Zika Virus (Zika Fever)

- Zika virus facts

- What is Zika virus?

- What is the history of Zika virus outbreaks?

- What are causes and risk factors of a Zika virus infection?

- How is the Zika virus transmitted?

- What is the incubation period for a Zika virus infection?

- Is the Zika virus contagious?

- What is the contagious period for a Zika virus infection?

- What are symptoms and signs of a Zika virus infection?

- What exams and tests do health-care professionals use to diagnose a Zika virus infection?

- Can people who have returned from a country with active Zika outbreaks get tested for the infection?

- Are there home remedies for a Zika virus infection?

- What is the treatment for a Zika virus infection?

- What specialists treat Zika infections?

- What are the complications of Zika virus infections?

- What are the risks of contracting a Zika virus infection during pregnancy?

- What is the prognosis of a Zika virus infection?

- Is it possible to prevent a Zika virus infection?

- Is there a vaccine against Zika virus?

- CDC advisory on travel to areas with Zika virus, including the U.S. (Florida)

Zika virus facts

- Zika virus is a virus related to dengue, West Nile, and other viruses.

- Zika virus may play a role in developing congenital microcephaly (small head and brain) in the fetus of infected pregnant women.

- The viral disease was first noted in 1947 in Africa and has spread by outbreaks to many different countries, with an ongoing outbreak in Brazil and Puerto Rico; the first diagnosis of Zika virus in the U.S. occurred in Harris County (Houston), Texas, in January 2016.

- The virus is transmitted to most people by a mosquito (Aedes) vector; the risk factor for infection is a mosquito bite.

- The Zika virus' incubation period is about three to 12 days after the bite of an infected mosquito.

- The vast majority of infections are not contagious from person to person; however, it may be passed person to person during sex.

- The Zika virus symptoms and signs are usually

- fever,

- rash,

- joint pain, and

- conjunctivitis.

- The virus infection is usually diagnosed by the patient's history and physical exam and by blood testing (testing for the virus genome; usually done in the United States by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]).

- Treatment is related to symptom control, and over-the-counter medication is used in most infected people.

- Rarely, complications such as dehydration or neurologic problems may develop.

- In Brazil, an outbreak of Zika virus infections may be related to the development of congenital microcephaly; evidence comes from epidemiology and from Zika viruses isolated from amniotic fluid and the brain and heart of an infant with microcephaly.

- The prognosis for most Zika virus infections is good; however, complications such as microcephaly, if proven to be related to the infection in pregnancy, would be a poor outcome for the newborn. In addition, eye abnormalities, Guillain-Barré syndrome, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) may occur, with fair to poor outcomes.

- Prevention of Zika virus infections is possible if mosquito bites from infected mosquitoes are prevented.

- Currently, there is no vaccine against Zika virus infection; however, the possible link to development of microcephaly in the fetus has prompted physicians to lobby for a fast development of a vaccine.

What is Zika virus?

Zika virus (sometimes termed Zika fever) is a Flavivirus that is related to dengue, West Nile, yellow fever, and Japanese encephalitis viruses (Flaviviridae); the viruses are transmitted to humans by mosquito bites and produce a disease that lasts a few days to a week. Common symptoms include fever, rash, joint pain, and conjunctivitis (redness of the eyes). In Brazil, the viral infection has been linked to birth defects (mainly small head and small brain size, termed microcephaly) in babies (newborns) whose mothers became infected with Zika virus during their pregnancy. The CDC reported that researchers now conclude from new data published in the New England Journal of Medicine in April 2016, that Zika virus is responsible for (causes) microcephaly and other serious brain defects. According to CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden and other experts, these findings should serve as a warning to the U.S. to take Zika virus infections very seriously.

The WHO (World Health Organization) declared Zika virus infections as a public-health emergency in February 2016, after Zika virus had been reported transmitted to humans in 62 countries worldwide.

What is the history of Zika virus outbreaks?

