or crescent-shaped, there is a variant shape that is oval or discoid. This meniscus is thicker and more prone to injury and tearing.

What are symptoms and signs of a torn meniscus?

Very often, meniscal tears do not cause symptoms or problems. However, some people with a torn meniscus know exactly when they hurt their knees. There may be the acute onset of knee pain and the patient may actually hear or feel a pop in their knee. As with any injury, there is an inflammatory response, including pain and swelling. The swelling within the knee joint from a torn meniscus usually takes a few hours to develop and depending upon the amount of pain and fluid accumulation, the knee may become difficult to move. When fluid accumulates within the enclosed area of the knee joint, it may be difficult and painful to fully extend or straighten the knee, since the knee has the most space available when it is about 15 degrees flexed.

In some situations, the amount of swelling may not necessarily be enough to notice. Sometimes, the patient isn't aware of the initial injury but starts noting symptoms that develop later. Moreover, there may not be an acute injury. The knee cartilage may become damaged as a consequence of aging, arthritis, and wearing away of the meniscus causing a degenerative meniscal tear.

After the injury, the knee joint irritation may gradually settle down and feel relatively normal as the initial inflammatory response resolves. However, other symptoms may develop over time and may include any or all of the following:

- Pain with running or walking longer distances

- Intermittent swelling of the knee joint: Many times, the knee with a torn meniscus feels "tight."

- Popping, especially when climbing up or downstairs

- Giving way or buckling (the sensation that the knee is unstable and the feeling that the knee will give way): Less commonly, the knee actually will give way and cause the patient to fall.

- Locking (a mechanical block where the knee cannot be fully extended or straightened): This occurs when a piece of torn meniscus folds on itself and blocks the full range of motion of the knee joint. The knee gets "stuck," usually flexed between 15 and 30 degrees, and cannot bend or straighten from that position.

How do doctors diagnose a meniscus tear?

The diagnosis of a knee injury begins with the history and physical examination. If there is an acute injury, the doctor will ask about the mechanism of that injury to help understand the stresses that were placed on the knee. With chronic knee complaints, the initial injury may not be remembered, but many patients who participate in athletic events or training can pinpoint the specific timing and details of the injury. Non-athletes may remember a twist or deep bend at work or doing chores around the house.

There is a true art to the physical examination of the knee. From inspecting (looking), palpating (feeling), and applying specific diagnostic maneuvers, the doctor, trainer, or physical therapist may often make the diagnosis of a torn meniscus.

Physical examination often includes palpating the joint for warmth and areas of tenderness, assessing the stability of the ligaments, and testing the range of motion of the knee joint and the power of the quadriceps and hamstring muscles. There have been many tests described to assess the internal structures of the knee. The McMurray test, named after a British orthopedic surgeon, has been used for more than 100 years to make the clinical diagnosis of a torn meniscus. The health care professional flexes the knee and rotates the tibia while feeling along the joint. The test is positive for a potential tear if a click is felt.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the test of choice to confirm the diagnosis of a torn meniscus. It is a noninvasive test that can visualize the inner structures of the knee, including the cartilage and ligaments, the surface of the bones, and the muscles and tendons that surround the knee joint. One additional benefit of the MRI before surgery is that by knowing the anatomy the orthopedic surgeon can plan a potential knee surgery and discuss alternative treatments with the patient before the operation begins.

Plain X-rays cannot be used to identify meniscal tears but may be helpful in looking for bony changes, including fractures, arthritis, and loose bony fragments within the joint. In older patients, X-rays may be taken of both knees while the patient is standing. This allows the joint spaces to be compared to assess the degree of cartilage wear. Cartilage takes up space within the joint and if the joint space is narrowed, it may be an indicator that there is less cartilage present, likely from degenerative disease. Plain X-rays may also uncover other causes of knee pain, including arthritis and pseudogout.