Zika virus (ZIKV) was first isolated and identified in the Zika Forest of Uganda in 1947. Studies suggest that humans in that area of Africa could also have been infected with the virus. From 1951-1981, blood tests showed evidence of Zika virus infections in many other African countries and Indonesia (Tanzania, Egypt, Sierra Leone, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines, for example), and researchers found that transmission of the virus to humans was done by mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti). In 2007, the virus was detected in Yap Island, the first report that the virus spread outside of Africa and Indonesia to Pacific Islands. The virus has continued to spread to North, Central, and South America (Mexico, Columbia, Brazil, and into the Caribbean islands from Aruba to Jamaica). The most recent outbreaks have been noted in Puerto Rico, Cape Verde Islands, and a large ongoing outbreak is occurring in Brazil that started in May 2015 and is ongoing. The first isolation of Zika virus in the U.S. occurred in January 2016 in Harris County (Houston), Texas, from an individual who became infected in El Salvador in November and returned to Texas. Although there have not been documented mosquito transmissions in the U.S., Texas and other states have two mosquito strains (Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus) that could be capable of transmitting the viruses (see maps below). The CDC also reports 354 individuals who had locally acquired infection (acquired through mosquito bites) in the U.S. territories (Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands) and 346 travel-associated infections in the U.S. as of Apr. 6, 2016, but none due to mosquito bites in the U.S. The CDC expects these numbers to steadily increase.

For a map of the world where Zika virus infections occur, see the CDC world map at http://www.cdc.gov/zika/images/zik-world-map_12-31-2015_web.jpg.

What are causes and risk factors of a Zika virus infection?

Zika viruses are the cause of the infection. The viruses are transmitted to humans by infected vectors (Aedes mosquitoes) that also transmit other similar diseases such as dengue and Chikungunya. Theoretically, the viruses may be transmitted through blood transfusions or organ donations, although to date there are no reports of this type of transmission; there are numerous reports of Zika transmission through sexual contact.

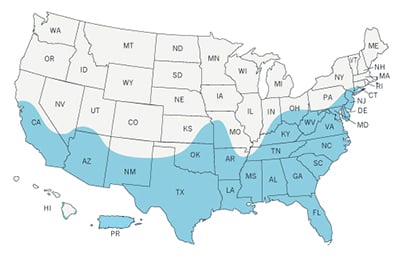

The major risk factors to get the infection are being in areas where infected mosquitoes reside, having unprotected sex with a person who has recently been diagnosed with Zika, and not taking precautions to prevent mosquito bites. The following U.S. maps provided by the CDC show where the two mosquito species that are capable of transmitting Zika viruses reside.

How is the Zika virus transmitted?

The virus is mainly transmitted by infected mosquitoes that act as vectors to infect individuals during a mosquito bite. However, the virus can be transmitted from person to person once an individual becomes infected. Investigators have evidence that transfer of Zika virus is transmitted by sexual contact more frequently than first suspected, thus providing another way the virus is transmitted. Because sexual transfer of this virus may be more frequent, physicians are recommending the use of condoms to protect uninfected sex partners from getting the disease.

Transmission could also happen in some other instances (blood transfusions, organ transplants, and from mother to fetus).

What is the incubation period for a Zika virus infection?

The incubation period for Zika viruses is about three to 12 days after the mosquito bite. Symptoms may last about four to seven days. Approximately 60%-80% of infections do not produce any symptoms or signs. The incubation period for the virus infection transmitted by sexual contact is under investigation.

Is the Zika virus contagious?

Initially in most outbreaks, the virus requires a mosquito vector to pass the virus to humans. Theoretically, donated blood and organ transplantation can allow rare person-to-person transmission. However, once a person gets a Zika infection, the virus can be contagious from that person to another person -- under certain conditions, by sexual contact. Transmission of Zika viruses to sexual contacts occurs more frequently than previously suspected; research is ongoing.

What is the contagious period for a Zika virus infection?

Zika virus can remain in semen (up to 93 days) longer than in other body fluids such as vaginal fluids, urine, or blood. The contagious period is not completely defined for Zika; however, the CDC recommends the following for individuals:

- Non-pregnant couples: If the female is diagnosed with Zika, use barrier methods (condoms) or abstinence (abstaining from sex) for at least eight weeks after illness.

- Non-pregnant couples: If the male is diagnosed with Zika, use barrier methods (condoms) or abstinence (abstaining from sex) for at least six months.

- Pregnant couples: If either partner is infected, use barrier methods (condoms) or abstinence (abstaining from sex) until the pregnancy ends.

CDC experts state that over time they expect to have more precise information about Zika infections.

What are symptoms and signs of a Zika virus infection?

Unfortunately, about 80% of all patients infected with Zika virus have little or no symptoms or signs. In many patients who develop symptoms and signs, the symptoms and signs are mild. The symptoms and signs of a Zika virus infection may include one or more the following:

- Flat or raised skin rash (may be itchy)

- Fever/chills/sweating

- Joint pains

- Conjunctivitis (red eyes)

- Muscle aches and pains

- Headache

- Less frequently, gastrointestinal discomfort with vomiting and vision problems like retro-orbital pain (pain in the back of the eye)

- Fatigue

- Appetite loss

What exams and tests do health-care professionals use to diagnose a Zika virus infection?

Health-care professionals will start diagnosis with a history and physical exam; patients should tell the provider about any recent travel to areas where the virus is active. If Zika virus infection is suspected, blood tests (done at the CDC with virus reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction tests or RT-PCR) are likely to be ordered to detect the viruses and to differentiate between similar infections such as dengue fever or Chikungunya virus infections.

Can people who have returned from a country with active Zika outbreaks get tested for the infection?

Yes, it is possible to get tested for Zika. However, the blood tests are not commonly done in many U.S. laboratories, so if your doctor agrees that you need such a test, the blood will be sent off to a specialty laboratory. The situation may change in the near future since laboratories may need to start testing for the viruses before releasing donated blood.

Are there home remedies for a Zika virus infection?

Home remedies can help reduce the symptoms of the disease and are as follows:

- Fluids to prevent dehydration

- Over-the-counter medications such as acetaminophen (Tylenol) can help reduce fever and pain

- Rest

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or other antihistamines for itching

- Avoid aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) until dengue fever can be ruled out to reduce the chance of bleeding problems (do not use aspirin to treat children).

What is the treatment for a Zika virus infection?

There is no specific medicine that can treat the viral infection; the treatment is aimed at reducing the symptoms of the disease. Oral and/or IV hydration helps reduce symptoms and dehydration. The CDC has published highly detailed guidelines about Zika infections and treatment. However, they are too detailed (for example, see references 2 [6 pages] and 3 [90 slides]) to present in this article. In addition, the CDC is likely to modify these guidelines as data emerge from new studies of this virus. Pregnant women, in addition to receiving the symptomatic treatment described above, need to discuss assessments and treatments in detail with their OB/GYN doctor; each pregnant patient may need individualized treatment during pregnancy. The CDC provides an up-to-date podcast for pregnant women concerning Zika virus (http://www2c.cdc.gov/podcasts/player.asp?f=8642324).

What specialists treat Zika infections?

Many infected people do not require treatment or can be treated by their primary-care doctor, including family medicine specialists or internists. With complications, OB/GYN doctors, maternal/fetal specialists, pediatric intensive-care specialists, and neurologists may be involved with the patient. In addition, infectious-disease specialists and travel-medicine specialists may be consulted about Zika infections.

What are the complications of Zika virus infections?

Although complications of the virus infection are rare, some can be life-threatening, such as severe dehydration. Neurological changes can occur; for example, Guillain-Barré syndrome. In addition, a large increase in congenital malformations (mainly microcephaly) and other developmental issues have been associated with these viral infections in Brazil and is currently under study. New studies suggests that eye abnormalities in microcephalic babies are linked to the virus infection (see the following section). In addition, the infection may be the cause of another brain problem, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), in which the brain cells' protective sheaths of myelin are disrupted, leading to symptoms like those of multiple sclerosis (MS).

What are the risks of contracting a Zika virus infection during pregnancy?

The risk to the mother of contracting a Zika virus infection during pregnancy is the same risk for individuals who are not pregnant, but the risk to the fetus to develop an abnormality such as microcephaly (small head and small brain) seems to be elevated in pregnancy, especially in Brazil. The epidemiological data and new research findings in Brazil suggest a likely association between congenital microcephaly and Zika infection of pregnant women. Zika virus infections first arose in Brazil in May 2015. Pregnant women, especially those in the first and early second trimester, in areas where the disease is prevalent should try to avoid any mosquito bites. Officials in Brazil are concerned since almost 4,000 babies (very unusually high number as compared to similar time periods in which only about 150 babies were diagnosed with microcephaly) have been born with microcephaly since May 2015. In addition, Dr. R. Coeli, a pediatrician in Brazil, has reported Zika viruses isolated from the amniotic fluid of two women and one infant's brain and heart tissue -- results she concludes that tie the Zika virus to microcephaly development. Officials have taken the unusual step to recommend women avoid pregnancy until the cause of the increase in microcephaly is definitively determined. Several agencies are intensively studying this problem, and a new study has data that researchers state definitively proves that Zika virus causes microcephaly (see reference 3).