Prior to the widespread use of MRI, knee arthroscopy was used to confirm the diagnosis of a torn meniscus. In arthroscopy, the orthopedic surgeon inserts a small scope into the knee and looks directly at the structures within the joint. The added benefit of arthroscopy is that the injury may be repaired at the same time using additional tools that are inserted into the joint. The disadvantage of arthroscopy is that it is a surgical procedure with all the potential risks that are associated with surgery.

What types of doctors treat a torn meniscus?

The diagnosis of a torn meniscus may be made by a primary care provider with the patient is often referred to an orthopedic surgeon to either help with the diagnosis or to help with treatment decisions.

While many types of health care providers can diagnose and treat a torn meniscus, it is an orthopedic surgeon who would perform the arthroscopic surgery. For those who do not need, or choose not to have surgery, their primary care provider, the orthopedic surgeon, or a sports-medicine specialist may continue care. Often a physical therapist is involved, whether or not meniscus surgery is part of the treatment.

What is the treatment for a torn meniscus?

The treatment of a meniscus tear depends on its severity, location, and underlying disease within the knee joint. Patient circumstances also may affect the treatment options. Often it is possible to treat meniscus tears conservatively without an operation using anti-inflammatory medications and physical therapy rehabilitation to strengthen muscles around the knee to prevent joint instability. Frequently, that is all a patient needs. Patients involved in a sport or whose work is physically demanding may require immediate surgery to continue their activity. Most patients fall in between the two extremes, and the decision to use conservative treatments or proceed with an operation needs to be individualized.

Torn meniscus due to injury

The first steps in treatment after the acute injury usually include rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). This may help ease the inflammation that occurs with a torn meniscus. Anti-inflammatory medications, such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) or naproxen (Aleve), may help relieve pain and inflammation. It is important to remember that over-the-counter medications can have side effects and interactions with prescription medications. It is reasonable to ask a health care professional or pharmacist for directions as to which over-the-counter medication might be best for someone's particular situation. Rest and elevation may also require the use of crutches to limit weight-bearing.

A brace is often not used initially because most hold the knee in full extension (completely straight) and this can worsen the pain by decreasing the space within the knee joint capable of accommodating any fluid or swelling. Many patients choose initial conservative or nonsurgical treatment for a meniscus tear. Once the injury symptoms have calmed, the health care professional may recommend specifically guided exercise programs; physical therapists are especially helpful, to strengthen the muscles surrounding the knee and add to the stability of the joint. Maintaining an ideal body weight will also help lessen the forces that can stress the knee joint. Shoe orthotics may be useful to distribute the forces generated by walking and running. Braces tend not to be effective because the meniscus injury does not cause the knee joint to become structurally unstable.

If conservative therapy fails, surgery may be a consideration. Knee arthroscopy allows the orthopedic surgeon to assess the cartilage tear and potentially repair it. During an operation, the goal is to preserve as much cartilage as possible. Procedures include meniscal repair (sewing the torn edges together), partial meniscectomy (trimming away the torn area, and smoothing the injury site), or total meniscectomy, removing the whole meniscus if that is deemed appropriate.

Microfracture surgery is another surgical option to stimulate new cartilage growth. Small holes are drilled into the surface of the bone and this can stimulate articular but not meniscus cartilage development. The articular cartilage that grows as a result of surgery is not as thick or as strong as the original meniscus cartilage.

Degenerative joint disease

In older patients with the degenerative joint disease (also known as osteoarthritis) where the cartilage wears out, treatment options may be considered over a longer timetable.

Exercise and muscle strengthening may be an option to protect the joint and maintain range of motion. As well, anti-inflammatory medications may be considered to decrease swelling and pain arising from the knee joint.

Cortisone medication injections into the knee joint may be used to decrease joint inflammation and to bring temporary symptom relief that can last weeks or months. A variety of hyaluronan preparations are approved for mild to moderate knee degenerative arthritis and include Hylan G-F 20 (Synvisc), sodium hyaluronate injection (Euflexxa, Hyalgan), and hyaluronan (Orthovisc).

Other injection options are being investigated to help regrow or repair meniscus injuries. Platelet-rich plasma and stem cell injections are potential alternative treatment options to knee arthroscopy surgery, however, consensus does not yet exist that the treatments are effective. There are ongoing studies to assess whether or not they can be effective in treating knee meniscus injury instead of, or in conjunction with, arthroscopic surgery.

The use of dietary supplements, including chondroitin and glucosamine, has yet to have their effectiveness proven, but many people find relief with their use.

As a last resort, joint replacement may be an option for patients who have substantial degeneration of the knee with worn-out cartilage. These individuals typically have recurrent or constant pain and limited range of motion of the knee, preventing them from performing routine daily activities.

Can a meniscus tear heal without surgery?

Injuries that occur in parts of the cartilage that have better blood supply have a better chance to heal than those where there is little blood supply. With meniscal injuries, if the knee is stable and if the symptoms do not persist and do not limit lifestyle, nonsurgical treatments remain an option. However, the decision to defer surgery depends upon whether the knee joint remains functional and allows the patient to participate in their preferred activities.

What is rehabilitation and recovery like for a patient with a meniscus tear?

If a conservative, non-surgical approach is taken, the pain and swelling of a torn meniscus should resolve within a few days. Recovery and rehabilitation become a long-term commitment, as does making certain that the muscles surrounding the knee are kept strong to promote joint stability. Maintaining ideal body weight, and avoiding activities that cause pain are adjuncts that are often recommended.

If knee arthroscopy is performed, the rehabilitation process balances swelling and healing. The goal is to return the range of motion to the knee as soon as possible. Physical therapy is an important part of the surgery process, and most therapists work with the orthopedic surgeon to return the patient to full function as soon as possible. Since the procedure usually is planned in advance, some health care professionals advocate pre-hab. With rehabilitation prior to the procedure, the patient begins strengthening exercises for the quadriceps and hamstring muscles before surgery to prevent the routine muscle weakness that may occur immediately after an operation.

After surgery, once the swelling in the knee joint resolves, the goal of therapy is to increase the strength of the muscles surrounding the knee, return the range of motion to normal, and promote and preserve the stability of the joint.

Elite athletes return to practice within one to two weeks after surgery, but they are a motivated group of people who spend hours each day in rehabilitation. For most other patients, return to mild routine activity occurs in less than six weeks.

Most patients do well after surgery. The prognosis for return to normal activity is good but depends upon the motivation of the patient to work hard with their physical therapist and to continue that work at home after formal therapy has been completed.

What are recommended exercises once a torn meniscus has been repaired?

Rehabilitation after an operation depends upon the individual patient and the response to surgery. Specific recommendations regarding weight-bearing and exercises will be customized for the patient by the surgeon and therapist.

Usually, the goal is to return the knee to normal function within four to six weeks.

What is the prognosis of a torn meniscus? Is it possible to prevent a torn meniscus?

Most patients have their goals met by either conservative or surgical treatment, meaning that they are able to return to a normal level of function. This even includes both elite and recreational athletes who are able to return and compete in their sports.

Complications may occur during surgery. For meniscectomy, where the damaged cartilage is surgically removed, the rate of complication is less than 2%. This includes anesthetic complications, infection, and failure to prevent long-term stiffness, swelling, and recurrent pain. Other complications include deep vein thrombosis (blood clots in the leg) and the associated risks of the anesthetic. In patients who undergo meniscus repair, complications can occur in up to one-third of patients.

Once the cartilage is damaged, it cannot be repaired to be as good as the original. For that reason, prevention may actually be the best treatment for a torn meniscus. A lifelong commitment to maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding injury will decrease the stress placed on the cartilage of the knee during daily activities. Keeping muscles strong and flexible will also help protect joints. For the knee, this includes not only the quadriceps and hamstring muscles but also those in the core and back.