In addition, a new study of infants with microcephaly and presumed Zika virus congenital infection demonstrated that 10 of 29 infants studied (34.5%) had developed a range of vision defects from minor to vision-threatening lesions (focal pigment mottling, chorioretinal atrophy, and/or optic disc abnormalities). The researchers indicate there is no definitive link yet to the eye abnormalities and the virus infection, but if other diseases are ruled out, the investigators suggest Zika virus may be is linked to the development of these vision abnormalities. In a similar small study in Brazil, two people with Zika infection developed acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) with brain cell damage to their brain's white matter.

What is the prognosis of a Zika virus infection?

For the large majority of patients who get the viral infection, the prognosis is excellent with few or no complications developing. However, depending upon the association between the infection and congenital microcephaly, eye abnormalities and Guillain-Barré syndrome being a cause-and-effect situation, the outcome of microcephaly is poor. Patients with ADEM may recover in about six months.

Is it possible to prevent a Zika virus infection?

Yes, it is possible to prevent Zika virus infections; this may be done by preventing any mosquito bites as the mosquitoes are the vector for the viral disease. In fact, some governments like those in Jamaica are encouraging residents to prevent infections by avoiding areas where mosquitoes breed, destroying areas where mosquitoes breed (for example, getting rid of old tires that contain water), wearing clothing that covers most of the skin areas of the body (long-sleeved shirts and pants), and by using mosquito repellents, such as DEET, oil of lemon eucalyptus, para-methane-diol, or permethrin (all are EPA-registered insect repellents).

Unfortunately, the two Aedes species of mosquitoes feed during the day, not only at dusk and at dawn; this increases the chances of a person getting a mosquito bite. Consequently, staying inside, removing standing water around the home, use of appropriate insect repellent, mosquito bed nets, and public-service spraying can help prevent Zika virus infections.

In addition, the CDC has recommendations for travel areas to avoid where Zika virus is present in the mosquito population (see CDC travel recommendations below).

Is there a vaccine against Zika virus?

Currently, there is no vaccine to prevent Zika virus infections. The U.S. president and health officials are requesting emergency funding ($1.9 billion) to combat the Zika virus in the U.S. to help protect pregnant women and their fetuses from the disease, to develop a vaccine and to reduce or eliminate Zika virus infections transmitted by mosquitoes. CDC officials are concerned that the problems such as neurological changes and microcephaly may be underestimated and the situation is "scarier than we initially thought," according to Dr. Anne Schuchat, deputy director at the CDC.

CDC advisory on travel to areas with Zika virus, including the U.S. (Florida)

On Jan. 15, 2016, the CDC issued a travel alert concerning Zika virus. The CDC recommended that pregnant women avoid traveling to areas with Zika outbreaks, and women thinking about becoming pregnant need to consult with their doctors before traveling to areas with Zika virus outbreaks. Women who must travel to areas with Zika virus outbreaks should consult with their doctors about pregnancy risks and take precautions to avoid any mosquito bites. The CDC is continually updating the world map of the locations where Zika virus outbreaks have and are occurring (http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/). Some athletes have chosen to skip the Olympic Games scheduled in Brazil in 2016 because of the widespread Zika outbreak in the country.

In addition, the CDC has updated recommendations for travel areas to avoid where Zika virus is present in the mosquito population so there is active transmission of the disease. This large list of countries can be found at the following site, http://www.cdc.gov/zika/geo/active-countries.html, and now includes a neighborhood named Wynwood, in Miami, Florida. About 17 individuals have been infected with the virus by mosquito bites in this area. Public-health officials are actively trying to reduce or eliminate mosquito populations in Wynwood. However, CDC officials project there will be other neighborhoods or regions in the U.S. where mosquito populations will likely become infested with the virus and become vectors for the disease.